The verbal assault that most queer children are subjected to because of their perceived distinct outer appearance changes their worldview forever. In the sense that, they not only come to realise that they are deemed a misfit in this conventionally gendered world but also make them wary of people in general, even those who may not mean harm, and both factors contributing to further alienation.

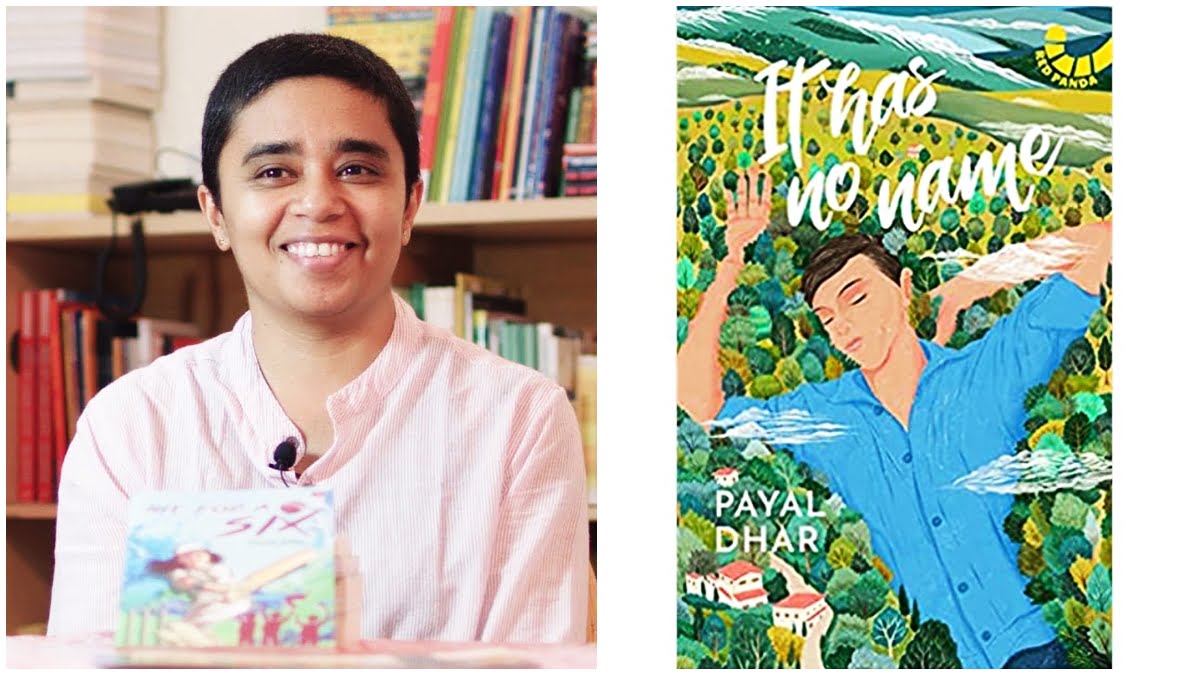

Sami, the principal character, of It Has No Name (Red Panda, an imprint of Westland, 2021) — the tenth book by journalist and novelist Payal Dhar — is one such queer teen. Her life is punctuated by gender policing by virtually everyone except her parents. The sixteen-year-old is often asked: “Are you a boy or a girl?” People are shown so confused that in a small town in the Hills Chandanisarai, where Sami and her mother had moved because her mother co-owns Bakehouse with her friend Fardeen there, a boy in a teashop comes with her order saying: “Bhaiya, your tea and bun.”

Sami, the principal character, of It Has No Name (Red Panda, an imprint of Westland, 2021) — the tenth book by journalist and novelist Payal Dhar — is one such queer teen. Her life is punctuated by gender policing by virtually everyone except her parents. The sixteen-year-old is often asked: “Are you a boy or a girl?”

Also read: Book Review: Wild Words Four Tamil Poets

Dhar’s taut prose in It Has No Name revolves around this frustration of Sami which is in turn eating her up from the inside. And to make matters worse, she had to move to a new place and leave old friends behind. Even though Chandanisarai’s weather is comforting, Sami doesn’t show her frustration to her mother. Besides the weather, being part of the sports team in her school is also a comforting sign. Not all is lost it seems.

However, Sami, who wants to just be and, as we’re told, wants to free herself from any sort of labels, feels like a lost cause. A careful reader can easily identify that, in more than three hundred pages of self-engrossed storytelling, the writer, who would have liked to make the protagonist stick to her guns, ends up demonstrating her contradicting herself.

Sample this, for example: When Sudha-didi ridicules Sami for wearing “the same boy-clothes?”, the latter retorts: “I look like myself and I’m wearing my clothes.” But in a conversation with Vidhi, the (unreliable) narrator, Sami who is ‘checking out’ Vidhi’s clothes, remarks: “Jeans with embroidery on the legs, and a very girly sweater that had ruffles around the neck.” For someone who likes wearing her clothes and without any gendered labels too at that, how come the sweater appears girly? On the contrary, it’s Vidhi who says that she ‘hates’ labels but Sami who, at least in her rants that are peppered throughout the book is irritated of gender-boxing, seems to do just the opposite.

Sami’s fickle-mindedness and being contrary to her character can be understood with an excuse: that she is a teenager going through a lot. Her parents start living separately and soon start filing for divorce. They both convince their daughter that they’re available if she ever wants to discuss ‘this’. But Sami wants her parents to ‘try harder’. It is a lot for a child to process.

But sometimes you wonder how is it that this mother, who towards the end of It Has No Name confesses that she’s ‘known it all along’ by showing to Sami Hannah Gadsby’s Netflix special, yet never had the time to have a heart-to-heart talk with her daughter about the bullying that she’s been subjected to at the hands of relatives and everyone in the society alike because of the way she conducts herself?

But sometimes you wonder how is it that this mother, who towards the end of It Has No Name confesses that she’s ‘known it all along’ by showing to Sami Hannah Gadsby’s Netflix special, yet never had the time to have a heart-to-heart talk with her daughter about the bullying that she’s been subjected to at the hands of relatives and everyone in the society alike because of the way she conducts herself?

Also read: Book Review: Fragile Monsters By Catherine Menon

Yet, not all is going wrong in Sami’s life. With the help of her crush, Jasmine, who eventually becomes her lover, and coach S. M. Swapna (SMS), Sami becomes part of their school team for a match, in which she hits herself with the bat while playing a shot and their team ends up losing the game. But because the team would’ve lost disgracefully had Sami not brought them closer to a respectable loss, everyone congratulates her.

Further, Sami saves her friend whom she might have otherwise lost to the perilous Blue Whale Challenge, and sort of, graduates from being the ‘new girl’ to the most-admired girl in the neighbourhood.

However, for a reader, there is so much that can appear overwhelming. Reading It Has No Name has been taxing for me personally. I feel that the book could have fared well had the writer concentrated on perfecting a few strands of storylines and told them well. Dhar’s usage of previously mastered themes — teenage angst and women in sports — in a new book isn’t as convincing as her erstwhile works. Not only that, for a story that premonishes harm, pain, and homophobia, there is little for the reader to do, making it a underwhelming queer read.