TJ Gnanavel’s Jai Bhim is a timely critique of the state’s authority and power against the indigenous and marginalised communities and the fundamental principles of our constitution. The film is woven around the lived experiences of the Irular tribes in Tamil Nadu’s Villupuram district and highlights the historical background of the state’s atrocities against the tribal communities. It is based on the true incident of custodial violence and murder against three members of the Irular tribe and traces the legal fight that was put up by Justice K Chandru in 1993 in Tamil Nadu.

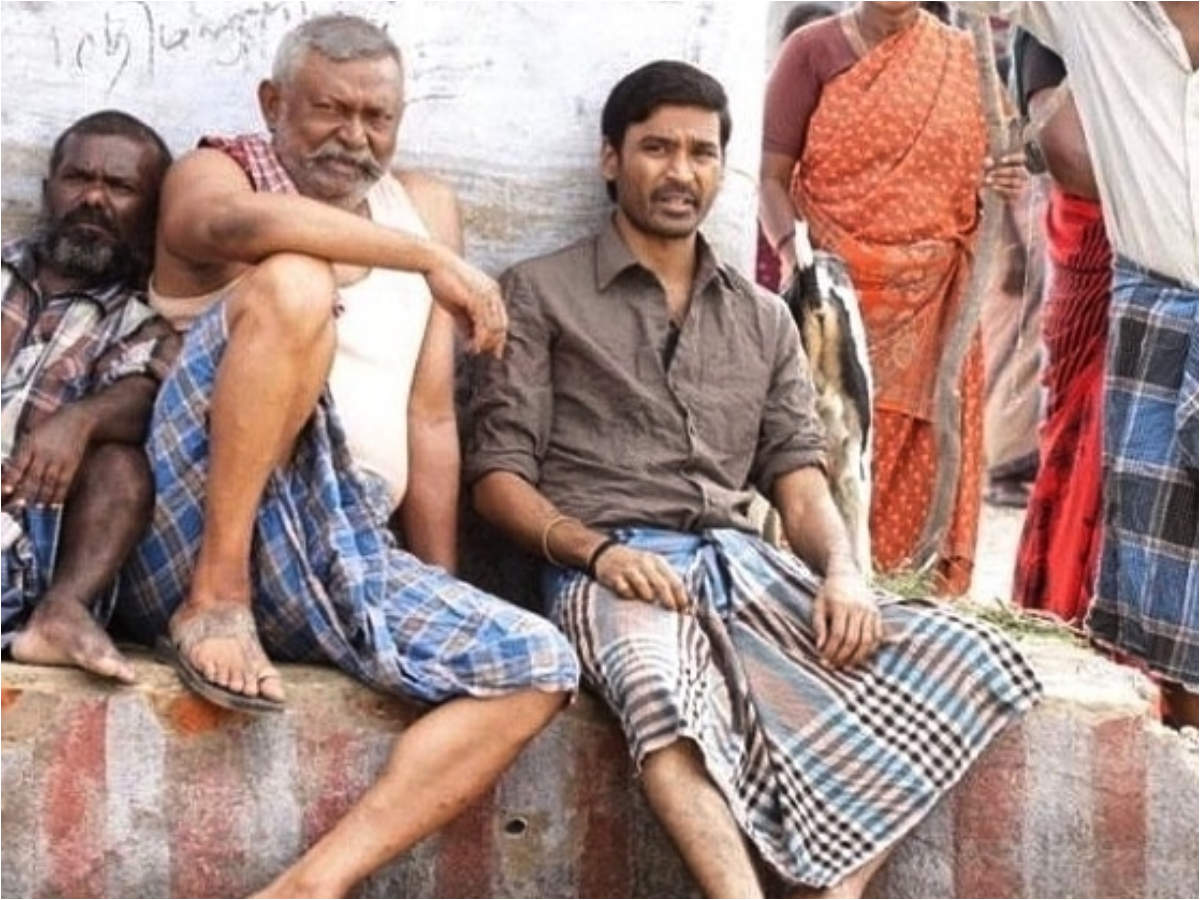

The story revolves around the lives of Sengani (Lijomol Jose) and her husband Rajakannu (Manikandan) who work as snake catchers and at times also work on the fields of landowners to secure their livelihood. After the false charge of theft, Rajakannu’s disappearance and the attempts of the police to suppress the case, Sengani approaches advocate Chandru and file a Habeas Corpus petition, thus commencing her legal fight for justice.

Also read: ‘Dalit’ As A Visual Identity: Critiquing Savarna Hypocrisy Through Film And Literature

Jai Bhim is well-executed in terms of raising the questions of the plight of marginalised community, human rights violations and state mechanism as a form of repression but falls short on certain grounds when it comes to the representation and agency of its characters.

The emerging wave of the anti-caste discourse in Tamil cinema, especially the films of directors like P.A Ranjith and Mari Selvaraj has challenged the mainstream representation of marginalised and oppressed communities. Mainstream cinema has portrayed the daily lives of marginalised communities as devoid of any joy, cultural experiences and full of misery, poverty and helplessness.

Meanwhile, Jai Bhim brings up the aspects of celebrations and joy of the lives in the community in scenes underlining cultural practices and traditional knowledge being shared with the children. Sengani and Rajakannu, both believe in a symbiotic relationship with nature. One of the scenes depicts how Rajakannu leaves the snakes in the jungle as he is aware of the fact that the killing of snakes could lead to rodent infestation in the paddy crops which can affect the overall agricultural scenario in the district.

However, these scenes also seem to be contributing to the general stereotypical representation of indigenous communities being in harmony with nature, hardly coming up as cultural assertion but rather as essential explanations of their daily lives and work.

Jai Bhim brings up the aspects of celebrations and joy of the lives in the community in scenes underlining cultural practices and traditional knowledge being shared with the children. Sengani and Rajakannu, both believe in a symbiotic relationship with nature. One of the scenes depicts how Rajakannu leaves the snakes in the jungle as he is aware of the fact that the killing of snakes could lead to rodent infestation in the paddy crops which can affect the overall agricultural scenario in the district.

However, these scenes also seem to be contributing to the general stereotypical representation of indigenous communities being in harmony with nature, hardly coming up as cultural assertion but rather as essential explanations of their daily lives and work.

Apart from this, a major part of Jai Bhim displays the extreme violence, harassment and abusive slurs that Rajakannu, Sengani and other members of their family face by the cops as a sole narrative of the marginalised community. Although we can argue about the severity of such custodial torture and administrative persecution of the community in real life, it is also difficult to ignore the fact that this agency to portray the pain and humiliation is not available to every filmmaker, especially those who are Dalit and tribals.

Rather, it is disappointing and not a surprise that the director/writers who are not from the Irular community themselves have taken such liberty in representing the atrocities against the community to build the graph of their filmography and to satisfy the urban middle-class gaze. This also contributes to the formation of savarna guilt, which is more often than not, irrelevant in how it never leads to upper-caste communities radically questioning the oppressive caste structures that they also have been complacent in upholding.

Jai Bhim seems to have taken the fight by Justice Chandru (Suriya) as a narrative of the ‘voice for the voiceless’ where the characters from the Irular community are to be saved and protected by the human rights activists and lawyers.

At the same time, Rajakannu and Sengani are also seen as exercising their agency in some ways, being assertive of their rights and dignity. The dialogue delivered by Rajakannu in the first few minutes of the film: “No matter what we do, none of us can get a land title deed, and you tell us about reading the deed?” and the image of a handprint on the brick by Sengani explores the question of their material rights such as land, housing and its relationship to identity.

Later on, Rajakannu refuses to accept the false charge of theft. He is conscious of the fact that he accepted this charge to survive and that they will never be able to break the stigma around their identity that brands them as habitual criminals.

Sengani asserts her self-respect and dignity very firmly when the senior police officer attempts to suppress the truth by luring her with money as compensation for her husband’s death. These are a few noteworthy moments that the film offers to the characters but a strong account of Sengani’s struggle for justice and her autonomous agency still goes uncaptured.

Also read: The Erasure Of Arivu: How Upper Caste Communities Continue To Invisibilise And Exploit Dalit Labour

On the other hand, the character of advocate Chandru (now Justice) is supported by various cinematic techniques. The background scores and a powerful visual backdrop with the portraits of the social thinkers and radical anti-caste revolutionaries like Babasaheb Ambedkar, Periyar, Karl Marx and Lenin project the character as another important figure of liberation and resistance. I am not suggesting that Justice Chandru was not instrumental in translating the concerns of marginalised sections, mobilizing the public, and fighting against human rights violations. In fact, in contemporary Indian democracy, where many human rights activists are being wrongfully incarcerated and are slapped with the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA) for raising their voice against state repression, Jai Bhim, also by casting a mainstream superstar like Suriya, emerges as an effective modality to garner support and empathy from the larger public.

Sengani asserts her self-respect and dignity very firmly when the senior police officer attempts to suppress the truth by luring her with money as compensation for her husband’s death. These are a few noteworthy moments that the film offers to the characters but a strong account of Sengani’s struggle for justice and her autonomous agency still goes uncaptured.

On the other hand, the character of advocate Chandru (now Justice) is supported by various cinematic techniques. The background scores and a powerful visual backdrop with the portraits of the social thinkers and radical anti-caste revolutionaries like Babasaheb Ambedkar, Periyar, Karl Marx and Lenin project the character as another important figure of liberation and resistance.

However, the romanticisation of his fight in this film tends to project him, not as a mediator who brought to the fore the struggles and rights of the marginalised sections, but as a saviour of the Irular community and thus could be seen as overshadowing the struggles and lives of the very people he fought with.

Lastly, the title Jai Bhim seems a final strike by the makers to celebrate the Ambedkarite thought that Justice Chandru believed in and perhaps, the plight of the Irular community. The glimpses of communist symbols like red flags with hammer and sickle, a commentary on the Hindi imperialism suggests a diversity of resistances but most importantly, it also frames a progressive liberal section as its true audience and has a particular niche market in mind.

As the film closes, we are shown the following quote by Justice Chandru:

“It was the writing and speeches of Dr Ambedkar that greatly helped me to understand the nature of the cases.”

Jai Bhim sure is a window onto the struggles of the Irular community, the faults in our democratic political system and raises many critical questions on the rule of law, police impunity, human rights violations, the everyday encounters of marginalised sections with the state and its machinery but majorly suffers from a saviour complex.

Featured image source: Filmibeat