Editor’s Note: FII’s #MoodOfTheMonth for November, 2021 is Popular Culture Narratives. We invite submissions on various aspects of pop culture, throughout this month. If you’d like to contribute, kindly email your articles to sukanya@feminisminindia.com

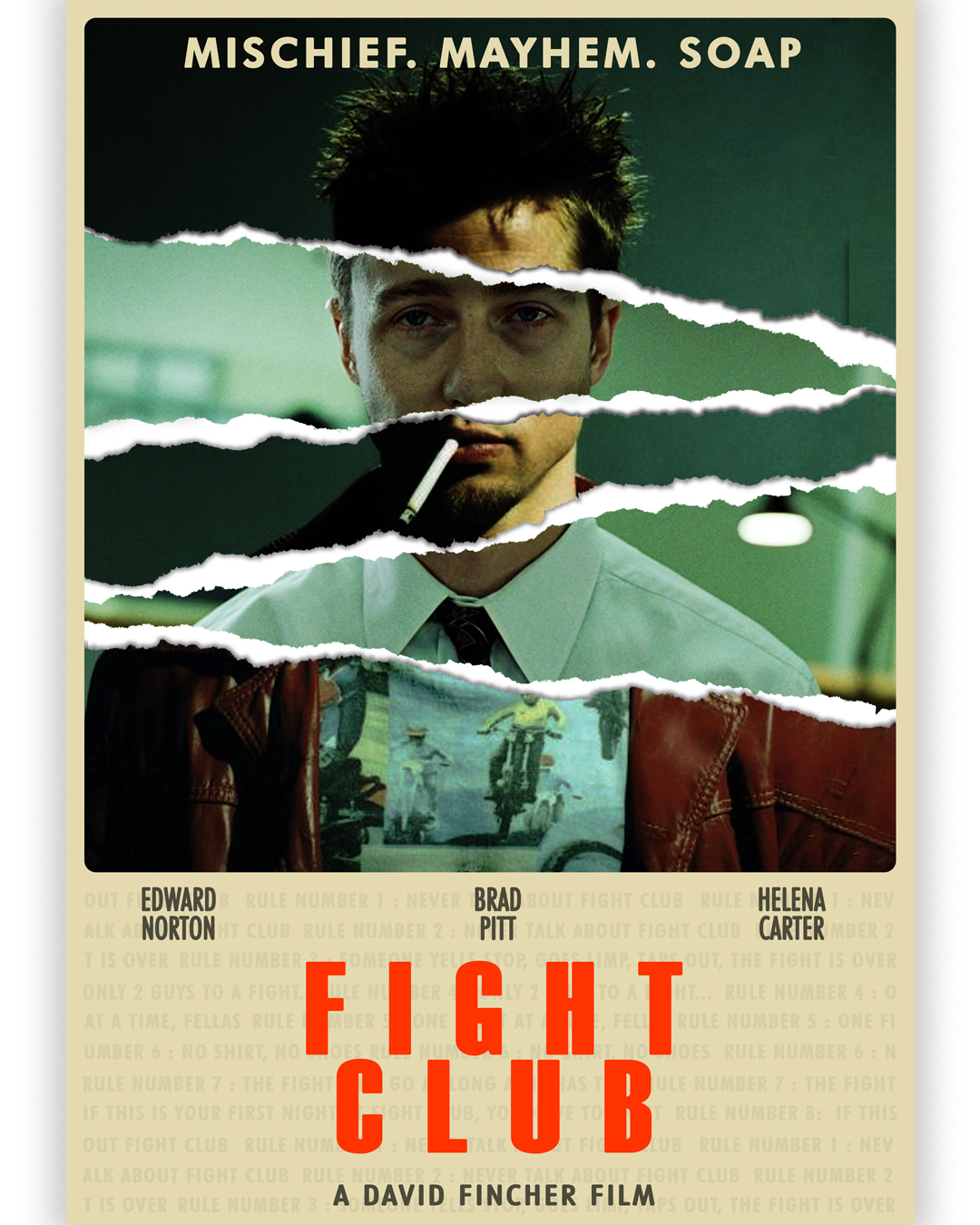

Fight Club is a famous American film which was released in 1999. Based on the novel of the same title authored by Chuck Palahniuk and directed by David Fincher, the film’s engagement with the cultural backdrop of post-war America has continued to this day owing to its gratuitous indictment of capitalist culture and its portrayal of the dangers of essentialising rebellion as ‘good’.

At its core, it is concerned with raw emotional appeal and a visceral awareness of the human body rather than a ‘constructive’ criticism of the society, and this is where a feminist analysis of the film becomes complicated. The year of the film’s release places it at the cusp of the latter half of the twentieth century, which is when feminist film theory was taking root in the United States of America.

Fight Club has endured audiences till this date for its rapid descent into violent bodily urges that are instantly recognisable no matter who watches the film, but that is also because no absolute truth is attached with these experiences – neither the man nor the woman is upheld. Robert never avenges his fellow men for mocking his feminine appearance. Marla’s agency and actual drive for death is questionable. There are valid criticisms that can be drawn from feminist film theory for this film. The presentation of masculinity and mortality in Fight Club is ultimately uncertain despite its obvious depictions – these hold a possibility of further discussion and debate for feminists off screen

As a direct outcome of feminism and women’s studies, the theory sought to examine the sociological representation of women and dominant patriarchal imagery in films. A seminal essay by Laura Mulvey entitled ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’ was published in 1975. She extrapolated that men and women are differently presented in cinematic culture. Men are usually the narrators and drivers of action in films while women become the cornerstone of the male gaze – devoid of agency and only a subject of male interest.

This is linked with voyeurism and narcissism which are taken advantage of in films to lead the audience to identify themselves with the movement of the camera and the male characters of prominence. Since then, the theory has branched to other ideas, but this central tenet remains relevant to film criticism.

Henry Giroux, a cultural critic, asserts that Fight Club film insists upon consumerism being the society’s largest problem – however, a medium as complex and multilayered as cinema can rarely be restricted to one interpretation. One must also examine the implication of masculine values in Fight Club.

It has taken decades for feminist film theory to become academically integrated in the way we understand it today, so it is not surprising to note that criticism has been levied against the theory even by women who identify as feminists themselves. From its insistence on identity politics to its reliance on Marxism and Lacanian psychoanalysis which formulate and solve problems within their own frameworks, feminist film theory has been criticised for oversimplifying and dismissing differences among women. The film Fight Club can be taken as an example of media which shows how feminist film theory can be more complex and multifaceted, as it exposes the vulnerability of male trauma and at the same time, the female character is more or less dismissed.

It is undeniable that Marla does not have a storyline independent of the male leads in Fight Club. She is also depicted as naked in the film’s sex scenes. However, the angle and momentary nature of the shots restrict her from being overly sexualised. The scenes are also central to the narrator’s later realisation that he had been unconsciously engaging in acts as Tyler, which in turn affects the entire narrative of the film.

Nevertheless, Fight Club and its fight clubs are dominated by men, both literally and metaphorically. Tyler particularly suggests that their society represses the masculine aspects of men by forcing them to focus on clothing, shopping, and physical beauty, which are supposedly more ‘feminine‘. One of the members of Fight Club, Robert or ‘Bob’, is constantly referred to and demeaned due to his ‘feminine-looking‘ chest and other body features.

For almost all of the men of Fight Club, masculinity is a physical state, satisfied by the body, unachievable in their daily lives. It is denied by principle to Marla, who nonetheless possesses a deep curiosity about death. Above all else, masculinity is problematised by the revelation of the narrator who discovers that Tyler is actually a part of himself. His emphasis on staying present inside the body is undercut and intimidated by this realisation

Some critics have maintained that the film seems to agree with the characters’ misogynist attitudes by allowing them to react to consumerism and women in a similar fashion. “Maybe another woman isn’t what I need right now”, says the narrator. The organisation of Fight Club hence emerges as an antithetical response to the reinforcement of femininity upon men; yet it is worthy to note that Tyler’s classification on the basis of gender within the film comes solely from his self-perception. Ironically, Marla seems to echo the men’s glorification of the visceral experience of death:

Narrator: When people think you’re dying, they really, really listen to you, instead of just…

Marla Singer: – instead of just waiting for their turn to speak?

She also describes at length how she would like to reach death as closely as possible without actually dying. For Tyler and the philosophy of fight clubs, the willingness to feel pain and inflict pain on others encapsulates what it feels to be a real man. Tyler burns hands, murders, and breaks buildings down. Similar to his initial assessment of womanhood, the narrator’s account of the role of consumerism is quite restricted to how he chooses to portray it – the mental images of products (inserted by editing) as well as his scathing indictment of his boss are inevitably warped into his own unreliable perspective.

Also read: Male Gaze In Visual Media: The Fetishisation Of Women And Queer Characters On Screen

Masculinity becomes even more complicated when the film’s antagonist seems to shift from that of the American culture to Tyler Durden himself. His insistence on becoming ‘real’ extends to the action of holding a cashier at gunpoint and forcing him to spell out his ‘real’ ambition of becoming a doctor. The narrator eventually believes that Tyler’s Project Mayhem is engaging in mass terrorist acts, and this suggests that the film does not exactly approve of aggression and violence as necessary against consumerism, whether they are masculine methods or not.

The narrator’s relationship and reconciliation with Marla also hint at a return to the integration of feminine values with masculine values (such as compassion with strength), and ultimately a rejection of gendered norms altogether. It is Marla who the narrator turns to when he realises he needs to stop Tyler and Project Mayhem. At the same time, Marla as a character is made to instantly forget how she felt at the hands of the conflicting behaviour of Tyler and the narrator when she holds hands with him, which is arguably unrealistic.

Whether Fight Club had a feminist objective or not is largely left to speculation for it is not clear which elements of the film are satirised and which are not. Feminist film theory cannot be used here to study Marla alone as underrepresented or masculinity alone as glorified. As Hilde Hein noted in 1990, “Some feminists advocate a new definition of theory that decenters, displaces, and foregrounds the inessential and that does not flee from experience but ‘muses at its edges’”. Therefore, any discussion about the feminism in Fight Club must be rooted in the film’s exploration of what both Marla and the male characters perpetually long for throughout the film: feeling close to death in order to evoke a second kind of life.

For almost all of the men of Fight Club, masculinity is a physical state, satisfied by the body, unachievable in their daily lives. It is denied by principle to Marla, who nonetheless possesses a deep curiosity about death. Above all else, masculinity is problematised by the revelation of the narrator who discovers that Tyler is actually a part of himself. His emphasis on staying present inside the body is undercut and intimidated by this realisation.

The form of masculinity that he had come to criticise, turns out to be a drive that he himself has repressed. With Fight Club’s tones of nihilism and absurdism and the change of mises-en-scène from bright, hopeful colours to dark, dingy lighting – it is beside the point to expect a resounding moral message from Fight Club.

By killing Tyler through himself, the narrator symbolises his final acceptance of his drive to experience death, but nowhere in the ending does he explicitly renounce his masculinity. In the beginning, violence was presented as a way to escape the consumerist world for many lost and insecure men. By the time Tyler is dead, violence becomes a socio-political tool against a tyrannical regime – but for the entire duration of the film, men have defined what those terms are supposed to mean, and while Project Mayhem’s plan succeeds, the masculine vision of asserting themselves onto the world seems to have become a strict regime by itself, egged on by a man who has doubled the world for himself.

Extending the body’s mortal ability dismisses society, harmony, and the possibility of vulnerability as strength – yet the narrator is vulnerable from the beginning to the end, he tries to be harmonious with Marla despite their constant fights, and the separation of the superficial from the real comes to haunt him when he begins to recognize himself as fragmented.

Therefore, the vision of masculinity is torn apart in Fight Club, torn away from conscious control, reduced to being an internal psychological phenomenon. The film is not interested in presenting an ideal rebellion or revolution. Marla’s character must have been distorted from the narrator’s perspective because his perception of reality is distorted. Without a singular ideal to promote, the view that Fight Club is a sexist film falls flat. It criticises what it promotes and promotes what it criticises. Its themes, motifs, and characters are all, quite literally, constantly fighting each other. Is it anti-consumerist or anti-rebellion? Anti-men or anti-feminist? The audience is left to decide.

Feminism and feminist film theory have been crucial in criticising the male gaze and the treatment of women in cinema. However, films like Fight Club demonstrate the need to politicise notions such as self-identification and masculine narcissism as products of a culture (or alternatively, mental processes) which deserve critical and academic discussion rather than being morally construed as ideal or non-ideal.

Narrative self-erasure, Marla’s defiance of the men’s expectations despite her stereotypical position, and the ‘strange time’ (in the narrator’s words themselves) during which the two collide, posit a portrait of masculinity that goes unappreciated if the film is merely studied for its representation and relative lack of female characters. Such a critical portrait could potentially be of interest to feminist scholars, for it explores an unappealing vision of masculinity without relying upon graphic sexual depictions.

Fight Club has endured audiences till this date for its rapid descent into violent bodily urges that are instantly recognisable no matter who watches the film, but that is also because no absolute truth is attached with these experiences – neither the man nor the woman is upheld. Robert never avenges his fellow men for mocking his feminine appearance. Marla’s agency and actual drive for death is questionable. There are valid criticisms that can be drawn from feminist film theory for this film. The presentation of masculinity and mortality in Fight Club is ultimately uncertain despite its obvious depictions – these hold a possibility of further discussion and debate for feminists off screen.

Also read: An Enquiry Into Internalised Male Gaze: Whose Camera Is It Anyway?

Poulomi is an undergraduate student of Literature and Journalism at Lady Shri Ram College, who can be found with coffee and also on LinkedIn