For quite some time now, both my personal as well as academic research interest revolves around the politics of gender and food. Thinking about food, which is so integral to all living beings, has amazed me, made me curious, excited, anxious, often uncomfortable and to some extent angry. The myriad of emotions that any discussion on food evokes hence needs to be articulated, further discussed and interrogated. This is particularly important as food based violence is inflicted on many marginalized, vulnerable and discriminated communities on an everyday basis. Dalits, Muslims, Women, indigenous, working class, peasants are always at the receiving end of this violence perpetuated by those privileged by caste and class.

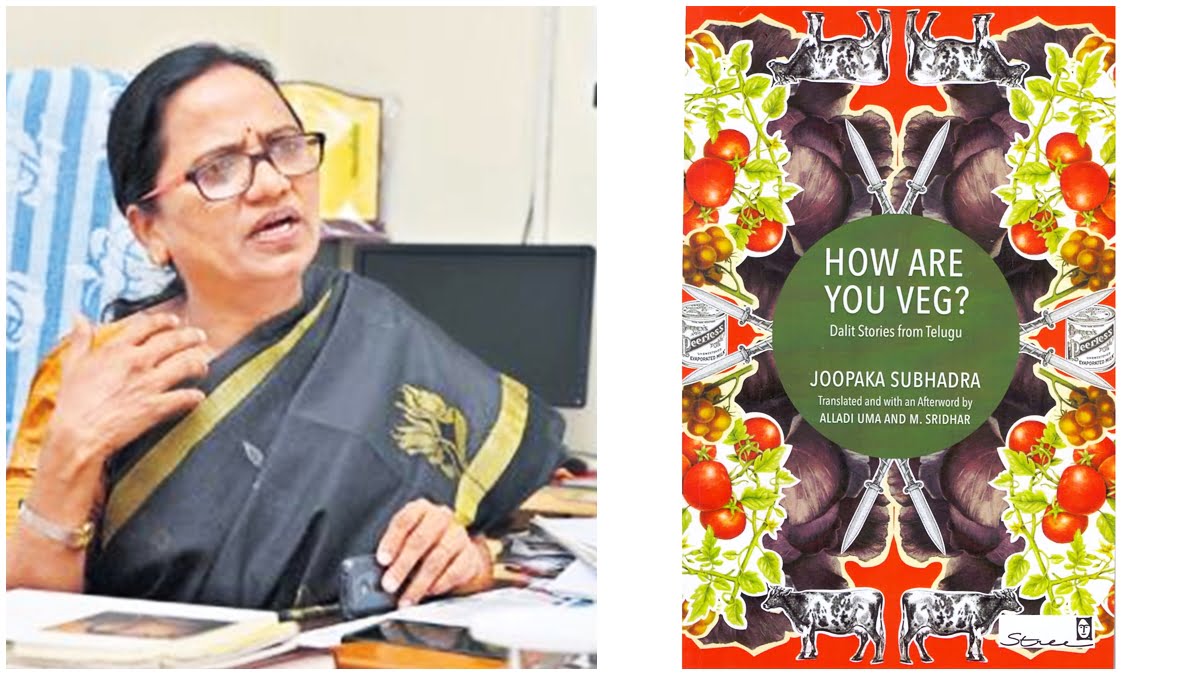

Therefore, the translation of Joopaka Subhadra’s short stories to English by Alladi Uma and M. Sridhar is a much needed treatise around the politics of food that further envelops the layers of discriminations that is omnipresent in Indian societies. In other words, it is not simply about food. The intriguing title of this collection – ‘How are you Veg?’ as well as of one of the stories, is a question that would make the readers question about their privileges and biases that are food based and much more. The 23 short stories range from highlighting the atrocities faced by people who eat beef to the lack or absence of women’s histories. Subhadra’s stories are “compelling, convining, disturbing”, as the translaters Uma and Sridhar would suggest.

The translation of Joopaka Subhadra’s short stories to English by Alladi Uma and M. Sridhar is a much needed treatise around the politics of food that further envelops the layers of discriminations that is omnipresent in Indian societies. In other words, it is not simply about food. The intriguing title of this collection – ‘How are you Veg?’ as well as of one of the stories, is a question that would make the readers question about their privileges and biases that are food based and much more.

Also read: Book Review: Wild Words Four Tamil Poets

Dalit lives and especially Dalit women’s lives have to go through some of the starkest and most inhumane treatment in the casteist system that we know. The stories by Joopaka Subhadra bring to light the lives of Madiga women, the most oppressed among Dalits in Telangana. The collection has a powerful introduction in the beginning by the author herself. It begins with her words: “Society that has progressed due to the sweat of Dalit women has sidelined our histories and literatures” (pp. xi). Hindu religious texts Bharatam, Ramayanam and Bhagavatam have “suppressed the histories, literatures, arts, and the social, cultural and legal protests of the defeated” (pp. xi).

However, Joopaka Subhadra does not confine to challenging Brahminal patriarchy in a vacuum in the book but shakes up the ideological bases and manifestations of ‘liberation’ movements such as that of Communist movements to the Dalit movements. She unflinchingly points out that none of the ‘liberation’ movements that have taken place in the ‘Telugu soil’ have given the rightful due to the Dalit women; even though they have made significant contributions to these movements. Dalit women’s writings make us re-think and question Dalit patriarchy.

While reading these stories along with the introduction and the afterword, we get a nuanced picture of the Dalit literary movement and the ‘mainstream’ feminist activism and politics. Subhadra comments: “The Dalit literary movement that questioned caste oppression and the Seemandhra women’s movement that opposed gender oppression merely continues the unutterable Hindu caste antagonism against Dalit women’s identities” (pp. xii). Joopaka Subhadra also questions the much taken-for-granted but a common attitude of pedestalising upper-caste literature as the ‘mainstream’ and literature produced by Dalits exclusively relegated as ‘Dalit’; distanced from the so-called mainstream. Dalit literature is and should be very much regarded as a part of the mainstream.

Although this collection of stories is set in the context of Telangana, it succeeds in giving out a sense of solidarity to all those who have faced violence or are survivors of appalling oppressive structures like the Indian caste system. We realise the need of such literatures emanating from the lived experiences of women who have struggled, survived and challenged; like Subhadra herself. Uma and Sridhar write: “As a Dalit writer, Joopaka Subhadra has written powerful poems and short stories that bring out the lives and conditions of the Dalits. This is what makes her stories so compelling, convincing, disturbing.” (pp. 231). Hence, it is imperative that she and her writings be known to a wider audience via the English language.

I have to point out here that the translators have done an impeccable work. For someone like me who cannot read Subhadra’s work in Telegu, going though them in English did not feel alienating. Translating with such sensitivity and honesty is still not a commonplace. Yet, both the translators achieve this rare feat. Their afterword lays out the complexities that the works of translation involve.

Also read: ‘Dalit’ As A Visual Identity: Critiquing Savarna Hypocrisy Through Film And Literature

As mentioned earlier, there are 23 extremely thought provoking stories that aligns with her own experience as a Madiga woman. In the last story of this volume – ‘Mother Bereft of Traces’ Joopaka Subhadra expresses her anguish on not being able to find her mother’s name in any of the official records in the words: “What injustice? Written histories are obliterating oral histories. Male histories are overshadowing women’s histories. Shadow histories are enveloping sunny histories.” (pp. 221) This anguish and discomfort is at the core and fuels her entire body of literature.

As mentioned earlier, there are 23 extremely thought provoking stories that aligns with her own experience as a Madiga woman. In the last story of this volume – ‘Mother Bereft of Traces’ Joopaka Subhadra expresses her anguish on not being able to find her mother’s name in any of the official records in the words: “What injustice? Written histories are obliterating oral histories. Male histories are overshadowing women’s histories. Shadow histories are enveloping sunny histories.” (pp. 221) This anguish and discomfort is at the core and fuels her entire body of literature.

The impact of her work is such that one is tempted to reveal more details about these stories. However, I am holding myself back in the hope that it will be read and re-read by a larger audience; as it is bound to have a lasting impression on the readers. We as a society continue to overlook and even dismiss the narratives about Dalit lives. Works such as that of Joopaka Subhadra’s is a noteworthy contribution in ensuring that does not continue to be the case.

Pooja Kalita has recently submitted her PhD thesis to the Department of Sociology, South Asian University (New Delhi). Her research interests include Feminism in South Asia, Sociology of Food, Urban anthropology and Politics of art and visuals in Sociology/Social Anthropology. She keeps juggling between the mediums of poetry, art, photography besides being a ‘forever student of Sociology’. You can find her on Facebook and Instagram.