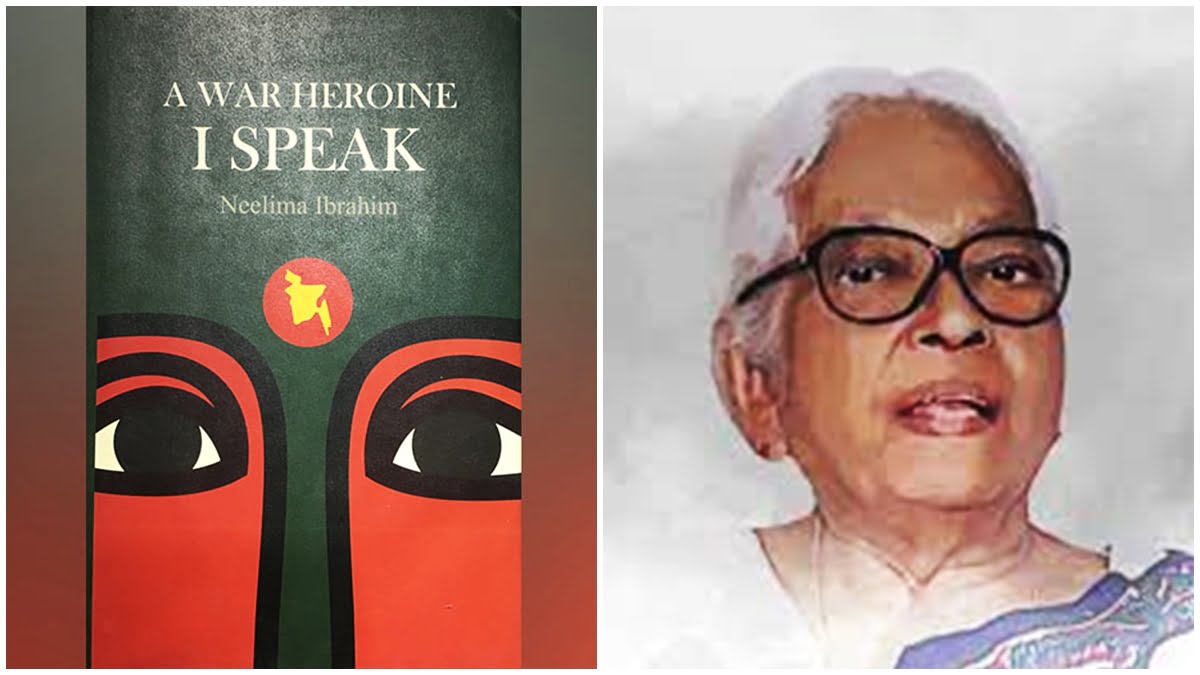

Neelima Ibrahim’s 1994-95 work Ami Birangana Bolchi, was one of the most significant attempts to highlight the impact of the 1971 war that led to the formation of Bangladesh, on women. Later on, for more reach, this Bengali piece was translated into English by Fayeza Hasanat, a Bangladeshi-American writer in 2017, and was named A War Heroine, I Speak.

One sees the book as recording of the earliest forms of evidence of showcasing how rape is systematically used as a ‘weapon of war.’ The book has seven chapters- Chapter 1 Mrs. T. Nielsen; Chapter 2 Meherjaan; Chapter 3 Rina; Chapter 4 Shefali; Chapter 5 Maina; Chapter 6 Fatema; Chapter 7 Mina.

Neelima Ibrahim’s 1994-95 work Ami Birangana Bolchi, was one of the most significant attempts to highlight the impact of war on women. Later on, for more reach, this Bengali piece was translated into English by Fayeza Hasanat, a Bangladeshi-American writer in 2017, and was named A War Heroine, I Speak.

One sees the book as recording of the earliest visible evidence of showcasing how rape is systematically used as a ‘weapon of war.’ The book has seven chapters- Chapter 1 Mrs. T. Nielsen; Chapter 2 Meherjaan; Chapter 3 Rina; Chapter 4 Shefali; Chapter 5 Maina; Chapter 6 Fatema; Chapter 7 Mina.

It says, “While men were conferred the honor of heroism, women were nothing more than objects of pity.” While talking to women and recording their narratives in the book, Ibrahim made many observations, such as how many rape victims moved to Pakistan with their perpetrators, since “home was not a place for a woman whose body was used by hundreds of men.”

Also read: Analysing Women & The Politics Of Gender In Bapsi Sidhwa’s Ice-Candy Man

The book’s first story is about Mrs. T. Nielsen/Tara Banerjee, who compares her life with mother nature in the context of tolerating everything. For her, the only way to protest is “either through taking the test of the fire like Sita or by entering the underground.” Her book emphasises on how the government even failed to recognize these women and the kind of oppression and atrocities they faced during the war. They were merely seen as “Birangonas or sinners,” as Neelima pointed out in the book. Tara, for instance, shared how even her nation’s leaders were questioning her: “Why didn’t you die, you wretched women.” Suppressed by the opposition and neglected on her own, she says, “you didn’t extend a hand to keep me alive, nor did you help me die.”

The story of Meher Jaan is that of a 14 year old girl who was raped and then had to go live with the perpetrators “only to restore a dignified identity.” Meher Jaan says, “people from my village help this animal collect us as one of their sex toys.”

In the story of Maina, she, regarding the rape camps and war, says: “Every night 3-4 soldiers would rape each of us; each would enjoy the misdeed of the soldier before him.” Maina, in the end, also with pride, claims her identity as Birangana. She says, “Today I am standing on the streets of this big city. I am a Birangana. ”

One of the stories, narrated by Rina, goes, “I would rather go to Pakistan and spend the rest of my life with these monsters. Handling these animals would be easier than confronting my loved ones.” Fatema also talked about when she was denied a job as a teacher since “characterless women could not be seated up as a role model for the schoolgirls.”

In Rina’s story, she questions how the state gave honor to martyrs and their families by naming streets after them, but no such measures are taken for Biranganas. Rina’s story raises extremely important questions about who will protect the women during the war, the failure of the state to ensure the safety of its citizens, etc. Her story highlights the role of women in myriad ways: as mothers, wives, daughters, pregnant women, etc. She says, “left behind were the pregnant wives, widowed mothers, teenage sisters, all but forgotten. The old parents lay dead now, and the wives perished with their unborn children inside their wombs. In their deaths, they became free. Many young wives and young sisters were forced to go to bed with the Pakistani army officers.”

Rina’s story is hopeful in the sense of how the readers feel the Biranganas will get at least some of the recognition that they deserve. However, she also sees it as an impossible dream. She says, “I would love to see the day when a young man or woman of this generation will come to greet me as a brave warrior, the bearer of their national flag, and the protector of their motherland. I would love to see a smile of recognition on their faces. I know it is an impossible dream because my contribution to the war and my existence as a war heroine are hidden from their knowledge. I know for sure that history has made it impossible for them to know of my existence.”

Shefali’s story, in a way, showed the double sacrifices that women made during the war. She compares her and the women’s sacrifices with that of those who died in the war. She says, “When I went to brush my teeth with my finger I found that my teeth and jaw were extremely painful. They gave their life once – but I sacrificed myself many times.” Mina sees the war and rape as misfortune, but later she is motivated by Neelima and says “You are right, Apa, please forgive me. I am a war heroine; the great leader’s words became true. I am a proud mother – a great woman. I am very happy.”

Some of the elements in the book that felt disturbing while reading A War Heroine, I Speak, was the portrayal of these women involved in the Bangladesh war of 1971. It primarily portrayed women as victims, rather than as warriors.

The invisibilisation of women’s historic contributions from the nationalist discourse is a well-known fact. In fact, in the story of nations’ struggles for independence, significant stories brought into the mainstream are of specific people, while the number of women who sacrificed for the nation were. Thus, the question of who got izzat or honor in a nationalist sense and those who got excluded is essential. Even as the book concludingly talks about women who got married, went abroad, went with their perpetrators, started some social work, and so on, it does not actually talk about how the women continued to be stigmatized. Then, it seems tokenist when the book emphasises on certain issues.

When the women in the book talk about some “kind-hearted men” who helped women build their identity, it raises the questions: Do women need help in making their identities? Does this not then go back to re-establishing the idea of who is the protector, who is the victim, and so on. And most importantly, when you talk about rebuilding their identities (rape victims), is it not limiting these women as mere rape victims with no other identities but that?

Another important point is regarding the question of active actors/agents in wartime. The whole idea of who is an active agent in nation-building and the prejudice associated with women as merely passive recipients of the fruits of war and nation building and not as active contributors to the nationalist struggle is evident in the book.

The stories of A War Heroine, I Speak are relevant in today’s context too in how the news about atrocities towards women, based on their socio-political background, remain invisibilised from the mainstreams. Another important point that the book raises is how women are seen as either good or bad. Further, in one of the stories when a Birangana says that her community didn’t even support her, one can also situate the argument of how even in contemporary public protests such as Shaheen Bagh and Kerala women’s protest of support for SC’s Sabarimala verdict, the community acts as a major hurdle in curbing women’s autonomy.

The stories of A War Heroine, I Speak are relevant in today’s context too in how the news about atrocities towards women, based on their socio-political background, remain invisibilised from the mainstreams. Another important point that the book raises is how women are seen as either good or bad. Further, in one of the stories when a Birangana says that her community didn’t even support her, one can also situate the argument of how even in contemporary public protests such as Shaheen Bagh and Kerala women’s protest of support for SC’s Sabarimala verdict, the community acts as a major hurdle in curbing women’s autonomy. The stories are so similar and relevant that makes the book timeless, even if we read it after decades it remains familiar.

References

1. Ibrahim, Nilima. “Ami birangona bolchi.” Dhaka: Jagriti Prokashoni (1998).

2. Biswas, Sanjib Kr, and Priyanka Tripathi. “History and/through Oral Narratives: Relocating Women of the 1971 War of Bangladesh in Neelima Ibrahim’s A War Heroine, I Speak.” Journal of International Women’s Studies 20.7 (2019): 154-164

3. Islam, Shereen, Kajalie. “Breaking down the Birongana: examine the (divided) media discourse on the war heroines of Bangladesh Independence movement.” International Journal of Communication (2012): 2131–2148

Great article, I used this text for my MA thesis!