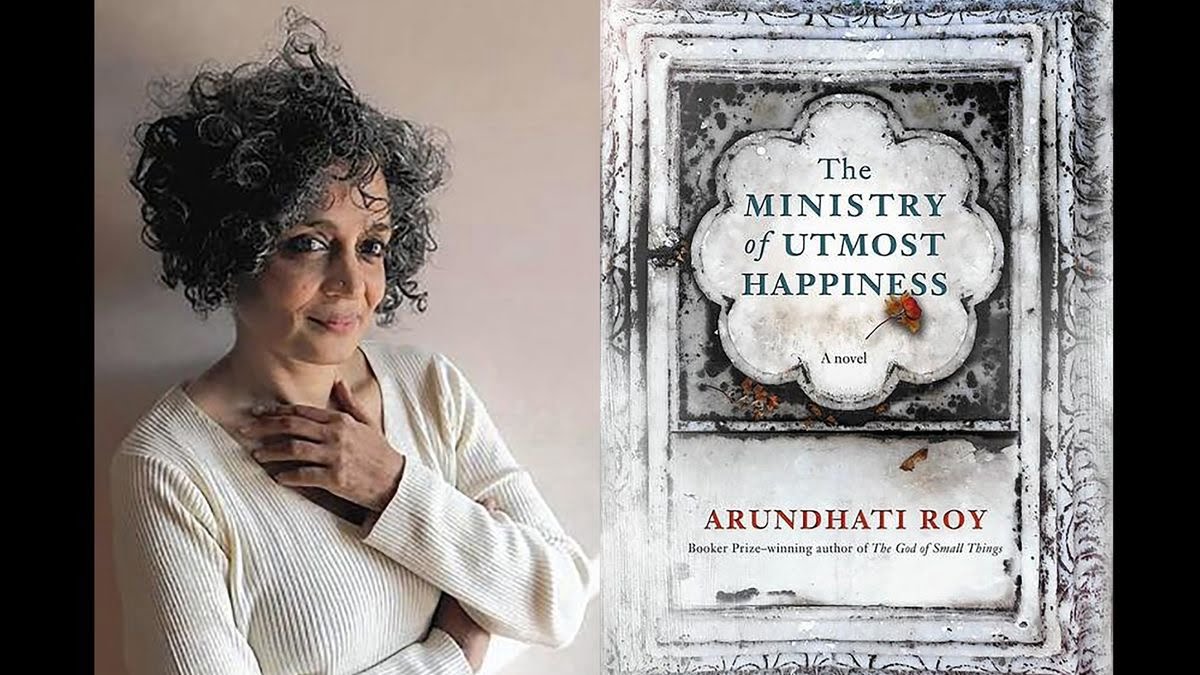

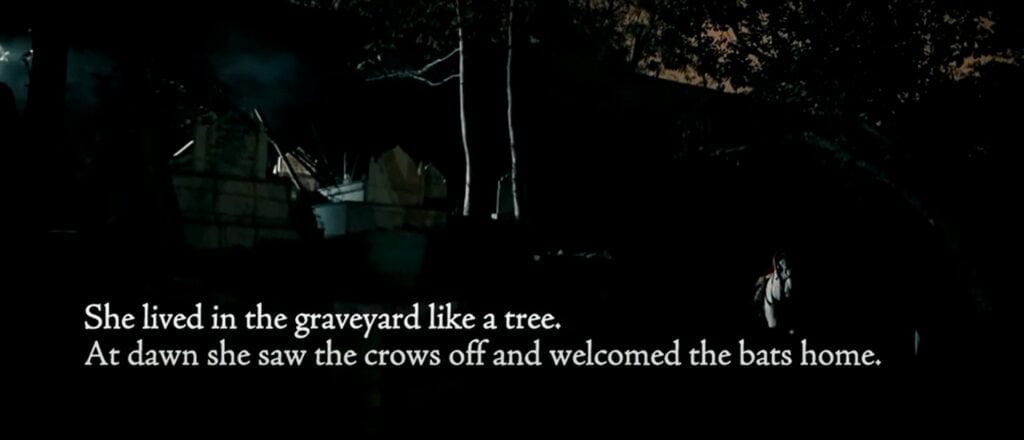

Arundhati Roy’s novel The Ministry of Utmost Happiness begins in a graveyard – a place for the dead – where the protagonist lives. Written 20 years after The God of Small Things, The Ministry of Utmost Happiness opens a universe of the marginalised, voiceless, and the disenfranchised to its readers.

Roy’s storytelling does not follow a linear pattern. It is composed of a variety of unrelated, fractured narratives, unified by one character – Anjum. These stories stem from situations of grief, abandonment, anger, helplessness, and above all, a lack of agency and subjectivity.

Roy brings the outsiders of society to the centre. This community of outsiders is populated by the prime mover of the story, Anjum, a Muslim trans woman, Saddam Hussain (Dayachand), a blind Dalit youngster, Saddam’s father, a Dalit cattle-skinner (family of chamars [untouchables] who collect cow carcasses]), Dr Azad Bhartiya, an academic-turned-activist, ‘dark-skinned’ S. Tilottama or Tilo, who is married to a journalist from a diplomatic family, and others. All of them are struggling to find their own voice and a listener.

Neoliberalism and globalisation

Gender identities, caste and class hierarchies, the ills of neoliberalism and globalisation are some of the major thematic concerns in Roy’s novel. When Anjum’s (Aftab) mother, Jahanara Begum, discovers a ‘girl-part’ in her child, she is shocked beyond belief. After three girl children, Aftab was supposed to be the ‘coveted’ boy who would carry forward the family name. Instead, the reality of begetting a Muslim “hijra” was not what Jahanara Begum was prepared for. She tries to cover up the child’s identity until it is no longer a plausible idea.

Growing up, Aftab struggles to suppress their ‘feminine’ behaviour and feels claustrophobic in a patriarchal, conservative, religious family. Gender norms and stereotypes are serious constraints for Aftab, whose identity is in a flux. In this regard, it is important to understand postmodern feminist Judith Butler’s argument on ‘performativity’ and how the confining traditional binaries perpetuate sexism.

Butler explains how sexual identities are nothing but social constructs. “Gender is a kind of persistent impersonation that passes as the real,” argues Butler, who says that gender subjectivity cannot be restricted to either ‘male’ or ‘female’. Therefore, Anjum’s gender identity is, as Butler argues, always in a “state of contextually dependent flux”. Anjum becomes a prey to derision and castigation because she does not conform to the strict gender categories of either male or female. Butler asserts, “what we take to be an internal essence of gender is manufactured through a sustained set of acts, posited through the gendered stylization of the body.”

Also read: Book Review: A War Heroine, I Speak By Neelima Ibrahim, Translated By Fayeza Hasanat

In search of acceptance

One day, Aftab follows a trans person to Khwabgah – the ‘House of Dreams’ – in search of identity, acceptance, and above all, love. Khwabgah is not located far from where Aftab was born in Old Delhi’s Shahjahanabad. In this haven, Aftab is rechristened Anjum. Soon, in the House of Dreams, Anjum realises that even though it includes others like her, the community of hijras is not homogenous. There is power dynamics in this world too, which comprises Ustad Kulsoom Bi, who is the oldest member and the head of the group; Nimmo Gorakhpuri, who is obsessed with Western fashion; and Saeeda, an educated and gender rights activist, who joins the group much later than Anjum.

Saeeda is familiar with the terms such as cis woman, trans people, queer – a language not quite known to Anjum. Saeeda is educated and is a favourite among NGOs and filmmakers because she is the archetype of an ‘unconventional’ trans person. She is the antithesis of Anjum since Saeeda represents the ‘empowered’ hijra, while Anjum is the ‘vulnerable’ one. Saeeda refuses to identify herself as the ‘victim’ of a heteronormative society. On the contrary, she comes across as an assertive individual who wants to wear her ‘trans’ identity as a badge of honour.

Anjum, on the other hand, especially after having escaped the Gujarat riots is traumatised. The incident is a turning point for Anjum – she is a Muslim trans woman who mustn’t be spared murder at the hands of Hindutva activists but she is let off because “killing hijras brings bad luck”. One of the Hindutva activists in the novel remarks, “the longer she lives, the more good luck she brings them.” So, did Anjum escape death because of her identity, which otherwise is a marker of an outcaste in mainstream society? This dilemma bothers Anjum throughout the novel and rightly so. She is unable to weigh the pros and cons of being a hijra.

Media and sensationalism

One of the important points raised by Roy is the media representation of the trans community. In trying to be the champion of their cause, the media falls prey to a narrative that harps on cruelty, abuse, and demonising histories of the transgender group. For instance, early on in the novel when Anjum finally leaves her family and is adopted by Khwabgah, she becomes media’s favourite because she is encouraged, in fact, prodded to bring out the barbarism of her family that shunned her. However, the moment Anjum decides to alter the narrative and expresses “how much her father and mother have loved her”, the journalists seem “invariably disappointed”.

Early on in the novel when Anjum finally leaves her family and is adopted by Khwabgah, she becomes media’s favourite because she is encouraged, in fact, prodded to bring out the barbarism of her family that shunned her. However, the moment Anjum decides to alter the narrative and expresses “how much her father and mother have loved her”, the journalists seem “invariably disappointed”.

In foreign newspapers, Anjum’s story is always published as “slightly altered”. This is an interesting point to reckon with. The official narrative, which is made visible to the world relies heavily on testimonies of oppression and barbarism. Michel Foucault discusses precisely this in his work on power and knowledge systems: How a particular discourse is given shape and eventually becomes the ‘official’ narrative in historical documents which are passed down to generations as the only authentic and credible version.

He argues that the subject, who is supposed to be the source of knowledge, becomes a social construct itself because a discourse will propagate and generate “certain ways of understanding” of “who we should be and what we should do”. “One has to dispense with the constituent subject, and get rid of the subject itself, that’s to say, to arrive at an analysis which can account for the constitution of the subject within a historical framework.” (Foucault 1980).

This is why, the trope of the “victimised Muslim queer people” is most sale-worthy, which can pander to readers’ appetite. Therefore, the market-driven forces of neoliberalism and globalisation play a vital role in “altering” Anjum’s story by making it a commodity to be consumed in the ‘market’ of sorrow, grief, and sob stories.

Similarly, on the other end of the spectrum, when Roy discusses the Bhopal Gas tragedy, she again brings to the centre the clash of humanity, morality, and economic gains. Roy’s incisive comment reveals the atrocity of commodification of tragedy as thus:

“In the supermarket of sorrow, the Bhopal Boy, victim of the Union Carbide gas leak remained well ahead…in the charts. The battle over the copyright of the photograph continued for years, almost as ferociously as the battle for compensation for the thousands of devastated victims of the gas leak.”

The driving force of competition in the global market and businesses is such that the politicisation of tragedies such as the Bhopal Gas incident, or the 2002 Gujarat riots, as described by Roy perpetuates a discourse which is appropriated by neoliberal ideals. Therefore, Anjum no longer occupies the “Number One spot in the media” because she has been usurped by the ‘Bhopal Boy’ and does not make for a clickbait headline. This shows the attitude of the Western media and sensational journalism which governs the consumption behaviour within a ‘free market’ culture.

Taking forward the debate of privatisation and globalisation, Sylvia Walby in Globalization and Inequalities raises a pertinent argument about how it is necessary to integrate social democracy in the narrative of neoliberalism without which there will be inequality.

She asserts, “Economic development and economic growth are central to the neoliberal project. The achievement of economic development is used as the justification of other less popular aspects of neoliberalism such as inequality” . In Roy’s novel too, we see the stark division in terms of how the working class is treated in the name of development. Saddam Hussain (Dayachand) recounts how he turned blind while guarding a steel art installation during peak summer months at an art gallery.

Also read: Analysing Women & The Politics Of Gender In Bapsi Sidhwa’s Ice-Candy Man

The marginalised is considered dispensable. Anjum remarks, “This place where we live (the graveyard), where we have made our home, is the place of falling people… even we aren’t real. We don’t really exist.” On the one hand, there is a new chapter being written about rising and shining India where “…Bombay is our New York, Delhi is our Washington and Kashmir is our Switzerland”. On the other hand, “the Santhal tribes from Hazaribagh, displaced by East Parej coal mines, (the) Union Carbide Gas victims,” as recounted by Dr Azad Bhartiya, are kept away from the ‘neoliberal project’ of welfare and development.

Initially, Roy describes this shift by recounting the displacement of the most trusted brand of sherbet called Rooh Afza by Coca Cola. Rooh Afza, meant to be a healthy tonic to beat the summer heat had become a household name and had ruled the market for 40 years, “But eventually, the Elixir of the Soul that had survived wars and the bloody birth of three countries, was, like most things in the world, trumped by Coca-Cola.” Through this statement, Roy offers a sharp critique of neoliberal capitalism and globalisation.

Initially, Roy describes this shift by recounting the displacement of the most trusted brand of sherbet called Rooh Afza by Coca Cola. Rooh Afza, meant to be a healthy tonic to beat the summer heat had become a household name and had ruled the market for 40 years, “But eventually, the Elixir of the Soul that had survived wars and the bloody birth of three countries, was, like most things in the world, trumped by Coca-Cola.” Through this statement, Roy offers a sharp critique of neoliberal capitalism and globalisation.

In her space in the graveyard, which Anjum eventually turns into the Jannat Guest House and later extends it to Jannat Funeral Services, those who have been discarded by society find the vestiges of dignity, shelter, anonymity, and a sense of freedom. The graveyard becomes a leveller which is situated between the two opposing worlds of the haves and the have-nots. Here, everyone is equal.

Taming Medusa

However, they are also considered a major threat to the vision of a neoliberal state. As Dr Shyaonti Talwar explains, “The underbelly of Delhi, the invisible spaces Roy courses through, is no less or better than Medusa’s head with the expendable, writhing and crawling, serpentine beings with serpentine thoughts and tendencies and conflicts which these spaces shelter, harbour and produce, which are a menace to the 21st century image of the nation state.”

Here, the metaphor of Medusa used by Roy must be noted. Though she is a goddess in Greek mythology, she is also transgressive, who must be tamed and contained. Just like the hydra-headed Medusa with her unruly serpentine locks, the city’s marginalised communities must be erased from the mainstream narrative of development. Roy writes, “Skyscrapers and steel factories sprang up where forests used to be, rivers were bottled and sold in supermarkets, fish were tinned, mountains mined and turned into shining missiles.”

Thus, in the scheme of neoliberalism, “Delhi cannot afford to look like Medusa. Medusa’s unobliging and troublesome serpents cannot be defanged or severed so she needs to be walled out and kept out of bounds. Delhi needs to be propped up like a glam doll to attract dollar billionaires and foreign investors and paraded in borrowed clothes”. This is why, as echoed by Walby, “Within the neoliberal project, equality is most often treated as either irrelevant or as a limit on the project of economic growth.”

Arundhati Roy’s The Ministry of Utmost Happiness is therefore, more than being a work of fiction, a social commentary on the existing realities of gender, class, caste, sexuality which are often brushed under the carpet for fear of revealing the lacunae and loopholes of a democratic society. But without addressing these loopholes and finding solutions to bridge the gaps, it is impossible to envision an equal society where multiple lives can coexist without the threat of coercion, castigation, violence, and censure. Roy’s novel provokes us to think, rethink, imagine, and reimagine our own position, whether privileged or oppressed in society, and eventually work toward an egalitarian and empowered world.

References

Butler, Judith. 2006. Gender Trouble. Routledge Classics. London: Routledge

Foucault, Michel. 1980. Power/Knowledge (ed. C. Gordon). New York: Pantheon Books

Marvasti, Amir. 2004. Qualitative Research in Sociology: An Introduction. London: SAGE Publications

Roy, Arundhati. 2017. The Ministry of Utmost Happiness. New Delhi: Penguin Random House India

Talwar, Shyaonti. 2020. “The City as Medusa, Grandma and Whore in Arundhati Roy’s The Ministry of Utmost Happiness.” postScriptum: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Literary Studies 5(2):259–267

Walby, Sylvia. 2009. Globalization and Inequalities: Complexity and Contested Modernities. London: SAGE Publications Ltd

Featured image source: Chicago Tribune

About the author(s)

With over 10 years’ experience in publishing and journalism, Ipshita Mitra has a Bachelor’s degree in English Literature from Miranda House, DU and holds a PG Diploma in English Journalism from IIMC. She did her MA in Gender and Development Studies and is currently pursuing her PhD in Gender Studies from IGNOU.

She has worked with The Times of India, The Asian Age, The Quint, Om Books International, World Monuments Fund India Association, and The Energy and Resources Institute (TERI). In 2016, her short story ‘Cacophony of Silence’ was published by Nikkei Voice, a Canadian-Japanese newspaper. In 2020, her short story ‘Bohemian Sailor of the Gulf’ was published by Sublunary Editions, a Seattle-based independent publisher. The Indian Quarterly (April–June 2021) published her short fiction, ‘Kabuliwala Returns’. She writes on books, culture, environment, and gender for TerraGreen, The Hindu, Scroll.in, The Wire, Wasafiri, Firstpost, Huffington Post, India Currents, and others. She tweets @ipshita77.