Harnaaz Kaur Sandhu, was recently crowned Miss Universe 2021 in a historical feat, where she brought the title home to India after twenty-one years, the last being by Lara Dutta in 2000. While this is indeed a celebratory occasion for the recipient, and a proud and nostalgic moment for the country, it is also perhaps a moment for introspection on what these titles mean and what the implications of having such pageants are in the first place.

While the world is run amok by uncountable beauty pageants, it is the Big Four that still commands media attention and glamour. They include, the Miss World, Miss Universe, Miss Earth and Miss International with Miss World being the oldest and the Miss Universe being a close second. While beauty pageants originally started by judging and ranking participants on the basis of their physical attributes, today they aim at painting a more holistic picture by focusing on the contestants’ personality, intelligence, talent, character and involvement in social welfare activities, besides their physical attributes. Nonetheless, we must scrutinise whether this shift has really changed the homogenisation of beauty or addressed the problematic politics of such events at all.

The idea of beauty and its problematic homogenisation

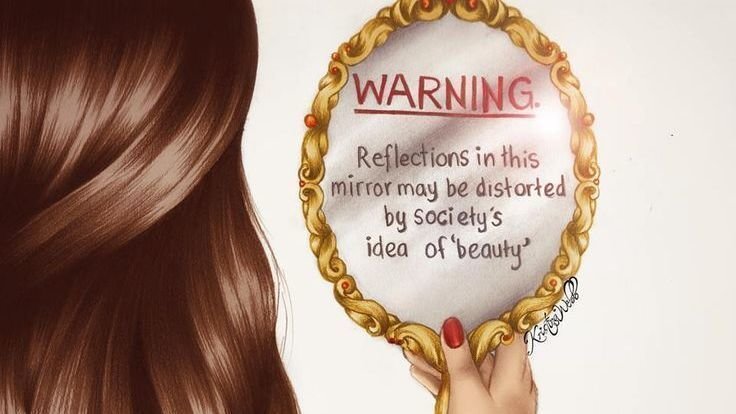

To adhere to the standards of beauty, which are homogenised and standardised across cultures or to not adhere to them – that is perhaps the most relevant question that comes to mind when one thinks of the idea of beauty itself. Beauty, especially that of women, is often deemed as the singularity of their existence where they are stripped off all other traits and characters. They lose all essences that define them to be represented just by their beauty. Thus, a beautiful woman in our collective psyche cannot be athletic, muscular, artistic and heavens forbid, politically opinionated. One only has to glance at the sea of jokes surrounding the beautiful blonde woman to understand the idea.

On the other end of the spectrum are women who aren’t “beautiful”, yet these women too spend financial, emotional, physical and cognitive labor into the act of becoming beautiful. American feminist author and journalist Naomi Wolf, in her critically acclaimed book, The Beauty Myth, succinctly puts it, “The more legal and material hindrances women have broken through, the more strictly and heavily and cruelly images of female beauty have come to weigh upon us… cosmetic surgery became the fastest-growing specialty… Pornography became the main media category, ahead of legitimate films and records combined…”

Clearly, either scenario is a lose-lose for women. Particularly if one pictures the fact that the ‘naturally beautiful’ woman is a myth sold to us by the deadly combination of the fashion industry and the voyeuristic world of social media. The commodification of ‘simplicity’ and ‘natural’ is a white lie made to sell umpteen products made of “herbal ingredients” to give you “natural glow.”

But it is not these abstract and sometimes distant data that is worrisome, it is the replication of it at micro level that is concerning. At schools, college fests, family functions and on festive occasions, ramp walks and beauty contests occur very frequently. The normalisation and replication of pageants in such spaces is rooted in the pedestalisation of the beauty and body image standards set by larger pageants that garner such massive public attention and support. It is the embodying and imbibing of such protocols of beauty that make these pageants rather redundant in their pursuit of empowerment

Leo Tolstoy’s character, Dolly in Anna Karenina, well understood the facades of simplicity when she noted, “Anna had changed into a very simple lawn dress. Dolly looked very carefully at this simple dress. She knew what such simplicity meant and cost.” Therefore, when we analyse the relevance of beauty contests, we must first look into how we conceptualise beauty itself – whether it is a set of attributes that can have a common denominator so as to be judged upon among different individuals, and the extent to which this concept is fueled by how an ideal, beautiful woman should look, think, talk and behave.

In that context, it is hard to rationalise the idea behind ‘crowning‘ one woman the most beautiful, only to see them go ahead and pander to the very problematic standards of beauty they seem to critique through modern day pageants that advocate parity, inclusion and social awareness.

Also read: Navigating Infantalisation, Non-Disabled Beauty Standards & The In-Between

Beauty pageants: Empowerment or disempowerment?

A tightrope between exercising one’s choice and taking the moral high ground, the question of participating in a beauty pageant, consuming it or endorsing it is a tricky one. While being beautiful in a socially approved sense is pedestalised in our society, its absence often places women under an overbearing pressure of performance.

One one hand is the idea that like any individual, women too have the right to commodify their bodies and make a career out of their expression through beauty and fashion. In this context, it is a matter of right for women to monetise their beauty, explore their creative possibilities using the body as a tool and this must carry no ethical baggage.

However, in a world where women for long have been only valued for their reproductive ability and most women have narrated how being beautiful often served as the yardstick for gaining the respect of the opposite gender, it does become a moral imperative for anyone who consumes beauty pageants to mull over the implications of such consumption.

To believe that beauty pageants are dissociated from the realities of our life would be naive. For one, the “beauty queen” selected each year represents the standardised, homogenised and socially reinforced ideals of beauty that the fashion industry constructs and pushes. For comparison, one only has to look at the ideal body type over the decades viz a viz a chart of body types of the crowned Miss Universes.

But it is not these abstract and sometimes distant data that is worrisome, it is the replication of it at micro level that is concerning. At schools, college fests, family functions and on festive occasions, ramp walks and beauty contests occur very frequently. The normalisation and replication of pageants in such spaces is rooted in the pedestalisation of the beauty and body image standards set by larger pageants that garner such massive public attention and support. It is the embodying and imbibing of such protocols of beauty that make these pageants rather redundant in their pursuit of empowerment.

When on one hand, beauty marketing speaks about beauty as the confidence arising from ‘staying true to oneself‘, it is important to investigate how women of colour, and women with varying physical and other attributes, outside of the set standards of pageants are allowed to stay true to themselves.

Pictures of the contestants dressed in Bedouin outfits went viral on social media, and representatives of international human rights organisations indicated that this is an upsetting continuation of cultural appropriation and the erasure of Palestinian culture which has already been threatened to the verge of elimination. Against this backdrop, hosting the event in Israel calls into question the genuineness of the commitment of the pageant to “celebrate women of all cultures and backgrounds”

Miss Universe 2021 : Ideological incongruence and cultural appropriation

The official website of the Miss Universe pageant describes the event thus – “The Miss Universe Organisation (MUO) is a global, inclusive organisation that celebrates women of all cultures and backgrounds and empowers them to realise their goals through experiences that build self- confidence and create opportunities for success.”

While this is indeed an admirable and inclusive list of goals, particularly for an organisation known to host beauty pageants in a world shaped by the nexus of the fashion and cosmetic industry which leaves little space for heterogenous representation and autonomy, however in practice, these ideals are often diluted. The controversy surrounding the venue of the 70th Miss Universe 2021 event is counterproductive to these ideals and cannot be brushed aside.

The pageant was held in Eliat, Israel amidst much turmoil given the ongoing Palestine-Israel conflict where the former has allegedly experienced ethnic cleansing and reports have surfaced of widespread dislocation of Palestinians from their homes. The crisis has been accentuated by the Covid-19 pandemic that has rendered meager health services even more scarce.

Pictures of the contestants dressed in Bedouin outfits went viral on social media, and representatives of international human rights organisations indicated that this is an upsetting continuation of cultural appropriation and the erasure of Palestinian culture which has already been threatened to the verge of elimination. Against this backdrop, hosting the event in Israel calls into question the genuineness of the commitment of the pageant to “celebrate women of all cultures and backgrounds”.

In fact, the turmoil that unfolded has been quite far-spread and statements and reactions of other participating countries in the pageant are very telling in this regard. Miss Malaysia and Miss Indonesia skipped the competition, and South Africa’s government publicly encouraged Miss South Africa Lelela Mswane to follow suit. Miss Universe, Harnaaz Sandhu said, “We come here to unite and to share cultures, This is not where we should talk about disparities. It’s something which talks about unity and inspiring each other.” Miss Sandhu’s statement ignores the underlying fact that monuments of celebration cannot be built on relics of war.

Also read: Miss Universe 2021 Misogyny Offers Anti-Racist Allyship

The idea of critiquing beauty pageants of the standardisation of beauty into monolithic attributes is to not denunciate celebration of beauty or bodily expression, but to question what the perception of beauty, its celebration and the process of such celebration entails. It is also to understand the political making of the ‘beautiful’ and of the ‘ugly’ and in that context evaluate the legacy of these pageants and their limits in shaping our lives.

While entertainment is often atomised from politics, it is rather inapt, particularly when the world of entertainment is built on bricks of cultural appropriation, as is the case with Miss Universe 2021. Often, grand entertainment programmes escape political scrutiny for they are clubbed under the apolitical genre of entertainment. But is high time to hold these pageants accountable, if not necessarily to all the ideals of feminist emancipation, then at the very least to their own self-declared goals.

Featured Image Source: TV Line

About the author(s)

Harshita is a public policy consultant working at the intersection of gender, climate change, and disability. An alumna of Jesus and Mary College, University of Delhi, and the Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex, her work draws on her training in History and Development Studies to unpack gender as a social and structural construct.

In the last question, she was asked to give advice to women but she replied by addressing the youth, thus addressing both men and women. What a brilliant response.