Judiciary in India, as one of the three (independent) organs of the state, is supposed to uphold the rule of law and the spirit and letter of the Constitution. A simple reading of the role of judiciary, will make one see it merely as an implementer of existing legislation and enactments. However in practice, the judiciary is not merely an implementer but also enabler.

Particularly from the late 1970s and 1980 onwards, introducing the Public Interest Litigation that followed in the wake of relaxed locus standi requirements by Justice V. R. Krishna Iyer and P. N. Bhagwat led to a one hand democratisation of the access to justice for the public and on the other, opened the pathway for the delegation of legislative function to the Judiciary. While this later consequence remains debatable, what is notable is that a phase of judicial activism also followed in the wake of instituting the PIL.

Subsequently, the ability of the High Court (hereafter HC) and the Supreme Court (hereafter SC) to take liberal and expansionary reading of the law has while on one hand been applauded by the public, on the other hand, it has invited criticism for judicial overreach from the state and the academia. But given the high bar and the progressive attitude adopted by these centers of justice in recent years, clearly civic society’s expectations are often not being met.

Also read: 8 Feminist Moments From 2021 That Made Us Proud

Subsequently, the ability of the High Court (hereafter HC) and the Supreme Court (hereafter SC) to take liberal and expansionary reading of the law has while on one hand been applauded by the public, on the other hand, it has invited criticism for judicial overreach from the state and the academia. But given the high bar and the progressive attitude adopted by these centers of justice in recent years, clearly civic society’s expectations are often not being met.

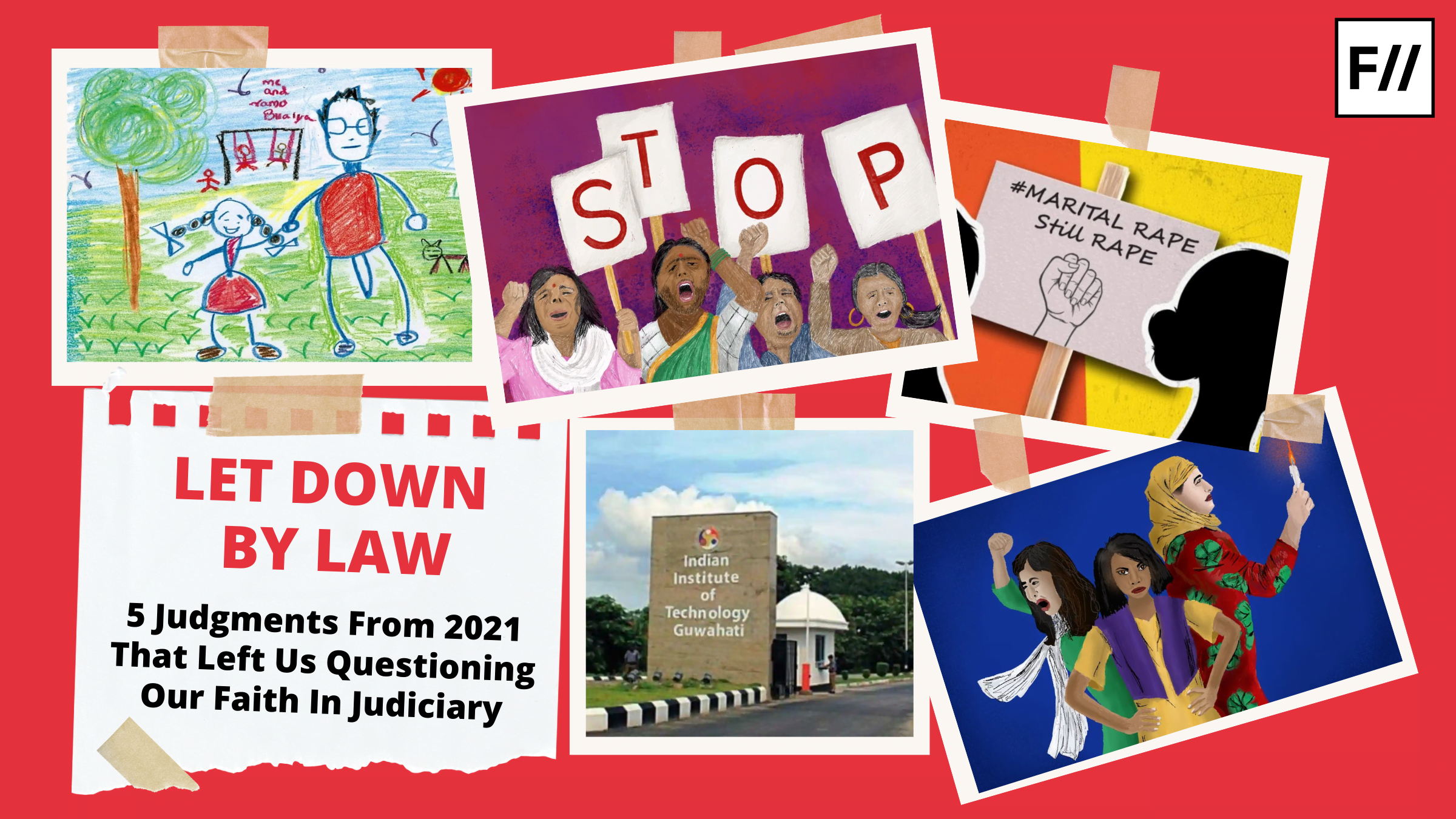

Here are five cases in 2021, when the court not only failed to match the bar set by its predecessors of taking the high and liberal roadway to justice, but also fell short of social morals that it seeks to uphold by creating a just society.

Also read: 6 Women Journalists Who Spoke Truth To Power In 2021

1. Bombay HC : Sexual assault under POCSO needs skin to skin contact

On 19 January 2021, the Nagpur Bench of the Bombay HC acquitted a man of sexual assault on the grounds that pressing the breasts of a child over her clothes without direct skin to skin physical contact does not constitute “sexual assault” under the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act (POCSO). The verdict was delivered by Justice Pushpa V Ganediwala, who observed that “As such, there is no direct physical contact i.e. skin to skin with sexual intent without penetration”. The judgment in its wake bought much uproar and civil protest.

The case in question concerned the accused taking the 12 year old survivor to his home on the pretext of giving her food. Once there, he locked her in the room, attempted to remove her clothes and groped her breasts. The POCSO Act defines sexual assault as when someone “with sexual intent touches the vagina, penis, anus or breast of the child or makes the child touch the vagina, penis, anus or breast of such person or any other person, or does any other act with sexual intent which involves physical contact without penetration is said to commit sexual assault”.

The HC engaged in a reductive reading of the law, allowing the accused to walk free by upholding the letter of the law and not its spirit. The stay on the verdict by the SC in January 2021 and the order by Justice UU Lalit in November 2021 that noted that the act of touching the sexual part of the body or any act involving physical contact if done with sexual intent would amount to sexual assault within POCSO, gave not only the survivor some breathing space but also eased the passage of conviction for future convicts.

2. Allahabad HC : Forced oral sex does not qualify as “aggravated sexual assault”

Justice Anil Kumar Ojha of the Allahabad HC in November 2021, reduced the 10 year jail-sentence given to the convict by the trial court, on the grounds that the act was not aggravated. Ironically, the order preceded the SC’s judgment on the reading and implementation of POCSO by a day.

The case dates back to 2016 and involved the accused taking a 10 year old boy to the temple backyard, where he forced the child to perform oral sex on him. To maintain secrecy, the accused gave the boy twenty rupees and threatened him with dire consequences if he reported the incident. The trial court convicted the accused of “aggravated penetrative sexual assault” and sentenced him as per POCSO to ten years of Jail. While Justice Ojha upheld the conviction of the trial court, he reduced the sentence for he observed that the act in question did not amount to “Aggravated Penetrative Sexual Assault” but only to “Penetrative Sexual Assault”, which carries a lesser sentence in POCSO.

The civic uproar that followed in the wake of judgment was two-fold : one, that the SC had only recently underlined the need to emphasise on the intent rather than just the content of the Act, while making conviction. Secondly, many felt the judgment was a misreading of section 5 of the Act that defines aggravated penetrative sexual assault as any penetrative sexual assault upon a child below the age of twelve years.

That both the Bombay HC and the Allahabad HC judgment are disappointing and regressive is evident from a literal reading of it. But what also makes them perilous is the fact that India is witnessing a silent child sexual assault epidemic. According to the 2007 Ministry of Women and Child Development study, 53% of the surveyed children reported one or more forms of sexual abuse. But the data is only part of the picture. Anuja Gupta, who has been working on the issue of child sexual abuse, especially incestuous abuse, for a quarter of a century, says the official numbers do not tell the full story as a majority of the cases don’t even get reported.

3. Guwahati HC : “Accused is a state asset, is talented.”

On 28 March 2021, a senior male student at IIT-Guwahati lured the survivor to Akshara premises on account of discussing her responsibility as the Joint Secretary of the Finance and Economic Club of the students of the IIT-Guwahati; following it he forcibly administered her alcohol and then allegedly raped her, as per the April 7, FIR. Besides the main accused, there were other accomplices to the crime. The Guwahati HC noted that based on the evidence while a prima facie case exists against the accused, but given that the investigation is complete and the accused will not tamper with evidence so as to jeopardize the investigation and that he is a talented student, bail may be allowed.

The survivor for whom the whole event has been socially, physically and psychologically traumatising and academically dislocating, in an exclusive interview to East Mojo, said, “The High Court has released him on bail saying he is a future asset. If the court is deciding on the fact that he is an IITian, then I am also an IITian.” Contrary to the court’s belief that a bail would not jeopardise the investigation, the survivor told East Mojo that the accused person’s friends have reached out to her friends and other students, with threats of sabotaging their positions in clubs and internships if they spoke to authorities about anything they saw that night.

It is not the act of granting bail that is horrifying, it is the logic that preceded the act: The idea that a male accused’s “youth”, “talent” and “potential” to do well far outweighs the trauma inflicted on the survivor. And consequently, that the need to secure the space taken up by the survivor became less significant and hence could be done away with, for the comfort and caliber of her male violator.

4. Madhya Pradesh HC: ‘Chance for course correction’ by granting bail to 18 year old rape accused.

On 8th November, 2021, the Gwalior Bench, presided by Justice Anand Pathak, granted bail to an 18 year old rape accused. The order stated that the bail was granted because the accused was a young boy without any criminal record and a chance was to be given to him for course correction. The bail bond was of INR 50,000 and requires the accused to plant fruit bearing trees and to fence trees and care for them in his locality as part of his community service.

To be noted in the Madhya Pradesh HC and Guwahati HC judgment is not the act of bailing an accused. It is the rationale on which the bail follows: a young boy, talented perhaps and whose transgressions against another while maybe true, can be sidelined for the idea of his redemptive and reformative potential. In the accused’s ability for reform and redemption, the survivor’s narrative does not exist. The survivor’s trauma is invisibilised for the greater good, the greater good amounting to the abuser’s redemption. That in 2021, this century-long trope still holds, that the survivor’s experiences can always be benched, without any accountability and rehabilitation offered towards the survivor, is shameful to say the least. The court by articulating such rationale, not only tells the survivor that her trauma is significantly smaller in relevance but also tells the accused and by extension the society that “Boys will be Boys.”

5. Chhattisgarh HC: Acquits man of marital rape

The Chhattisgarh High Court on August 25, discharged a man from facing trial for “allegedly” raping his wife. Justice N K Chandravanshi, who presided over the case, noted, “in this case, complainant is legally wedded wife of applicant No. 1, therefore, sexual intercourse or any sexual act with her by the applicant No. 1/husband would not constitute an offence of rape, even if it was by force or against her wish.” His observation was based on an exception to Section 375 of IPC which states that “sexual intercourse or sexual act by a man with his own wife, the wife not being under fifteen years of age, is not rape.”

The judgment was regressive not only by professed social standards of morality and debates of consent, but also by judiciary’s own standards, particularly when a few days preceding this judgment was Kerala HC’s laudatory judgement on marital rape. The court essentially reinstated that a married woman is the husband’s property — her body has no sanctity and is trangressable by her husband. She is all, but a slave.

About the author(s)

Harshita is a public policy consultant working at the intersection of gender, climate change, and disability. An alumna of Jesus and Mary College, University of Delhi, and the Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex, her work draws on her training in History and Development Studies to unpack gender as a social and structural construct.