Can we separate the life of any author from the works they produce? How achievable is this vision and why should we consider doing this? These are the kinds of questions that have stayed with biographers and readers for ages. Great literary theorists like Roland Barthes, delving on related issues, declared in his essay The Death of the Author (1967) that the writer’s biographical details were irrelevant when reading a text, that the author and their creation are not related. While that is one view, on the other hand, novelist and literary critic Zadie Smith argues, in her essay Fail Better (2007), that an artwork cannot escape the personality of its creator.

This subject thus becomes all the more urgent when, for instance, the author or artist in question is someone who had a proven record of predatory behavior or was involved in cases of domestic violence, sexual harassment or emotional abuse. In such a case, what responsibilities does a reader incur, on account of engaging with the author through their works, texts and ideas? What potential harm would it imply for the survivor, for the society and for the notion of justice, as well as ethics towards any discipline to which the author supposedly was affiliated with?

What if, I tell you next, that the list of such authors is very long, and many of us have not only engaged intellectually but also worshiped some of them on our ideational journeys? Many of these names today would potentially feature in the #MeToo list, had they been alive today, and many continue to be celebrated and legitimised through the medium of intellectual engagements.

Also read: Rereading Virginia Woolf’s Ableist And Homophobic Rhetoric

Texts, Authors and Ideas

Should we cite the works of the scholars who were charged under sexual harassment? Should we offer academic legitimacy to such people given that their ideas are indispensable to the discipline? However, this is a question for another day, because the primary issue really is not about legitimizing these figures through intellectual engagements and citations. Rather, it is more about evaluating the kind of treatment these people received from the intellectual elites, seated comfortably in the power hierarchy. This implies that harassers do not just have power over women but they also have the social power to get away with it, while they continue to lead “double-lives” of respectability.

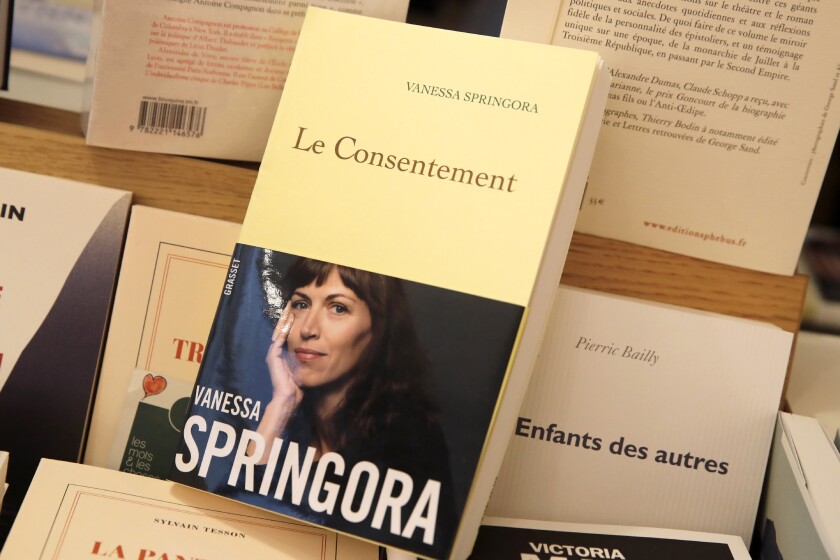

Consider the book Le Consentement (Consent) by Vanessa Springora, a memoir exposé of Gabriel Matzneff, a well-known and much-respected French writer, and also a predator towards teenage girls and pre-teen boys. Despite this, Matzneff was given safe refuge in his own country and was a recipient of a writer’s allowance by the National Centre of the Book. He was awarded the Renaudot, one of France’s most prestigious literary awards.

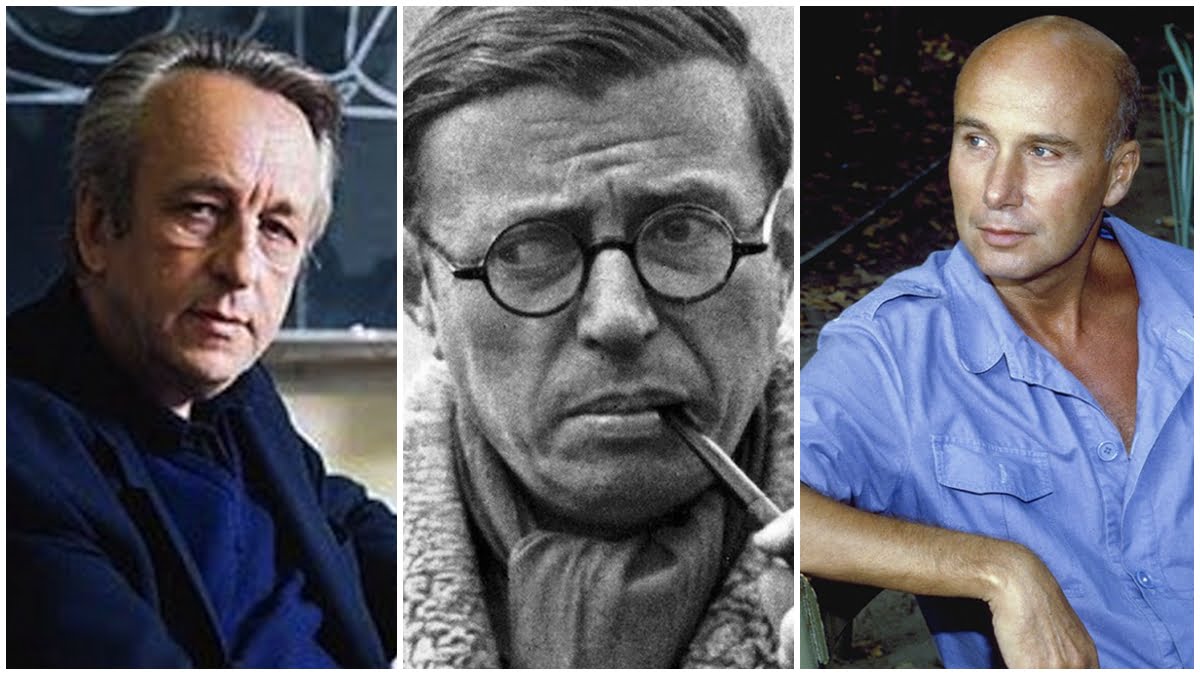

Notably, in the late 1970s, a wave of opinion pieces in French Left-wing newspapers defended adults accused of having relationships with adolescents. Among them were eminent intellectuals, philosophers and psychoanalysts such as Roland Barthes, Gilles Deleuze, Simone de Beauvoir, Jean-Paul Sartre, André Glucksmann and Louis Aragon.

This brings another name to the forefront, which is Jean-Paul Sartre, the flag-bearer of the existentialist philosophy, whose association with Simone de Beauvoir is often invoked as one of the greatest love-stories on the face of the planet. In fact, alluding to this love story, in an interview to Hindi magazine Kadambini, the famous author Amrita Pritam while describing the nature of her bond with the famous lyricist Sahir Ludhianvi, told the interviewer that “Sahir was my Sartre and I was his Simone”.

Little light is shed on the way Sartre constantly lied to the women he was involved with (Sartre called them “little fibs,” “half-truths,” and “total lies”), including Beauvoir. Sartre took the view that there were some people one simply had to lie to. There exists accounts that discuss how the duo worked as serial seducers who used their apparently lofty philosophy as a springboard to excuse their multiple liaisons, often with under-age teenagers who were broken by the experience, and among these while one took to self-harming, another died by suicide, not to talk about Simone’s own reaction to Sartre’s faithlessness.

However, little light is shed on the way Sartre, otherwise the advocate of truth-telling, constantly lied to the women he was involved with (Sartre called them “little fibs,” “half-truths,” and “total lies”), including Beauvoir. Sartre took the view that there were some people one simply had to lie to. There exists accounts that discuss how the duo worked as serial seducers who used their apparently lofty philosophy as a springboard to excuse their multiple liaisons, often with under-age teenagers who were broken by the experience, and among these while one took to self-harming, another died by suicide, not to talk about Simone’s own reaction to Sartre’s faithlessness.

Another great Marxist scholar of twentieth century, Louis Althusser, murdered his wife, Hélène Rytmann, a sociologist, and famously got away with it on the pretext of a medical condition. Geraldine Finn in Why Althusser Killed His Wife writes that they have always killed their wives, either literally or figuratively, by reproducing the violent patriarchal structure. Michel Foucault’s literary credentials are endless from theorising power and knowledge to writing the History of Sexuality. He was a radical scholar who was accused of molesting underage boys in Tunisia.

Thus, these names are not just names, they have a community of intellectuals, a network of ideas, theories and philosophies invested in and through them. Not just ideas, but their actions have also altered the lives of people and the harm inflicted cannot go unaccounted for: this is a point we as readers will have to reckon with as we engage with their works. The stakes, therefore, multiply by manifold and the question of ethics as well as responsibility of engaging with the authors through their texts becomes pertinent.

Can ideas absolve iconic authors of their abuse

Does practical relevance of the works and ideas of such authors and scholars absolve them of their abuse and the responsibility towards ethics of intellectual engagements? Clearly, it cannot be the ethics of the subject. Then how do we continue to engage with their ideas?

The contentious question here is why we continue with the scholarship in the first place. The scholarship of such kind which seemingly appears indispensable to a subject, is often referred as the epistemic authority on the scholarship. Their ideas act as the cornerstone to build on the new concepts and to theorise contemporary issues. Political philosophers take the ideas and existing theories in order to debate, criticise and reconstruct the web of concepts to solve the socio-political problems. Brian Leiter in Academic Ethics: Should Scholars Avoid Citing the Work of Awful People? argues that scholarship is about advancing knowledge within a discipline and failure to citation is harmful as it would hinder the advancement of scholarship, leading to distortion of ideas.

William Lewis discusses a distinction of externalist and internalist approach to reading, where the internalist approach only focuses on the philosophical exercise of the author rather than their biographical sketch. To Lewis, dismissing ideas of scholars like Althusser amounts to an injury to philosophy, as arguably no other scholar has contributed to Marxist scholarship in a way that ignited a curious chain of the production of numerous works building further from his ideas.

Also read: Carnatic Music’s #MeToo: How Media Defeated The Cause By Enabling The Artistes

The externalist approach or the biographical approach for Lewis is reductionist and reduces the ideas to particular events in the life of the author. However, that does not answer the question that what does this continued involvement with their ideas imply for ethics of intellectual engagement as well as the moral harm that comes off from similar structures of power within which volunteers in knowledge operate.

Projecting any author as the flag-bearer of any particular knowledge tradition, should only come with caution, unless one is employing this to highlight the errors in certain lines of thought. Hero-worship in philosophy is as much a misplaced act as it is in politics. Irrespective of how appealing a body of knowledge is to us, it is our added responsibility, as teachers, students, intellectuals, and readers to carry forward the ethics of engagement with ideas in such a way that the point of inquiry should not come from an oblivious ignorance to acts of the authors in question.

The dilemmas that remain

Can we disqualify people from philosophy for their misdeeds and misconduct and if that is to happen, then what does one expect of the philosophical enterprise to retain? There have been authors who have supported slavery while some were actual Nazis and many, unabashedly sexual predators. Engaging with their ideas only from a perspective of hyper-enlightenment, could lead to these authors’ entire disassociation from their political and social surroundings and thus, their acts.

However, ideas cannot and should not be the means to bestow legitimacy upon predators. Therefore, projecting any author as the flag-bearer of any particular knowledge tradition, should only come with caution, unless one is employing this to highlight the errors in certain lines of thought. Hero-worship in philosophy is as much a misplaced act as it is in politics. Irrespective of how appealing a body of knowledge is to us, it is our added responsibility, as teachers, students, intellectuals, and readers to carry forward the ethics of engagement with ideas in such a way that the point of inquiry should not come from an oblivious ignorance to acts of the authors in question.

Kanchan is currently pursuing research at JNU, New Delhi.

About the author(s)

Sana is a research scholar in Political theory, which also happens to be her love of the life. An avid reader, she aspires for a career where she would be paid for reading and reading. With a passion for reading "acknowledgement pages and dedications" by the authors in their books, She hopes to establish an archive of acknowledgement pages one day.