The role that the South Asian culture plays in the accounts that needed #MeToo to be able to come to the forefront, and the reactions and consequences that the victims received is obvious. Denying female sexual agency unless there is an opportunity to fetishise it and seeing sex as something which the woman ‘gives’ and the man ‘takes’, the equivalence of not engaging in sexual activities as a form of ‘purity’ for women, and seeing someone who has been assaulted or raped as someone whose ‘izzat’ has been lost, is just the tip of the iceberg.

It is also important to note that this patriarchal denial of female sexual agency also leads to problems for male and female victims of sexual harassment and assault whose perpetrators are women. The subtle and obvious conditioning that takes place in the context of sex in South Asian patriarchal culture makes any attempt at seeking justice, or even speaking up about being a survivor, an absolute uphill battle.

However, the assumption that in European cultures, where sex and sexuality are more openly talked about, women are ‘safer’ or ‘more protected’ would be based on a misunderstanding of the central problem. The presence of sexual liberty in a nation’s culture does not guarantee equality if that liberty is still exercised within the boundaries of the patriarchy and is still defined through the male gaze and used to cater to it. Sandra Muller’s #MeToo fight since she started the #ExposeYourPig social media campaign in 2017 in France is representative of just that.

Also read: How Does One Ethically Engage With Texts By Problematic Authors?

The assumption that in European cultures, where sex and sexuality are more openly talked about, women are ‘safer’ or ‘more protected’ would be based on a misunderstanding of the central problem. The presence of sexual liberty in a nation’s culture does not guarantee equality if that liberty is still exercised within the boundaries of the patriarchy and is still defined through the male gaze and used to cater to it. Sandra Muller’s #MeToo fight since she started the #ExposeYourPig social media campaign in 2017 in France is representative of just that.

Reception and Responses

Amongst other backlash, the movement was publicly criticized by a collective of 100 women in a piece published in ‘Le Monde’. Titled ‘Nous défendons une liberté d’importuner, indispensable à la liberté sexuelle’ (“We defend a freedom to annoy, essential to sexual freedom”), the co-signees of the piece included French personalities like Ingrid Caven and Catherine Millet. While the piece acknowledged the importance of protection against harassment and abuse, especially in the workplace, it saw the #MeToo movement as something that could potentially curtail the sexual freedom that French society embraces. It reads, ‘This fever of sending “pigs” to the slaughterhouse, far from helping women to empower themselves, actually serves the interests of the enemies of sexual freedom, religious extremists, the worst reactionaries and those who believe, in reality, name of a substantial conception of good and the Victorian morality that goes with it, that women are beings “apart”, children with adult faces, claiming to be protected.’

The assumption that this paragraph bases its argument on is that the presence of an acknowledgement of the sexual agency of women in a culture guarantees the presence of informed and free consent within it. However, if the sexual agency of women is perceived to be threatened by a movement focused on consent, then one needs to ask the question of who this particular understanding of agency is ‘serving’.

The Case of Matzneff

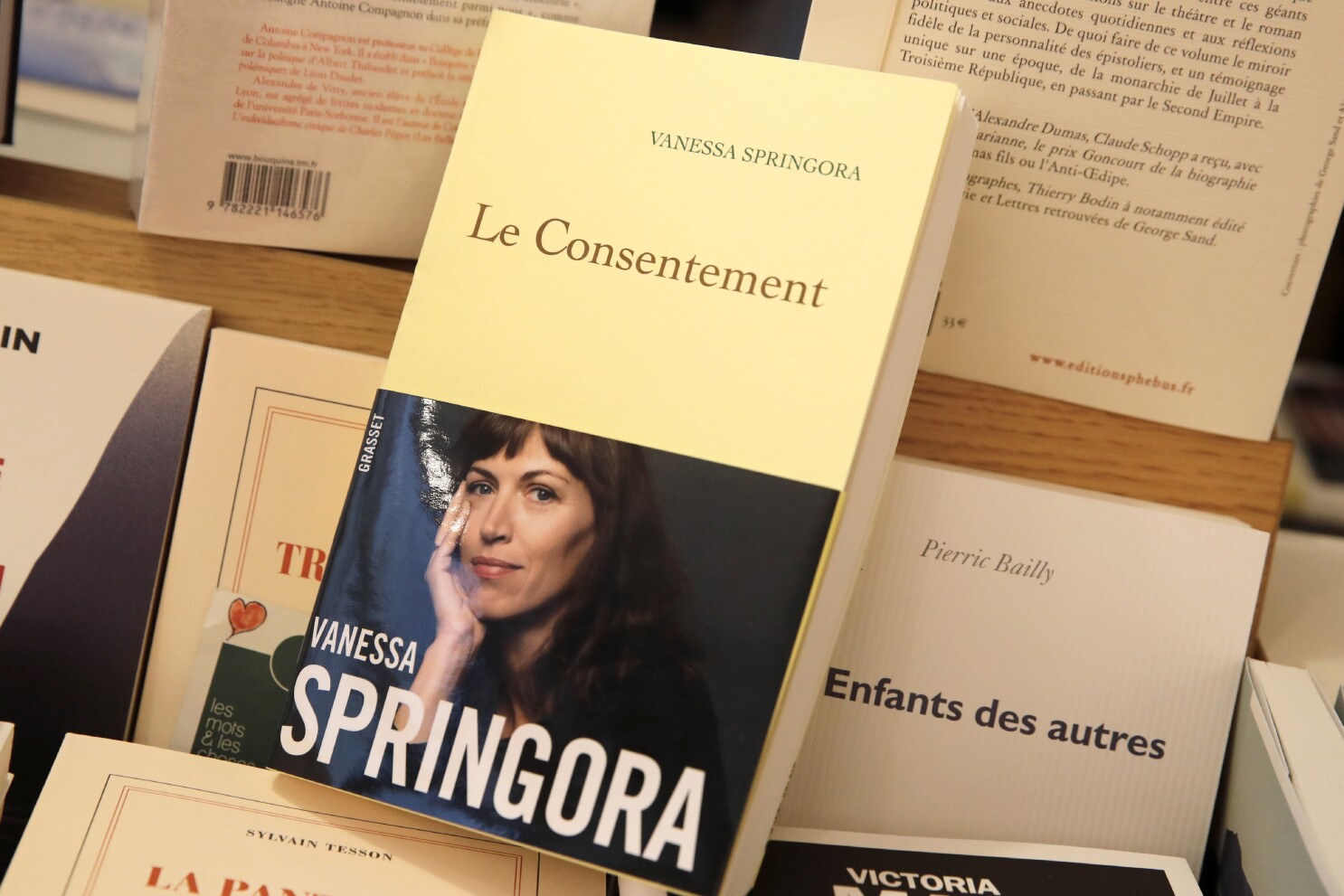

This is exactly what is explored by Vanessa Springora’s book on the trauma of having been in a ‘relationship’ with the French literary personality Gabriel Matzneff when she was fourteen years old. Titled ‘Le Consentement’, it traces her life to ask fundamental questions about power imbalances and cultural understandings of consent. Springora talks not only about people not raising red flags over this arrangement that she had with the then fifty-year-old Matzneff, but actually encouraging it and seeing it as something that she should feel ‘chosen’ for.

The incidences that she talked about in her memoir include the abuser visiting her while she was hospitalized to no one’s objection, and her confession to the paediatrician that she experiences pain when he has ‘sex’ with her leading to the doctor offering to operate on her hymen. He would also regularly come to pick her up from school, and instead of the teachers seeing that as a red flag, one actually talked to Springora about their literary admiration for Matzneff.

When the police had received anonymous letters about the ‘relationship, he moved into a hotel with her so that he could not be traced at his residence. She told the New Yorker, “Sexual abuse, and especially that of minors, is sadly universal, but what’s particular to France in this story is the impunity, the silence that was imposed, not to protect a family or an institution but, rather, a literary figure who was placed at the top of the cultural pyramid.”

Consequences And Consent

It is also noteworthy that she was not a one-off case for Matzneff: he was rather publicly and adoringly known in France for his perverse attraction towards children. In fact, his published diaries actually include accounts of having multiple children- some as young as eight years old- in bed with him at once. Following the publication of the book, a case has been filed by the organisation l’Ange Bleu and the now eighty-three-year old Matzneff has been charged for promoting paedophilia through his books and public appearances.

The understanding of the conversation around the concept of consent has evolved in France, prompted in part by Springora’s memoir and in part by the global feminist discourse. Just like the shaming and denial of female sexual agency in Eastern cultures creates space for exploitation, the presence of an understanding of ‘sexual freedom’ through the patriarchal and powerful male gaze in Western cultures does the same thing.

At the same time, the understanding of the conversation around the concept of consent has evolved in France, prompted in part by Springora’s memoir and in part by the global feminist discourse. Just like the shaming and denial of female sexual agency in Eastern cultures creates space for exploitation, the presence of an understanding of ‘sexual freedom’ through the patriarchal and powerful male gaze in Western cultures does the same thing.

This is why in 2019, Sandra Muller lost a defamation case in France against the ‘pig’ that she had named on Twitter. It is in 2021, without any significant change in facts or evidence, she finally won her appeal against that judgement because the French court and public seem to have taken note of the nuanced conversation around consent which is a huge global consequence of the #MeToo movement. Our global cultural understanding of consent has been in need of a reform for a long time, and #MeToo has finally given space for the world to take the first step towards that direction.

About the author(s)

Khushi Bajaj (she/her) is an intersectional feminist and writer who holds an MSc in Media and Communications from the London School of Economics. Her work has previously been published by Penguin Random House, erbacce-press, Metro UK, Diva, Hindustan Times, and more. She is passionate about advocating for social justice and believing in the revolutionary capacity of kindness. She can be reached through email (khushi.bajaj1234@gmail.com).