Trigger warning: Mention of torture, rape

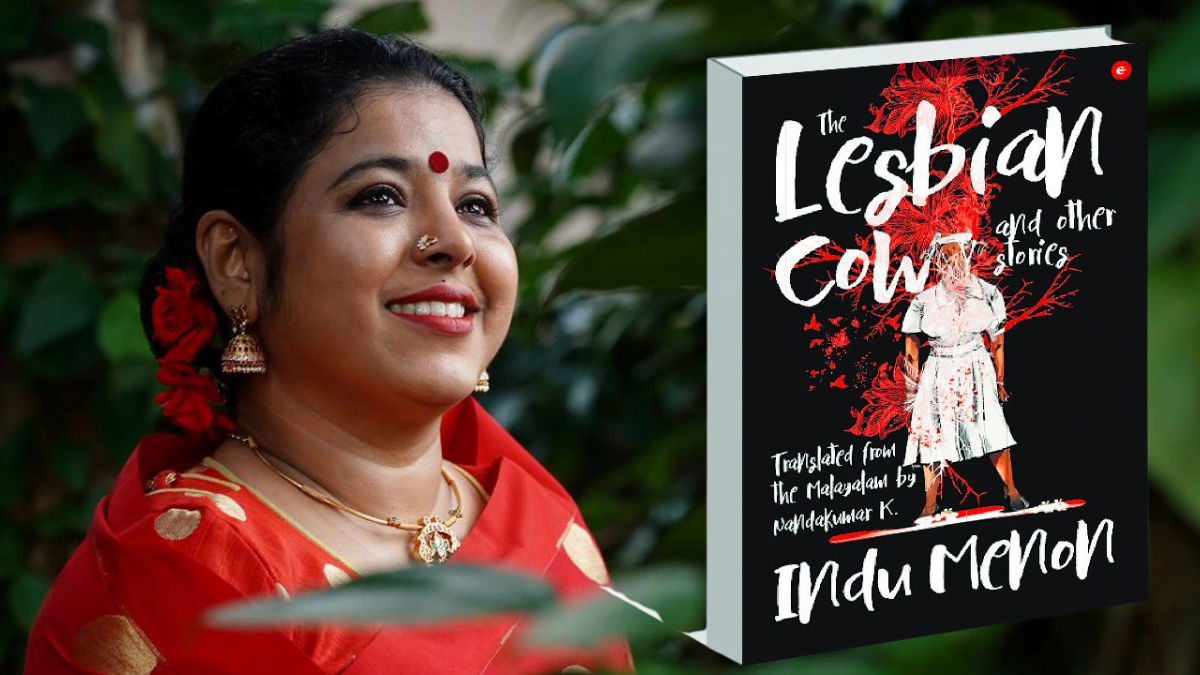

It is a matter of unfortunate literary consequence that the new volume of short stories by the Malayalam writer Smt. Indu Menon translated into English by Nandakumar K for Eka Publications, 2021 is entitled The Lesbian Cow and Other Stories. In the English-speaking world, the word “cow” when used with reference to women is a sexist slur.

A “cow” is what a sexist man (or woman) would call a woman who is perceived to be sexually unattractive, lazy, useless, dense, stupid etc. Adding the nominal descriptor “lesbian” to this slur – “lesbian cow” – makes the title of this new collection a sexist and a homophobic slur. Calling any woman a “lesbian cow” in the English-speaking world would most definitely be answered with a sock to the jaw or obscenities that would turn your face red.

With perhaps two notable exceptions, the sixteen stories in this new collection evidence what we may call the international marketing of trauma porn as eminent literature in the context of the contemporary Malayalam literary scene, particularly, the growing corpus of feminist and intersectional representations from the state. Trauma porn is the intentional representation and marketing of marginalised people’s pain and suffering from the outside as entertainment in a manner that is comfortable to you, the author, the reader, and the audience, and asks nothing of you other than a few minutes of your time.

Moreover, trauma porn leaves you with a satisfied feeling, sometimes accompanied with a visceral thrill of having been part of someone else’s suffering for a little bit before you move on with your life. There is no call to action, no call to change, no call to a better life. There are aesthetic effects that, if you are not alert and careful, make you turn your gaze away from the frame of trauma to comment on the beauty of the representation of someone else’s pain and suffering.

Though The Lesbian Cow and Other Stories has been labeled intersectional feminist literature, most of the stories in this collection exemplify the fundamental characteristics of trauma porn. The story that opens the collection, “The Creature” embodies most, if not all, of Menon’s favorite tropes: the abject “victim,” often a woman or an Adivasi, the debauched attackers, often men of relative class, caste and official superiority, long, long, descriptive passages of physical torture intermingled with mystified depictions of nature, then the traumatic violence at the center of the story foreclosed and imploded by a reverting back to a religious reference, a goddess, a festival, a ritual or a rite

As a genre, trauma porn is nothing new in Kerala. Malayalam films in the late 70s and the 80s extensively marketed trauma porn in the form of violent rape scenes and scenes of extreme humiliation and dehumanisation of Adivasis, Dalits and women, though such representations would not be possible in a mainstream film made in 2021.

For instance, we are a society that produced one of the most beautiful films about the Adivasi ethos, director Shareef Easa’s brilliant Kanthan: The Lover of Colour (2018). So, the old formula of fifteen minutes of an extended rape scene, shown with the woman crying and pleading with her attacker, followed by two minutes of moral discussion about why rape is immoral is not possible anymore in Malayalam cinema. But literature appears to have lower standards.

The usual response by creators of trauma porn is that they are doing this to draw attention to the issues. However, showing a woman getting raped, and the woman killing her attacker in self-defense do not condemn rape. It is just a story to make the reader feel comfortable for the moment; comfortable that they are engaged with social issues, that they are empathic creatures. The world that we see in such stories is inert, static, almost like the past with no traction to the present or plans for the future.

The documentation of “reality,” upon which such stories sell, appears to be a voyeuristic activity. It is in the absence of taking positive action to change the structures of oppression through your imagination, that trauma porn becomes merely performative.

This is not to say that trauma porn does not have a place in the world of artistic representation. It does. It is simply a matter of deciding where to place trauma porn. Highlighting and uplifting trauma porn as eminent literature reflects poorly on the society that makes such pronouncements.

Though The Lesbian Cow and Other Stories has been labeled intersectional feminist literature, most of the stories in this collection exemplify the fundamental characteristics of trauma porn. The story that opens the collection, “The Creature” embodies most, if not all, of Menon’s favorite tropes: the abject “victim,” often a woman or an Adivasi, the debauched attackers, often men of relative class, caste and official superiority, long, long, descriptive passages of physical torture intermingled with mystified depictions of nature, then the traumatic violence at the center of the story foreclosed and imploded by a reverting back to a religious reference, a goddess, a festival, a ritual or a rite.

For instance, the main Adivasi character in “The Creature” is tortured for bearing witness against a corrupt and powerful mining/government official. This angle of the story is kept in abeyance in preference for mere word painting, description of torture without any purpose, or description whose only purpose is to shock and possibly disgust the reader. Menon’s preferred narrative style follows this formula of description without reflection, without commentary, which aligns it with the genre of torture porn whose goal is to immerse the reader in the world of sensation and not critical thinking.

For instance, here is how Menon describes how Bashundhara, the Adivasi woman, takes revenge on one of her attackers; she hides a razor blade within her vagina which cuts off her attacker’s penis as he rapes her:

“The hacked penis’ blood dripped from the two halves of the blade onto Bashundhara’s fingers, and thence to the floor, like Nagoba’s scarlet vermillion bindi. In the bloodbath, the room appeared to have turned increasingly lurid. The hacked male penis, a propitiatory offering to Nagoba, wiggled for a brief time like a billion-year old primordial snake and sank to the bottom of the water closet.” (“The Creature”)

This mode of mere description without any commentary that leaves the reader learning nothing about how this act of revenge affected either Bashundhara or her attacker is typical of Menon’s narrative style. There is a lot of surface, a lot of foreground, but very little underneath. Menon’s narrator treats the victim and the oppressor(s) with the same descriptive flourish; humiliation, indignity, pain, dismemberment, death, all narrated with a surfeit of details, but mostly without any narrative voice. It renders such scenes into mere spectacle.

The most egregious application of this absent narrative voice is in the story “D” where the narrator draws a parallel between three political murders: Robert-Francois Damiens on 28 March 1757, Chella Durai Dipakaran on 28 March 2010, and Pasu Malai Dipakaran on 28 March 2014. Menon cites the French philosopher Michel Foucault as an influence on this story in her list of acknowledgements.

The collection does not have a foreword or an author’s preface that situates the stories in their contexts, but the translator’s introduction notes that the “brutes and angels of death in her stories” are “taken on by women who trump over them in the end” (“Retribution as Redemption”). Regardless of this assertion, with the exception of two notable stories, “A Story Posted in 1975,” and “Virgins who Walk on Water,” the protagonists of all the other stories in this collection — mostly women, and a handful of Adivasi men –are defeated, mutilated, tortured, raped, or murdered

Foucault begins his monumental Discipline and Punish: The Birth of Prison (1977) with the anecdote of the torture and murder of the semi-mad house servant Robert-Francois Damiens for the attempted regicide of King Louis XV in 1757. Foucault copies verbatim the torture report from the official and historical records of this public execution and includes sources and cites.

Following this, Foucault uses this historical data of punitive public torture to show a theoretical realignment of the position of the human body in crime and punishment as Europe turned away from torture as public spectacle to the invisible and intimate and equally destructive modes of punishment in the modern, carceral nation-state in the form of prisons.

Foucault, later in the book, also characterises public torture as a site of resistance through his analysis of a botched public execution in France at the end of the 17th century which led the outraged public to destroy the gallows and beat up the executioner. So, public torture has some redemptive outcomes at times, though not always. Foucault’s Damiens narrative is thus, part of a larger theoretical discussion.

In Menon’s story “D,” the torture description becomes an end in itself and punitive execution as public spectacle is intentionally rebirthed without any narrative intervention. Menon elaborately describes the rape of a prisoner by a police dog named “100”:

“Go, 100, go”

What followed was a horrendous scene. Tamilchelvi bolted through the door. Showing signs of a dog in heat, the Rottweiler was in hot pursuit. It had been trained specifically to copulate with women. Its organ was exposed and erect, like the raised spectre of authority. The soldiers cheered it on, turned on by the novelty of the perversion. The trainer cracked the whip, which flashed through the air. The dog brought down Chelvi, turned her over, and started attacking her from the back with its beastly agility. (“D”)

In the age of snuff and torture porn films, a multi-billion-dollar industry, it behooves us to understand, as Menon does here, that there are people amongst us who would be “turned on by the novelty of the perversion.” Evidently, Menon appears to be okay with taking this risk of turning on people with her own writing.

The Lesbian Cow and Other Stories is littered with scenes of gratuitous violence like the one above. Indeed, the (ill)famed Casanova who allegedly witnessed the public torture and execution of Damiens noted in his Journals that he sat with two women who did not find Damiens’ torture disturbing because of their loyalty to King Louis XV: “that their horror at the wretch’s wickedness prevented them feeling that compassion which his unheard-of torments should have excited.” You cannot predict or control who is reading torture or why they are reading it.

An overdetermined undercurrent of a father-daughter incest trope runs throughout the stories, which culminates in the made-to-order erotica “Premasutra,” which Menon has “Dedicated to all the women in this world,” (certainly not to survivors of incest, one can only hope!) where the man has sex with both the mother and the daughter. This story really could be the archetype of all of Menon’s men and women. “Ugly” women, such as the “lesbian cow,” are rapists, like men. The relentless duplication of such formulaic characters and plot points eventually renders these stories somewhat ludicrous rather than disturbing

The collection does not have a foreword or an author’s preface that situates the stories in their contexts, but the translator’s introduction notes that the “brutes and angels of death in her stories” are “taken on by women who trump over them in the end” (“Retribution as Redemption”). Regardless of this assertion, with the exception of two notable stories, “A Story Posted in 1975,” and “Virgins who Walk on Water,” the protagonists of all the other stories in this collection — mostly women, and a handful of Adivasi men –are defeated, mutilated, tortured, raped, or murdered.

The high school aged heroine of “Daddy, You Bastard” is brutally raped; the hero and heroine of “The Muslim with Hindu Features,” resemble a 1980s Malayalam movie; the daughter hangs herself in “Chaklian”; one woman is raped and murdered and the other mystified into a proxy goddess in “The Bloodthirsty Kali”; sister turns against sister in “Secret of the Soul”; a widow is thrown from a train and killed in “The Lexicon of Kisses”; brother kills brother in “The Red Seeds of Papaya,” and on and on.

Also read: Bodies Online: Image-Based Sexual Abuse Or ‘Revenge Porn’ In India

Menon’s women are mostly seductively beautiful temptresses – they are always seen through the male gaze — with full, buxom bodies, full lips, long black hair flying loose, big bindis and are completely all body; they don’t seem to have a mind. The men are all potential rapists who don’t seem to have anything other than power, seduction and rape on their minds.

An overdetermined undercurrent of a father-daughter incest trope runs throughout the stories, which culminates in the made-to-order erotica “Premasutra,” which Menon has “Dedicated to all the women in this world,” (certainly not to survivors of incest, one can only hope!) where the man has sex with both the mother and the daughter. This story really could be the archetype of all of Menon’s men and women. “Ugly” women, such as the “lesbian cow,” are rapists, like men. The relentless duplication of such formulaic characters and plot points eventually renders these stories somewhat ludicrous rather than disturbing.

In the two stories that speak to a genuine human spirit that we can understand – “A Story Posted in 1975,” and “Virgins who Walk on Water,” we encounter characters who stand up for their lives, however small and modest these might be. I particularly liked “Virgins Who Walk on Water.” The lesbian lovers, Amuda and Raziya, realise and accept their love and desire for each other like a revelation in the darkness:

“Lightning streaked across the sky like a flashing Urumi. Raziya withdrew. Her eyelashes had shrunk from the moisture. In the next flash of lightning, they saw each other’s nakedness. They were like snakes that had moulted, coiling and uncoiling.” (“Virgins who Walk on Water”)

Likewise, “A Story Posted in 1975,” is a memorable indictment of the inhuman policies of Indira Gandhi’s Emergency period and its nefarious and tragic consequences on the poor and the dispossessed. The Adivasi character who ends up sweeping up used condoms at a brothel recollects his route thence through the violence of Sanjay Gandhi’s mass sterilisation program:

“My life, the red bucket, the squalor, my unborn children. I felt contempt towards myself for the first time.

I got out into the yard and started to walk. I looked at the sky and the earth, at the trees and the soil, at people performing ablutions under the public tap. I saw people who were dancing with happiness and someone kicking away the transistor kept in front of the house. Then I counted the money in hand to check if it was sufficient to bid for the services of the adivasi girl who had been newly brought in, and walked back into the whorehouse.” (“A Story Posted in 1975”)

This voice of quiet introspection is rare in the stories included in The Lesbian Cow and Other Stories. Menon’s works are likely to reach her intended audience if this thoughtful narrative voice is nurtured, rather than the excesses of trauma porn that overwhelmingly mar her literary output.

Wonderfully nuanced review.