Content warning: some excerpts from the book mentioned in this article may be triggering to read.

The #MeToo movement of 2018 took the feminist discourse to institutions above and beyond the internet. The nuances of sexual harassment and violence were now discussed at dinner tables and in TV news debates. Needless to say, it shook the conscience of many men, forcing them to reflect on their actions seriously.

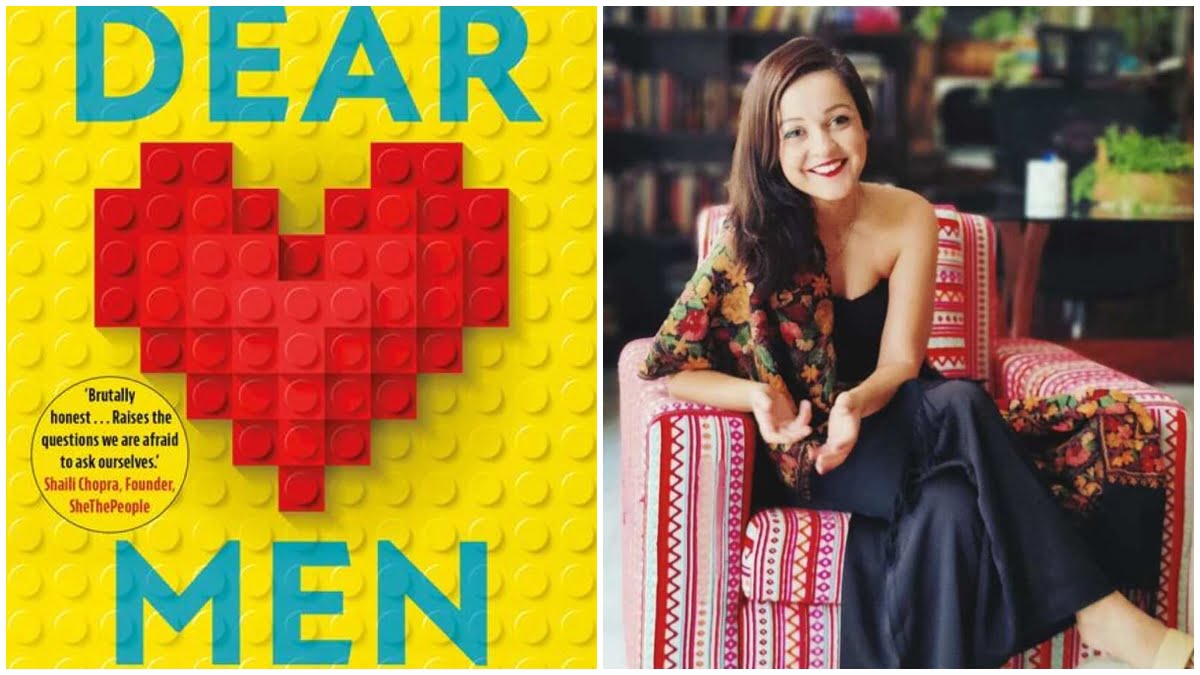

Cases like Aziz Ansari’s warranted a conversation on dating etiquette — or the lack of it — highlighting the need for some vocabulary, a go-to source, that could help put complex situations into words for potential victims of sexual assault in intimate settings. Prachi Gangwani’s book, ‘Dear Men: Masculinity and Modern Love in #MeToo India‘, could have been one such source.

Written by a founder of a women’s online lifestyle magazine and former family and couples counsellor, Dear Men intends to center men in the discourse around sex, dating, and relationships in India, attempting to understand their perspective on the same. Gangwani even states in the introduction of Dear Men that men have “been on the periphery of the gender revolution”, referring to the strides women’s movements have made both in India and the West. And yet, the book opens with the following dedication:

To all the men who broke women’s hearts. Without you, there would be no need for a book like this.

Also read: Sindhu Rajasekaran’s ‘Smashing The Patriarchy’: A Book That Fails To Convince

Considering that this book intends to be a ‘dating guide for men’, inviting them into the discourse they have been left out of, my sensibilities nudge me to ask: Why start a dialogue with an ominous remark such as this?

The reason this line stuck with me is that there is a palpable dissonance in the title of the book and its contents. When I think of a dating guide, I think of a manifesto — a rulebook — that unpacks norms and behaviours and explains why we must follow certain rules. There is much to unearth within the convoluted nature of online dating and the psyche of Indian men, especially in a country that is a melting pot of cultures and experiences. But the book misses the mark by a mile, merely touching upon the surface of the regressive nature of men who have grown up in patriarchal households.

Men are perpetrators, women are victims

In a chapter titled ‘Consent 101’ in Dear Men, Gangwani narrates a particularly disturbing excerpt from her interview with a mother of two young girls. In it, the mother, Akanksha, explains why she chooses to fake orgasms during sex with her husband. “My father was in the ICU with COVID and my husband just wanted to have sex…I told him I can’t and this man takes it personally.” She continues, “Kuch ho jata hai inko. Men can’t take it when we say no. Something — I don’t know what it is…He just does it. So I also just do it. Even when I don’t enjoy it.”

Consent is and has been a highly controversial subject since #MeToo. Some argue that enthusiastic consent is the only acceptable form of consent, while others argue that it is layered and complex. But this excerpt in particular doesn’t explore either thought process — it exists solely to rile the reader up.

Dear Men, over and over, showcases that many urban men are still regressive, as if single women sharing those spaces (and their mothers) weren’t already aware of it. Like the above-mentioned excerpt, almost every chapter begins with a provocative, sometimes triggering statement made by a man Gangwani has interviewed for the book, which forces the reader to read on simply because it incites anger. As a content writer by profession, I believe this is a great hook and strategy to get someone to read your work, but there’s only so much your opening statement can do.

At the end of every chapter, one is left feeling incomplete. For instance, the section containing the above-mentioned excerpt ends with a psychologist stating that communication is the only solution, and for couples who can’t communicate, therapy is the only solution. It’s hard to feel satisfied when a solution to deep-rooted issues is a generalised ‘communication’ and ‘therapy’, with no mention of what either means for people belonging to different socio-economic strata.

A dating guide for men would ideally address men in a manner that doesn’t demonise them, but Gangwani’s book has, unfortunately, done that throughout. Whether it is about men’s perspective on sex, marriage, #MeToo, or consent, it refuses to showcase them also as victims of the patriarchy, and latches on to the provocative statements they have made. It makes them look like linear-thinking, unidimensional, almost broken beings, which one cannot help but feel angry about.

Because so few women have been featured in Dear Men, it has painted them as perpetual victims of the patriarchy who couldn’t possibly go out on a Tinder date without the risk of getting assaulted. That is a dangerous precedent to set, especially because dating is as much a site of pleasure and freedom as it can be a site of violence. The book paints women as people without agency, and that every decision they make — whether it is to sleep with someone or say ‘no’ — they make with absolutely no control over the consequences.

‘Dear Men’ does not speak of dating and sex as something both parties can (and have) enjoyed, but makes every experience sound like a cautionary tale. Where’s the empowerment in that?

Dear Men does not speak of dating and sex as something both parties can (and have) enjoyed, but makes every experience sound like a cautionary tale. Where’s the empowerment in that?

Whom is the book for?

Perhaps it’s important at this point to mention that Dear Men is a product of interviews with over 70 men and over 20 women, all belonging to urban India. The sample size of this research is highly contentious — given that India is one of the few countries in the world with an enormous youth population (and is thus the primary target for dating apps), double digits cannot even begin to cover the multitude of experiences we have with dating and relationships. This begs the question: whom does this book serve?

For those of us who aren’t new to the discourse around dating and men — social media seconds as a masterclass for many of us — the book doesn’t have many groundbreaking discoveries. Gangwani gets a few things right in Dear Men — explaining vaguely familiar concepts such as ‘toxic masculinity’ and ‘the man box’ succinctly, for instance, as they help us ascribe a pattern to men’s behaviour. But it often uses these concepts as a crutch to explain nearly everything that is wrong with men, leaving no room to question the role of rigid structures that men are a part of.

Sure, it’s easy to attribute a man’s need to be the sole earner in the family or not knowing how to cook to toxic masculinity, but this behaviour is also a product of economic policies, social sanctions, and capitalist exploitation that forces men to work long hours, earn more than their peers, and focus less on family and children. Women are, by and large, considered secondary earners due to these unspoken rules, which adds to men’s conditioning and belief that it is their job to earn. Toxic masculinity derived from a patriarchal family structure is merely a part of it.

If this book is for men, it has not achieved its goal of being a dating guide. Trying to start a dialogue with someone by painting them as regressive and inherently misogynistic cannot and will not work. One cannot shame someone into being better.

If this book is for those largely unfamiliar with the dating scene, the book at best offers a cautionary tale, telling women that they will always be potential victims of sexual violence. To make dating a pleasurable experience and help men and women become better at it, it’s important to remember that we cannot speak of violence without speaking of pleasure.

Also read: Book Review: Indu Menon’s ‘The Lesbian Cow And Other Stories’ Is Just An Excess of Trauma Porn

Is therapy the only answer?

A recurring answer to almost every issue raised in the book is therapy. Gangwani has interviewed a practicing therapist (apparently also the only therapist she has spoken to) who talks about the various reasons behind men’s behaviour, with the bottom line being that they must communicate and seek professional help to unlearn toxic masculinity. While that is a straightforward answer, it is also unattainable for many reasons.

Even though the urban population is significantly well-off and largely accepting of psychotherapy, therapy isn’t always a viable solution for all. It requires ample dedication, time, and money, almost making it a practice, which not everyone is cut out to do. Therapy is also a highly individualised practice, which not everyone is comfortable with. Regardless of one’s sex, some people simply do not enjoy talking to a therapist and prefer talking to their close group of friends, which is just as valid an option. Suggesting ‘communication’ and ‘therapy’ as the only solutions is highly myopic.

What Dear Men gets right is this: women in urban India are increasingly gaining financial independence, which is teaching them to take a stand against the patriarchy. Men are only beginning to catch up; the gender gap is so wide that it has caused a dissonance in the expectations they are raised to have by watching the women in their households. There was tremendous potential in exploring this phenomenon, given that women still make up less than 25% of the workforce in India. Unfortunately, the research fell short.

What Dear Men gets right is this: women in urban India are increasingly gaining financial independence, which is teaching them to take a stand against the patriarchy. Men are only beginning to catch up; the gender gap is so wide that it has caused a dissonance in the expectations they are raised to have by watching the women in their households. There was tremendous potential in exploring this phenomenon, given that women still make up less than 25% of the workforce in India. Unfortunately, the research fell short.

Gangwani has successfully brought to the fore important subjects such as the orgasm gap, the masculine manner of dealing with emotions, and the importance of romance and intimacy in casual dating, which are great starting points. She has raised some pertinent questions — such as why men see women as accomplishments and refuse to get in touch with their emotions — but the answers do not move beyond the very obvious: patriarchy. The book could have been so many things, but for now, let’s just call it a 240-page blog post.

About the author(s)

Kanksha Raina is a journalist based in Mumbai, Maharashtra. With a Master's degree in Gender, Culture & Development Studies, Kanksha is passionate about pop culture, cinema, and sexuality, with a particular focus on women's experiences. In her spare time, you can catch her reading, binge-watching her favourite TV show for the 10th time, or spending time with her cat. She is an alumnus of the Asian College of Journalism.