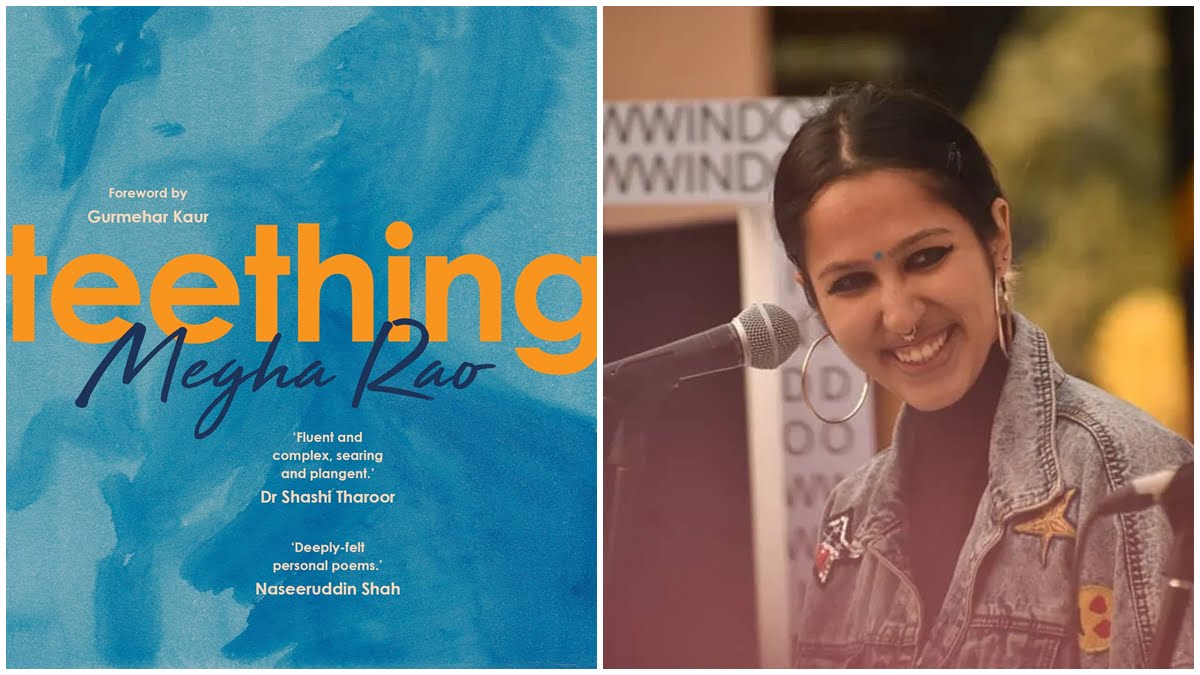

On a gloomy winter morn when the sun plays hide-and-seek for the third consecutive day in the week, the poems in Teething, written by Megha Rao and published by HarperCollins India, will bring you the sun the way early dawn rays stealthily sieve through the bedroom curtains, beseeching you to wake up and live a little more.

A Technicolour Dream

The prologue stings like a bee. Why? Because, the pain is made visible much later when you discover the swelling, inadvertently so. It is only when you see the bruise on your body that you try recalling how you got it in the first place. This is exactly what Megha Rao does in this collection. She weaves the remembrances of a past (possibly hers, albeit not necessarily) with all the warts and bruises she unravels while negotiating with her existence insofar her survival becomes bearable. As the stings and bites lay exposed like open wounds, Rao carefully and cautiously stitches a spider’s web with interconnected threads of hurt, betrayal, loss, grief, desolation, anxiety, and depression in Teething. Amid the clutter, chaos, and confusion, occasionally, there is a butterfly passing by whose flight reminds the poet (and consequently the reader) that maybe, there is a way after all to stay afloat and patiently behold what is being performed on stage like a dream in technicolour.

As the stings and bites lay exposed like open wounds, Rao carefully and cautiously stitches a spider’s web with interconnected threads of hurt, betrayal, loss, grief, desolation, anxiety, and depression in Teething. Amid the clutter, chaos, and confusion, occasionally, there is a butterfly passing by whose flight reminds the poet (and consequently the reader) that maybe, there is a way after all to stay afloat and patiently behold what is being performed on stage like a dream in technicolour.

Rao’s poetic style is both unique and relatable. The mundane realities of life find a refreshingly beautiful and poignant expression in her verses. Additionally, the reader is trapped in a whirlwind of conflicting emotions. Freedom might seem elusive but it is not completely beyond reach. For instance, when the poet recounts in ‘Coconut Oil for Trauma Wounds’ how her mother would sprinkle cologne and perfume on her and her siblings while getting ready for school, the memory paints a pretty picture but the reality is quite the opposite. Why? Because, the poet immediately surprises her reader with lines such as – “we smelled like dead flowers. Things that happy graves are made of…” Now, ‘dead flowers’ and ‘happy graves’ do not really convey unbridled joy, do they? But of course, there is a tinge of inescapable nostalgia.

Also read: Erasing Mary Shelley’s Genius From The Popular Imaginary: Fact(?), Fiction & More

Wild Verses, Tender Memories

The wilderness features abundantly in Rao’s verses in Teething. The poet borrows generously from nature’s bounty while emoting her state of mind. In this one-of-a-kind journey to the unforgotten past, the poet freezes moments of chasing dragonflies, running like magnificent wolves, brushing away crawling red ants, listening to mouthy mosquitoes, burying one’s feet in wet sand like ostriches sharing a secret, and watching either a snail lugging its home alone or the fireflies eclipsing the stars. It is almost as if the poet has, on a whim, decided to be a painter whose brushstrokes are conjuring up magical landscapes on a canvas. Interestingly, these are not still images. These images are in fact moving, telling us what it means to be alive. Every resurrected event is in motion even when unfolding within the realm of the past. This is where Rao’s poetic merit stands out. In a way, it is extremely liberating and revolting. Why revolting? Because it shows the poet’s undying will to break free from all shackles. She is determined to move on, refusing to be weighed down by adversities. The poet is unwilling to surrender to her past and instead, races to a tomorrow that can bring new promises or more challenges – she is prepared for either.

Self-worth Over Self-pity

Rao’s verses read like strong, urgent pleas. Teething implores you to stop wasting time in gathering the broken pieces of yourself and instead, the poems goad you to finding the inner wholeness that is unbreakable. To wallow in self-pity could give a false sense of melancholic comfort but it is only when you wake up and move on that you realise self-worth is superior. This constant push to envisioning an emancipatory life is what lends a feminist consciousness and sensibility to Rao’s collection of poems. ‘Teething’, the initial hiccup as we understand the term, therefore, might at first come across as an unpleasant fact of life each of us wishes to avoid and keep at a safe distance. However, once we choose to accept that teething problems are inevitable at the start of anything new and we muster enough courage to get past that, the road ahead seems less uneven and we become more confident to move on fiercely and fearlessly. Eventually, our second guesses and self-doubt lose grip on us. And that is what lies at the core of Rao’s verses – to continue living.

As far as discussing the themes of political debates, gender norms and stereotypes, homosexuality, dysfunctional families, abusive relationships, and so on are concerned, poems like ‘Beedi’, ‘Mattancherry Beef Biryani’, ‘Kochu’s Lover’ shine through. These poems begin in a matter-of-fact manner laced with ordinary mirth or seriousness but as the curtains are drawn to a close, everything that is otherwise considered ‘heteronormative’, ‘universal’, ‘natural’, ‘culturally sanctioned’ or ‘politically correct’ gets turned upside down. The frugality and brevity with which Rao manages to bust gender-related myths, patriarchal bias, and societal impositions is remarkable.

Also read: My Dark Vanessa: A Novel That Underlines The Importance Of Trusting Adolescent Survivors Of Abuse

Preservation in Performance

The fact that Megha Rao is a performance poet is evident in the way she creates a rich tapestry with her verses. Her poems are seldom obliged to strict rhyme schemes or any meter. While some verses go on for two pages, sometimes compressed within a single text-heavy stanza, leaving you gasping for breath, other poems let you sigh, relax, and pause more freely. The cacophony of the clutter in the former and the subdued whisper of the latter exude a kind of distinct musical quality that Rao’s pen(wo)manship must be commended for. While the introduction to the collection states that Rao is narrating a story in verse, Teething could well be savoured as an unending song that has been composed through various stages of life, stamped with fragments of recollections and moments preserved in the poet’s elephantine memory. Closure is a promise not granted to the reader but what sure is guaranteed is the realisation that nothing remains forever – whether it is love or loss.

Finally, the poet reminds us that whenever something goes wrong or you have a bad day, just sip on some elaichi or cutting chai or take copious swigs of your favourite filter kaapi! Apparently, it works like a magic potion. As Rao points out, which is also the crux of this coming-of-age collection, “The best thing about falling apart is that you will have the privilege of experiencing survival.” If you haven’t read Teething yet, there is absolutely no glory in delaying it any further. Buy a copy (preferably from a local bookstore!) and grab a bite…err…dive in, for the sunshine awaits!

Finally, the poet reminds us that whenever something goes wrong or you have a bad day, just sip on some elaichi or cutting chai or take copious swigs of your favourite filter kaapi! Apparently, it works like a magic potion. As Rao points out, which is also the crux of this coming-of-age collection, “The best thing about falling apart is that you will have the privilege of experiencing survival.” If you haven’t read Teething yet, there is absolutely no glory in delaying it any further. Buy a copy (preferably from a local bookstore!) and grab a bite…err…dive in, for the sunshine awaits!

About the author(s)

With over 10 years’ experience in publishing and journalism, Ipshita Mitra has a Bachelor’s degree in English Literature from Miranda House, DU and holds a PG Diploma in English Journalism from IIMC. She did her MA in Gender and Development Studies and is currently pursuing her PhD in Gender Studies from IGNOU.

She has worked with The Times of India, The Asian Age, The Quint, Om Books International, World Monuments Fund India Association, and The Energy and Resources Institute (TERI). In 2016, her short story ‘Cacophony of Silence’ was published by Nikkei Voice, a Canadian-Japanese newspaper. In 2020, her short story ‘Bohemian Sailor of the Gulf’ was published by Sublunary Editions, a Seattle-based independent publisher. The Indian Quarterly (April–June 2021) published her short fiction, ‘Kabuliwala Returns’. She writes on books, culture, environment, and gender for TerraGreen, The Hindu, Scroll.in, The Wire, Wasafiri, Firstpost, Huffington Post, India Currents, and others. She tweets @ipshita77.