Editorial Note: Being Feminist is a fortnightly column that features personal narratives documenting the emotions, vulnerabilities and innermost contradictions every feminist encounters while trying to push through various degrees of patriarchy in private, professional and public spaces.

Among the many privileges a woman in India can aspire for, I have one that is valued quite highly – fair skin. Perhaps a colonial hangover, or ingrained racism, whatever the reason maybe, the end result is, fair is lovely. As an Indian women, it is a position of privilege to be fair, because what most of us are expected to aspire for, is to be good brides. Fair brides for one, make ‘good brides‘.

Being fair in fact serves two purposes – you are pedestalised and deemed ‘beautiful’ because you check at least one box of the socially approved beauty checklist. You also escape the umpteen taunts and suggestions a brown skinned woman is subjected to like ‘apply haldi beta’, ‘don’t stand in sun beta’ , ‘don’t wear darker colours beta’ and so on.

As a ‘woke’, ‘aware’ and ‘liberal’ woman, I have made conscious efforts to understand the colorist colonial hangover that makes home inside me. Yet, I let loose when I am in the confines of my home and unconsciously partake in the same cycle of commentary upon dark skin that I so vehemently call out in the public. That is, until two months ago.

:format(jpeg)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/48508683/ColorismMexico_Final.0.0.jpg)

My sister is beautiful. She has sharp facial features, voluminous hair and a healthy body. She checks all the boxes of the ‘normatively beautiful woman’, and then some more. Except, she isn’t fair skinned. Sibling fighting, as anyone who is well versed with the art will agree, can take many forms.

Between me and my sister who is physically more powerful, faster with her murderous moves and a tongue that articulates insults at lightning speed, I have often found myself helpless, until I realised I can irk and annoy her by forming nonsensical taunts about her skin tone.

But there’s something still unsettling, in my actions in private and public and perhaps it is this difference that is linked to the space that likely influences my politics and ideology. Most of us are brought up in a highly patriarchal environment, and unriddling ourselves from it is a conscious effort we must make everyday. Am I a bad feminist for dropping the efforts I make to unlearn in public when I step back into the boundary of the home?

For me, the fight is over and the taunt is meaningless as soon as I walk out of the room. The world is back to normal. Yet for her, each taunt is an invisible struggle that she is too proud to speak of. Until one when day she said, “You are not a feminist“. I half laughed and asked why, and she reminded me of the many times I have made colorist comments directed at her.

I argued back and resorted to every method of rationalisation I could. The cognitive dissonance she underlines in my belief and action was too much to deal with. So I took a pause. I was uncomfortable with the questions she posed. Am I a colorist? I did the math and took quizzes online. I was glad the internet agrees that I am indeed not a colorist.

But there’s something still unsettling, in my actions in private and public and perhaps it is this difference that is linked to the space that likely influences my politics and ideology. Most of us are brought up in a highly patriarchal environment, and unriddling ourselves from it is a conscious effort we must make everyday. Am I a bad feminist for dropping the efforts I make to unlearn in public when I step back into the boundary of the home?

Perhaps, yes. To bring my ideology into practice every time requires a certain cognitive power, which by the time I am home is all drained out. But my sister’s lessons are an important reminder that as feminists, we are always in the making; that we are only bad feminists when we stop listening and engaging. But my conversation that day with her was not over.

As a feminist, conginitive dissonances are my biggest holdup. And as an overthinker, my biggest drainer. But as my association with the movement deepens, and as my friendship with fellow feminists evolve, I have learnt to take their advice more seriously: being kind to myself first, before I extend the hand to those around me

My sister went on to say, “You are a feminist, because you are a woman“. It is true. I am a feminist because indeed, I am a woman and the successful outcome of the movement does have implications for my success and well-being. But her rhetoric made me conscious and I slipped into the same worries, as Fleabag in Season Two.

After much pondering over whether me being a woman and hence being a feminis, makes it any less legitimate by virtue of my vested interests, my answer is No. The ethics of committing to an ideology is quite simple. You adhere to all its tenets consciously and after having evaluated its ideas as leading to a morally better and socially more inclusive society than the one you currently inhabit.

It also implies that in your association with the ideology, you do not selectively invoke your ideology only when it circumstantially benefits you. Adhering and espousing an ideology also requires you to be open to a polemic rooted in reason and rationality with skeptics and fence sitters, as much as it requires you to be in one with yourself.

I don’t think then, it makes me a bad feminist or illegitimates the cause, because I am a woman. The only thing that does take away the traction from a cause as far as the question of adherents is concerned, is unethical adherence to its contents.

As a feminist, conginitive dissonances are my biggest holdup. And as an overthinker, my biggest drainer. But as my association with the movement deepens, and as my friendship with fellow feminists evolve, I have learnt to take their advice more seriously: being kind to myself first, before I extend the hand to those around me.

Author’s note: The author does not intend to appropriate the experiences of people of colour and the trauma they are subjected to. She only hopes to underline the lacuna in preaching and practice that we as feminists often succumb to, one symbolised by the dichotomy of the “home” and the “outside”

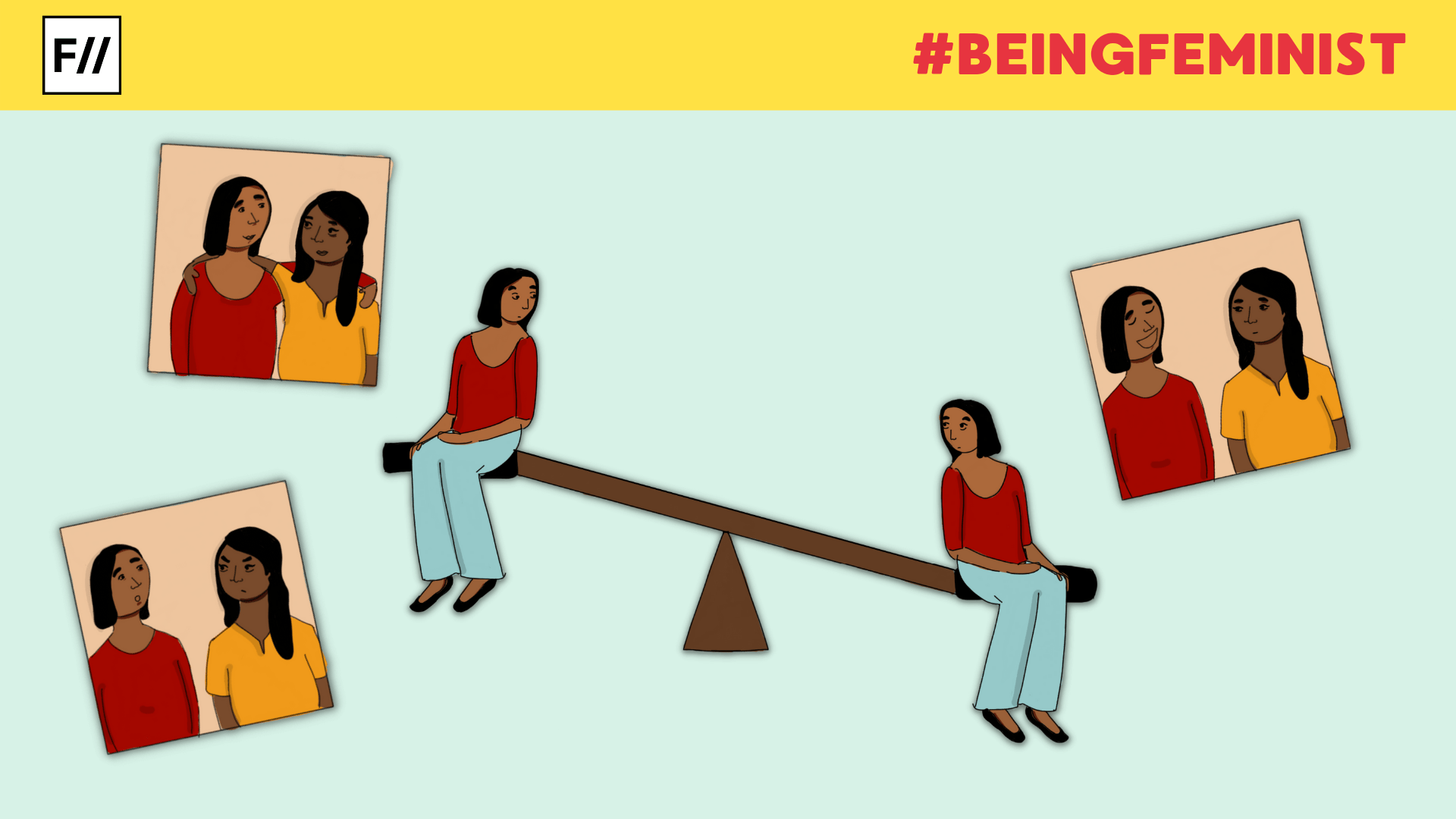

Featured Illustration: Ritika Banerjee for Feminism In India

About the author(s)

Harshita is a public policy consultant working at the intersection of gender, climate change, and disability. An alumna of Jesus and Mary College, University of Delhi, and the Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex, her work draws on her training in History and Development Studies to unpack gender as a social and structural construct.

Thanks for this thoughtful and introspective article! I’m a man who strives to be a feminist in my daily life, and some of the doubts and cognitive struggles here resonate with me (perhaps even more than they do for the author). It’s inspiring to know that such foibles and transgressions aren’t just my own, and can be transcended through effort and self-examination.