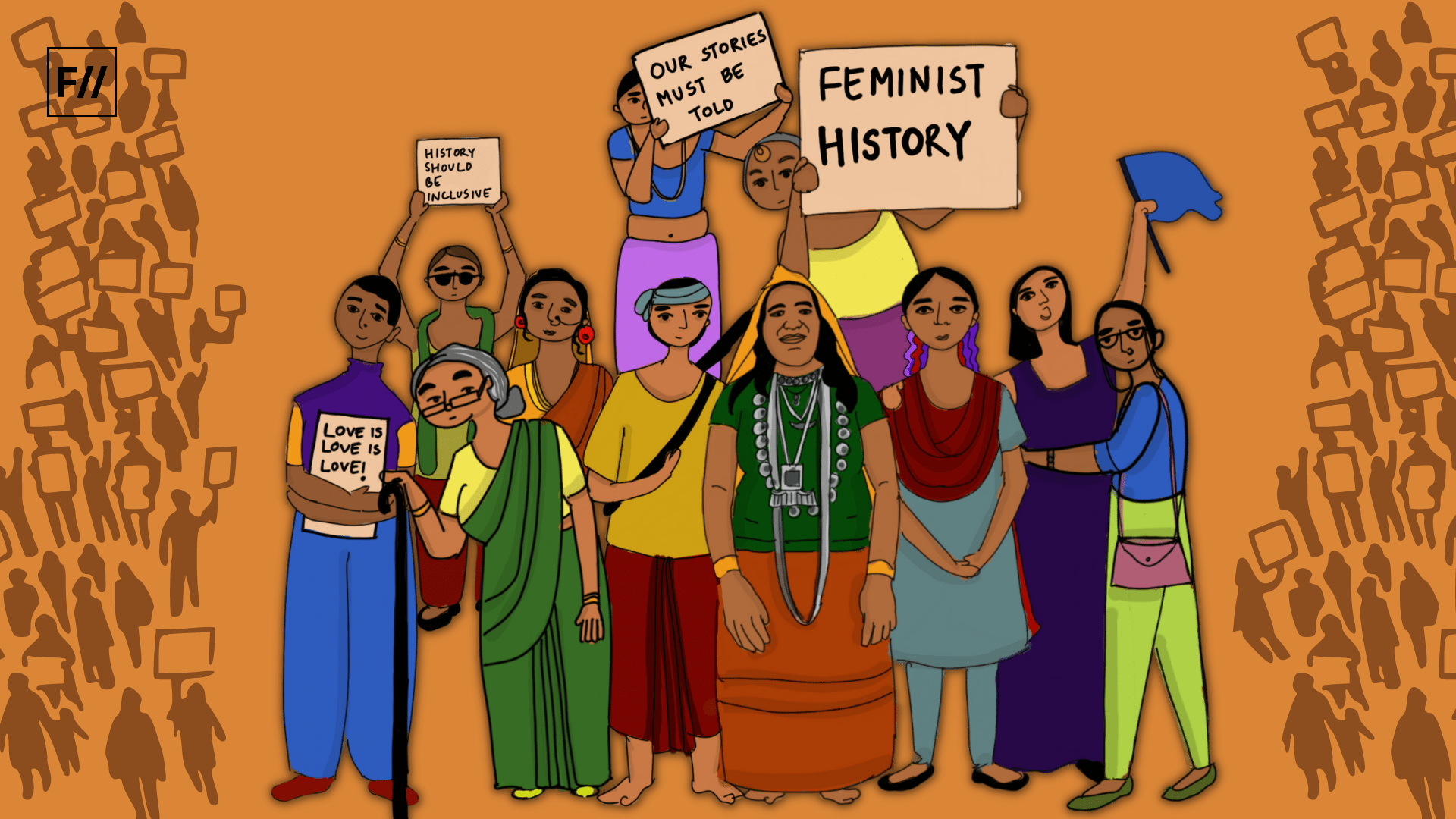

Editor’s Note: FII’s #MoodOfTheMonth for March, 2022 is Women’s History Month. We invite submissions on the contributions of women, the trajectory of the feminist movement and the need to look at history with a gender lens, throughout the month. If you’d like to contribute, kindly email your articles to sukanya@feminisminindia.com

South Asia is a sub region of Asia which includes the countries Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Pakistan, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Afghanistan and Maldives. It can be divided into a main portion (Pakistan, India and Bangladesh), an island (Sri Lanka) and two countries perched in the Himalayas (Nepal and Bhutan).

Despite a history of ethnic, linguistic and political divide, the people of the sub-region are unified by a common cultural and ethical outlook. Music, dance, ritual customs, modes of worship and literary ideals are quite similar throughout South Asia, though through centuries, the region has been divided into many-hued political patterns.

The British rule of South Asia lasted from 1800 upto World War II. As the British occupation drew on, vigorous independence movements developed. After WWII, the independent nations of the Republic of India and Islamic Republic of Pakistan (both East and West) were established in 1947. Later, Bangladesh seceded from Pakistan in 1971.

The image of Indian women during the colonial period has been of passivity, of a group silenced. Women were burdened and confined with patriarchy during the colonial period i.e. colonial patriarchy and indigenous patriarchy. On one hand, it was the ‘White Man’s Burden‘ to protect Indian women from the ‘uncivilised and barbaric practices‘ here. On the other hand, men here wanted to protect their women from foreigners.

/Madras-Army-gty-56a486ef3df78cf77282d99c.jpg)

As has been identified, for the colonial state this was part of a strategy to continue domination in the guise of ‘protecting helpless and weak Indian women‘. This also provided them the moral justification for colonial rule. While for Indian men, as historian and political theorist Partha Chatterjee points out in ‘A Nationalist Resolution of the Women’s Question’, faced with defeat and humiliation in the political and material world, they constructed their women as the repositories of all that was pure and worthy in their own culture.

However in both the standpoints, women emerge as unresisting, inert and passive objects of defining discourses – people without any authority over their lives.

Author Anindita Gosh in her book ‘Behind the Veil: Resistance, Women and the Everyday in Colonial South Asia’ has highlighted that women were discovered in assertive roles, they were either participants in larger mass struggles under the tutelage of their male peers and guardians like women activists in the nationalist movement or unusual eruptions within a conventional social fabric such as Tarabai Shinde, Binodini Das, Pandita Ramabai etc.

Gendered perspectives of partition are important because they help us to understand the unheard voices and unacknowledged experiences of women. It also makes us recognise how nation, state, family and community construct their identities through their possession of the female identity and body. How their honour and their revenge, both, are linked with the female body

The idea of resistance in everyday social life is somewhat a new one. When the subjugated and dominated were unable to openly express anger against the dominant groups, the moods of resentment and discontent existed secretly, in different forms. In ‘Domination and the Arts of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts’, James Scott describes hidden transcripts as the conscious statement of insubordination by the oppressed, made in safety among confidantes and accomplices.

They are the proof of a consciousness that has been able to escape the effects of total domination, even while scrupulously maintaining structures of deference and obedience in the presence of authorities. He points out that we might interpret the rumours, gossip, folktales, songs, gestures, jokes and theatre of the powerless as vehicles by which, among other things, they insinuate a critique of power while being forced to hide behind anonymity or innocuous understandings of their conduct.

Also read: Remembering The Vision And Resilience Of Savitribai Phule On Her Birth Anniversary

Occurrences of resistance do not always and only imply pure forms of autonomy or escape from dominant structures. There is a struggle residing every day, which can be less dramatic and less visible. As Ghosh has stressed that in treating gender as a site where power is constantly fractured and reshaped by the struggles of subordinate groups, it is possible to see this as a part of an ongoing negotiation between the dominant and the dominated to condition the material, social and political structures in which they exist.

In many ways, women experience the aftermath of conflict like the wind. In ‘No Woman’s Land’ feminist writer and publisher Ritu Menon has described the partition of India in 1947 as one of the most massive peace-time upheavals ever, and it is generally agreed that its reverberations persist and are still being felt with varying degrees of intensity, in the three countries most affected by it.

In our region, in the recent past and especially in the light of high levels of ethnic violence in the entire South Asia region, the effect is undeniable and lingering. Patriarchy is the major obstacle to women’s advancement and development. The nature of this control may differ. So it is necessary to know the system and its intersectionalties which keep women dominated and subordinate

Gendered perspectives of partition are important because they help us to understand the unheard voices and unacknowledged experiences of women. It also makes us recognise how nation, state, family and community construct their identities through their possession of the female identity and body. How their honour and their revenge, both, are linked with the female body.

This is the generality of the partition – it exists publicly in history books. The particular is harder to discover, for it exists privately in the stories told and retold inside so many households in India and Pakistan as pointed out by academic, author and feminist activist Urvashi Butalia in her book ‘The Other Side of Silence’.

Women and their experiences have always been put last in terms of priority and importance while most of the time, their lived realities remain invisible in history because women were always seen and expected to be seen within the four walls of the household, assumed to be less informed.

The opposition between the personal and the political can be demolished by reflecting the experiences of women and by proving that the personal is political. As Menon writes in ‘No Woman’s Land’, “The weak, they say, have the purest sense of history, because they know anything can happen. The weak and the powerless, one might add. Historically speaking, women, even if not ‘weak’, have almost always been powerless in the larger meaning of the word, and the question that interests us here is: how does this situation influence their sense of history? It is not usually asked of women-they are presumed to be outside history because they are outside the public and the political, where history is made.“

In our region, in the recent past and especially in the light of high levels of ethnic violence in the entire South Asia region, the effect is undeniable and lingering. Patriarchy is the major obstacle to women’s advancement and development. The nature of this control may differ. So it is necessary to know the system and its intersectionalties which keep women dominated and subordinate.

Also read: Sudarshana’s Escape & Veera’s Return: Two Stories Of Partition’s Abducted Women

Patriarchal institutions and social relations are responsible for the secondary status of women. The patriarchal society gives absolute priority to men and limits women’s human rights. There are many instances and evidence of resistance by women during the post-colonial period in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh, which must be read and investigated to see how historic events have impacted their lives in ways the mainstream does not ever acknowledge.

Nalini Bhattar is a feminist and an independent researcher. A postgraduate in Women’s Studies, she has voiced for women’s rights through her articles and poems and has contributed to Youth Ki Awaz, Women’s Web, Delhi Poetry Slam, etc. You can find her advocating equality for all, sipping chai, and turning pages of her favourite books with her dog lazing around her. She may be found on Twitter

Featured Illustration: Ritika Banerjee for Feminism In India

AIMS Academy offer ranges of professional and vocational courses in Business Studies, Accounting and Finance, Tourism and Hospitality Management, IT, and so on. We offer courses starts from RQF Level 3 to 7 that accredited by OTHM Qualification UK. Other courses are accredited by Bangladesh Technical Education Board

https://www.aims-academy.com/