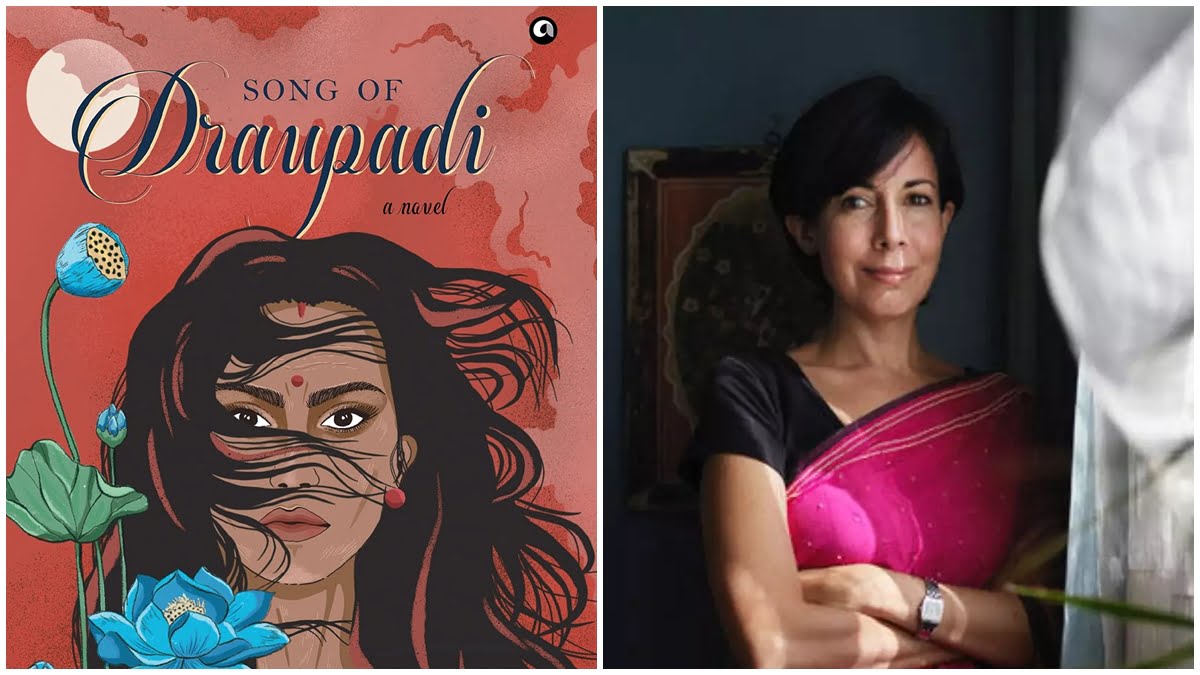

“For all the unrecorded voices, for the furious, the untamed, the dispossessed, and the voiceless, for the women of India.” — Ira Mukhoty’s book ‘Song of Draupadi: A Novel’ commences. It then goes on to say that “To anyone growing up in India, the stories of the Mahabharata form the cadence to which the seasons are set.” In eloquent English, the note establishes the upper-caste customs as the default narrative of India. And as someone who grew up in an extremely backward farming community in Jharkhand, for me, seasons were set in the chronological periods corresponding to agricultural processes named in our native languages.

Over the past few centuries, anti-caste reformers and historians have actively engaged with and written on the ancient epics. In this regard, Ira Mukhoty’s book doesn’t challenge but only re-establishes the epics. The book, though, aims to narrate the stories of the women characters; to delve deeper into their personalities, to chronicle the dilemma and dialogues they had.

Over the past few centuries, anti-caste reformers and historians have actively engaged with and written on the ancient epics. In this regard, Ira Mukhoty’s book doesn’t challenge but only re-establishes the epics. Song of Draupadi, though, aims to narrate the stories of the women characters; to delve deeper into their personalities, to chronicle the dilemma and dialogues they had. The book is well-articulated — one automatically imagines the scenarios in one’s head while reading the elaborate descriptions of grandiose jewellery or delicacies galore. However, the fictional novel again falls into weaving the so-called mainstream narrative of elite women as the default — women who have bloodlines related to the palaces. So while the chapters do dwell on the trials and tribulations faced by stately women; they do not deliberate as much on the trauma inflicted on the Shudra and tribal women; sometimes by the stately women themselves. This “giving” of “slave women” need not be celebrated or normalised.

Also read: In Search Of A Home Disappearing: Book Review ‘Sambac Beneath Unlikely Skies’ By Heba Hayek

The book elucidates on the caste system as an exchange of labour in the city without contextualising how the upper-castes exploited the Shudra communities. The incidents where the upper-castes have rebuked the Shudra individuals and families are stated blandly without them being criticised and analysed. Further, the upper-caste characters continue having an anti-tribal gaze throughout and which the book only upholds without questioning. There is a constant urge and compulsion to have more upper-caste sons and even when the book does reflect on the emotions of women, it only reimagines and reflects on the royal ones. Their feelings of diminishment and discomfort, of desire and debilitation as their lives go through displacement, war, love and losses are explicated in detail. The readers get to have an inner-view of the workings of the female quarters of the palace. While the discussion between time and chronology in the book can be deliberated upon by those engaging with the epic in this nuance; the fictional book fleshes out the characters of the women from the regal families intricately and makes them more humane and comprehensible. Furthermore, instead of pedestaling them, it rationalises their anger and wrath, it centres their yearning for revenge and not only their male-serving selflessness. The book not only focuses on what the women extend to men but also on the women themselves — the dishes they relish, the adornments they wear in their hair, the agony and the trauma extended onto them by the egos of men.

However, even as the elite women take ownership of their actions, the marginalised women continue to be owned by the regality. One doesn’t get to know the thought processes in the minds of the women workers and most elite readers in India do not bother about that either. The book ruminates about what queens and would-be queens are thinking when the women workers come to serve them but does not elucidate on the opinions of the workers themselves, or at times relegates them to a cursory glance. This literary attitude of according the least time to the emotions of those who run the empire through their excruciating labour and the perspective of taking their labour for granted; is common among elite pens and gazes in India. The labouring class is not named except in relation to labour and further, the book puts the “low-caste” woman as well as the tribal woman in bad faith. It normalises caste roles without questioning them and states instead of scrutinising the superstition of menstruation being polluting and the bleeding phase being considered the polluting time of the month. Here, the book does not contextualise the past with respect to contemporary developments.

And while Song of Draupadi is well-crafted in language and technically, quite well-written, it re-inforces the erasure of marginalised women and let alone depicting their feelings; it does not even count them or name them. In this recording of the voices of women, there is no focus on the marginalised women, in this acknowledgement of the furiousness of the Indian women, it is only the regal women who are celebrated, in this historicization of the dispossession of women, the marginalised women workers who were always dispossessed and displaced based on the geographical shifting of the queens are sidelined, and are continued to be relegated as voiceless even when the author documents dialogues amongst women.

Also read: Book Review: Time And Race in Octavia Butler’s ‘Kindred’

Even in the absence of accounts, the grievances of the labouring class can be documented by structuring them around the social reality of those times, however, Song of Draupadi does not venture into that orientation, let alone focus on their sufferings. Therefore, while this book is an initiation in a certain direction of discourse, it is only directed at the upper echelons even among those oppressed by gender.

Song of Draupadi, then, is not an apt documentation of gender and history; for the notion of limiting women’s history to royal women is against the labour and existence of the working-class women. Even in the absence of accounts, the grievances of the labouring class can be documented by structuring them around the social reality of those times, however, the book does not venture into that orientation, let alone focus on their sufferings. Therefore, while this book is an initiation in a certain direction of discourse, it is only directed at the upper echelons even among those oppressed by gender.

About the author(s)

Ankita Apurva was born with a pen and a sickle.

i loved your writting style keep up with good work Lyricswarr.in

please do visit my link below

Durga Chalisa

Durga Chalisa Lyrics

Durga Chalisa Lyrics in Hindi

Durga Chalisa Lyrics in English