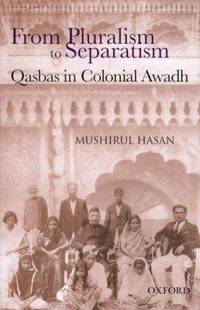

It has been almost two decades since the book From Pluralism to Separatism: Qasbas in Colonial Awadh (2004) by Mushirul Hasan was, published and yet we see that its core argument stands not only relevant today but also demands further investigation. Hasan argues that one must study pluralism to understand what goes into the making of composite culture.

Pluralism was the hallmark of qasbas which were much more culturally refined than cities and villages. The book lays emphasis on studying relationships and interactions over differences and distinctions. It tries to capture the fine textured stories of families and friendships that dotted the qasbati life of the Lucknow region between 1850 and 1950.

Individuals, their families, their towns, and their socio-cultural milieu are all weaved neatly to form a narrative of Islam, culture, society, and polity, that together present the real life experiences of the time. The discourse of gender justice among the Awadhi Muslims during the colonial times is also well reflected in the book.

The book suggests that the Urdu elites showed a deep sensitivity towards the ‘women’ question. With changing circumstances, one could sense that their thought process got influenced by colonial modernity and theological debates within Islam. For example, a resident of Bilgram, Maulvi Muhammad Zahiruddin, published Mufidun niswan, where he argued how the Quran and Prophet’s own life showed Muslims that education must be undertaken by women.

The case of Meer Hasan Ali is more fascinating. She was a British Christian lady married to a Shia in Lucknow. Talking about her experience during 1830s, she was happily surprised to see Lakhnavis receiving her without prejudice and allowing her to practice her European habits and Christian customs.

Hakim Ajmal Khan established a women’s section in his Yunani and Ayurvedic College in 1909. All these efforts could not usher in societal changes but created a discourse that women, just like men, deserve modern education and employability. No doubt far more men undertook higher education than women and by early twentieth century, qasbati men were getting modern education across India

It might have been a matter of moral piety (akhuwat) for the qasbati men. Islam was just one among the many factors influencing qasbas, something which many serious historians fail to grasp. Meer Hasan Ali herself was aware of this; and so was Choudhary Muhammad Ali (1882–1959). Choudhary Muhammad Ali was a Shia landlord based in Rudauli qasba and a close friend with the (Sunni) Kidwais of Masauli qasba. Ali not only criticised regressive people opposing modern education for girls, but also criticised madarsa curricula and gender segregation.

Choudhary. Muhammad Ali’s four daughters studied in a Muslim girls’ gchool which was founded by Saiyyid Karamat Husain in Lucknow. Sirajul Haq, Rudauli’s first graduate, was asked to do the same. These ideas were also present in the writings of Niyaz Fatehpuri published in Nigar in 1932 and in Gahwara-e tamaddun. Karamat husain’s girls’ School received donations from the Raja of Mahmudabad who also patronised MAO college and other progressive activities. Such anecdotes are interspersed all over the book.

Also read: The History Of The Colonial State And The Unmaking Of The Tawaif

Altaf Husain Hali (1837–1914) published Chup ki daad (voices of silence) in 1905. Ahrauli’s landlord Saiyyid Muhammad Baqar supported girl’s education. Abdul Halim Sharar critiqued purdah in his newspaper Parda-e Ismat; so did Sajjad Hyder Yildirim (1880–1943),

an Aligarh graduate.

Sharar and Yildrim were influenced by both English and Turkish writings. Their commitment intruded those spaces which are usually meant for refreshments. We find Yildrim talking passionately in favour of women’s education at the annual dinner get-together of the Aligarh Old Boys on 7 April 1912. Among the attendees were Wilayat Ali Kidwai, Ross Masood, Ali brothers Shaukat and Mohammad. Abdur Rahman Bijnori started Sultania College for women in Bhopal while his friend Saiyyid Mahmud, a contemporary of Nehru in Cambridge, collected funds for women’s education.

From Pluralism to Separatism: Qasbas in Colonial Awadh elaborates on how the qasbas in colonial Awadh were vibrant and composite culture defined the qasbati life. Feminism, socialism and nationalism all rubbed shoulders with one another. It has beautiful descriptions of Sufi shrines and Muharram rituals and how Hindus celebrated Muharram across castes

Hakim Ajmal Khan established a women’s section in his Yunani and Ayurvedic College in 1909. All these efforts could not usher in societal changes but created a discourse that women, just like men, deserve modern education and employability. No doubt far more men undertook higher education than women and by early twentieth century, qasbati men were getting modern education across India.

According to historian David Lelyveld (Aligarh’s First Generation: Muslim Solidarity in British India, 1978) almost half of the students in M.A.O. College between 1875 and 1895 came from qasbas. Mubashir Hosain Kidwai, studied at Trinity College, Cambridge and went on to become a judge of the Allahabad High Court in 1947.

Modern education gave confidence to Muslim men to sustain pluralism. Women joined them slowly and gradually. Wilayat Ali’s only daughter Anis Kidwai is one such example. In 1928 she wrote her debut article in Ismat, a feminist magazine and in 1947 she published her debut book. Two years later Azadi ki chhaon mein (In the Shadow of Freedom) was published based on her experiences during the partition. It is extraordinary how in so small a qasba so many women made the break with tradition to choose a career for themselves in politics, education, and creative writing.

From Pluralism to Separatism: Qasbas in Colonial Awadh elaborates on how the qasbas in colonial Awadh were vibrant and composite culture defined the qasbati life. Feminism, socialism and nationalism all rubbed shoulders with one another. It has beautiful descriptions of Sufi shrines and Muharram rituals and how Hindus celebrated Muharram across castes.

Mushirul Hasan must be applauded for writing on how studies on pluralism should be promoted to know how and why human cultures lived in harmony. Women’s subjectivity and inter-community marriages can be important lines of enquiry for further research on pluralism.

Also read: Urdu Women’s Magazines: The History Of Publications That Pioneered Gender-Based Discourse

Zeeshan Husain has done BSc (AMU), and MSW (TISS). He is presently pursuing PhD in sociology from JNU. His research interest is in the society and polity of Uttar Pradesh

Featured Image: Madras Shoppe