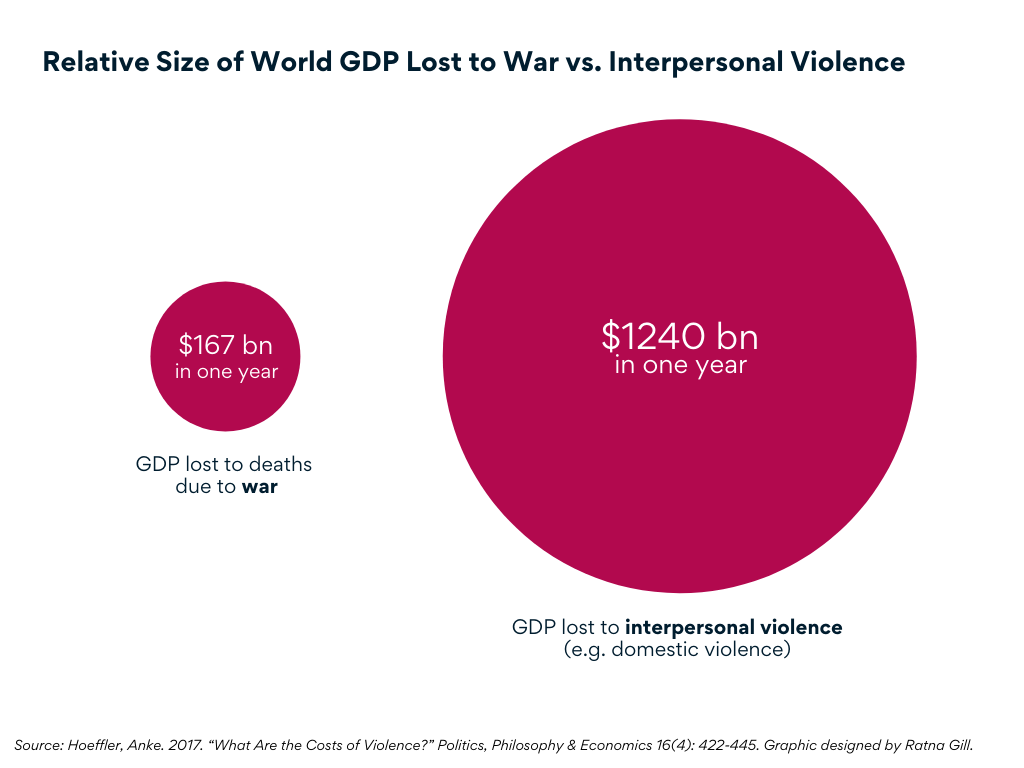

India is engaged in a heated debate about whether to make marital rape illegal. Far from criminalising the act, the section of India’s Penal Code on sexual offenses specifically calls out marital rape as “not rape.” It reads, “Sexual intercourse or sexual acts by a man with his own wife, the wife not being under fifteen years of age, is not rape.” And yet, we know that “the most common form of violence that women experience is from an intimate partner” and 30 percent of women above age 15 around the world have experienced physical and sexual partner violence. In fact, around the world, the cost to world GDP of deaths due to interpersonal violence is ten times the cost of deaths due to war in a year. And this is not taking into account the personal loss faced by the perpetrators of violence.

Also read: Karnataka High Court’s Progressive Verdict On Marital Rape Comes As A Ray Of Hope

With economic instability increasing due to the war in Ukraine while COVID-19 remains prevalent in much of India, special attention should be paid to the impact on victims of sexual violence. As India faces a widening trade deficit, higher inflation, and the weakening of the rupee, heads of households are likely to be hit by the economic burden. And research shows that in highly patriarchal cultures, men who feel their masculinity and/or sense of control is threatened, are more likely to respond with violence.

As India faces a widening trade deficit, higher inflation, and the weakening of the rupee, heads of households are likely to be hit by the economic burden. And research shows that in highly patriarchal cultures, men who feel their masculinity and/or sense of control is threatened, are more likely to respond with violence.

In a 1996 study by Dov Cohen et al., men in two groups were treated with a “slight” to their masculinity (e.g. being pushed in the hallway on the way to the study room). Those in the treatment group, who came from a more patriarchal society, were more likely to express hostility after a perceived threat to their masculinity. Participants from a more patriarchal society were angrier at the “insult,” used more hostile language in a sentence completion exercise they had to do after the hallway encounter, and exhibited levels of cortisol 79 percent higher than their initial level. They were also more willing to engage in a show of strength (e.g. punching something or volunteering to get an electric shock) after they had experienced the minor “threat” to their masculinity. This study raises concerns for the impacts of increased instability on incidents of interpersonal violence in India, a highly patriarchal society.

During the first month of the COVID-19-spurred lockdown in 2020, data revealed an alarming surge in reported cases of domestic violence: women in India were 17 times more likely to be assaulted by their spouses during the lockdown. Non-profits hypothesised that this was due to frustration faced by men who lost their jobs, were unable to leave the home, and may have relied on alcohol or drugs as coping mechanisms. Being a “strong” primary breadwinner who provides for one’s family is a key component of how we as a society define masculinity, and men’s weakening ability to do that could lead to increased incidence of acts of aggression at home.

Would criminalising marital rape alleviate this issue? Not by itself. But making illegal an extremely violent and psychologically damaging act that many women take as a given would give some women the tools they need to exit abusive relationships. “Men’s rights” activists around the country are scared. They argue that “making nonconsensual sex a criminal offense would be tantamount to turning husbands into ‘rapists’ and will lead to the breakdown of the institution of the family.”

Unpacking where that fear comes from is key to understanding the resistance coming from men. Unpacking notions of family, informed by commonly held beliefs around the roles of people of different genders, will be important to move the conversation forward. Alongside criminalising marital rape, education initiatives that allow Indians, regardless of gender, to explore their notions of “what it means to be a man” or “what it means to be a woman” in more depth are desperately needed. Most programs that address gender issues in India are targeted at women and girls. Programs that do exist for boys are more aimed at “teaching boys not to be violent” than allowing boys and men to explore a more expansive, compassionate masculinity. Boys are not inherently violent. Something about our culture makes them act that way, and we need to grapple as a society with what that is.

We desperately need to start conversations with children from a young age—boys and girls and those of other genders—about what it looks like to address emotions in a healthy way, respect others, and love and honor ourselves. If parents, teachers, counselors, and social workers can be supported to have those conversations effectively, hopefully one day we will live in a world where we don’t have to think about marital rape. In the meantime, making it illegal to have sex with your partner without her consent is an urgent first step.

Also read: Marital Rape: The One That Cannot Be Named

Initiatives like WeUnlearn and the BoyTalk Project have started to do just that. We desperately need to start conversations with children from a young age—boys and girls and those of other genders—about what it looks like to address emotions in a healthy way, respect others, and love and honor ourselves. If parents, teachers, counselors, and social workers can be supported to have those conversations effectively, hopefully one day we will live in a world where we don’t have to think about marital rape. In the meantime, making it illegal to have sex with your partner without her consent is an urgent first step.

Featured image source: Aasawari Kulkarni/Feminism In India

About the author(s)

Ratna Gill is a Harvard grad passionate about rights for women, children, and people of color around the world. Follower her on Twitter at @Ratna_Gill.