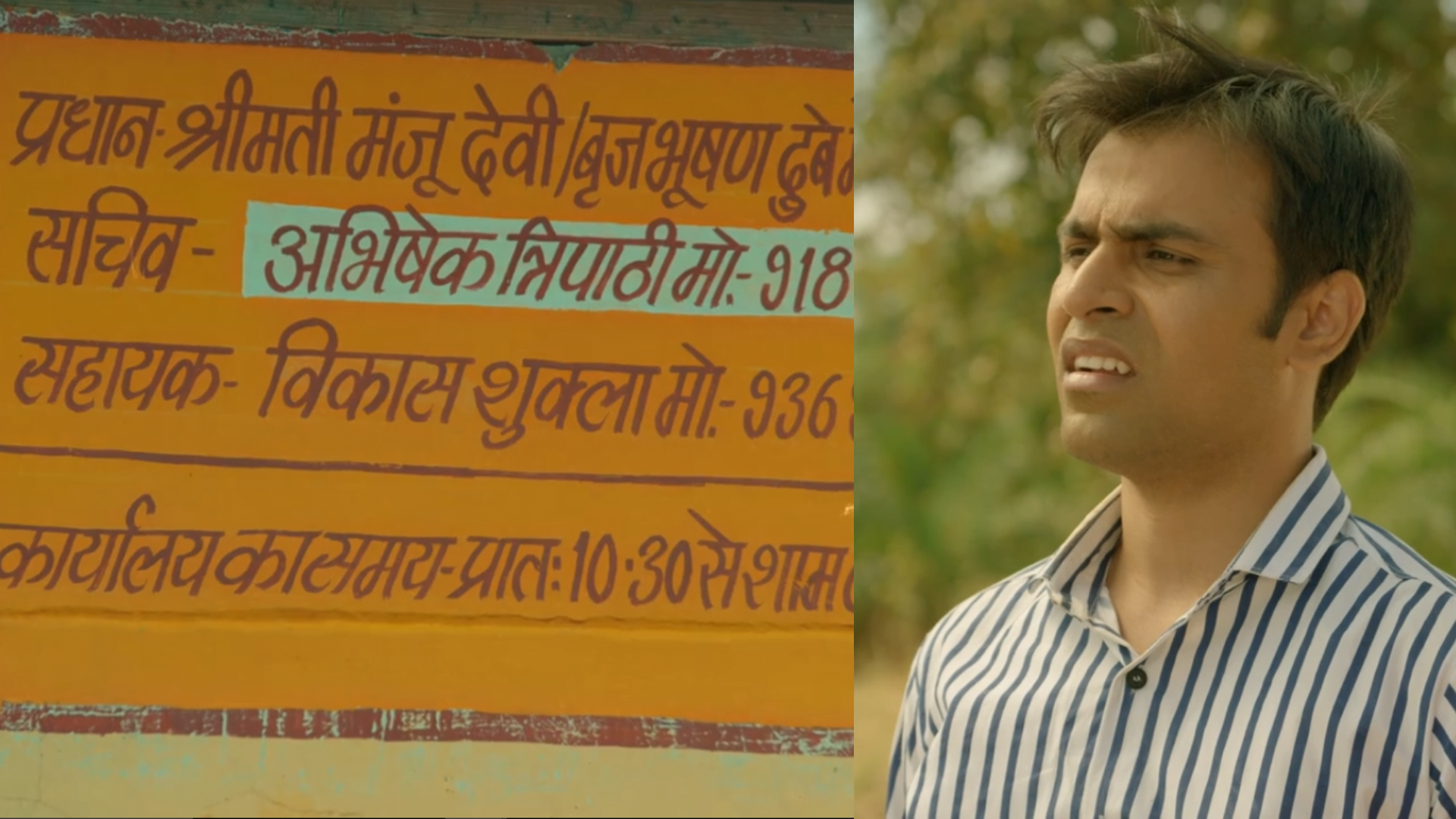

At the beginning of every episode of both the series of Panchayat, you find a board hanging outside the local government office stating the names of the officials—they have the surnames Dubey, Tripathi, and Shukla—all Brahmins. Immediately in every episode, enters another official with the surname Pandey, another Brahmin. Therefore, not subtly but rather staunchly, this board epitomises the crux of the show, whose plotline goes from one Brahmin to another. In this regard, the series is quite diverse. It has tried its level best to have adequate representation — of Brahmins.

In the first season, it was established that Panchayat is based in a village in Uttar Pradesh — the breeding grounds for casteism. The local office is disproportionately controlled and dominated by Brahmin men, and even when the government reserves seats for women candidates, the Brahmin men regain power by making mannequins out of their wives, who then win the seats. And then comes the “outsider” in the local rural office — Abhishek Tripathi — an urban boy who has been posted in this village. Tripathi is an outsider to the rural area but is, of course, from inside the Brahmin community. This was paramount for the show to even exist. From the day he lands in the village, the Brahmin officials take Tripathi for walks, invite him for dinner at home and plot his marriage with their daughter — things possible only because Abhishek is a Brahmin.

In the first episode of the first season, as the Brahmin Pradhan or more accurately, the self-appointed Pradhan Pati loses the key to the rural government office; he is told by other Brahmins, including his wife Manju Devi, who is technically the Pradhan, that he should have kept it tied to his Janeu — the caste-pride symbolising thread that Brahmins wear. This suggestion, both physically and metaphorically, demonstrates that the key, access, and power to the rural government office are tied to the Janeu, which everyone entering the office carries.

In the first episode of the first season, as the Brahmin Pradhan or more accurately, the self-appointed Pradhan Pati loses the key to the rural government office; he is told by other Brahmins, including his wife Manju Devi, who is technically the Pradhan, that he should have kept it tied to his janeu — the caste-pride symbolising thread that Brahmins wear. This suggestion, both physically and metaphorically, demonstrates that the key, access, and power to the rural government office are tied to the Janeu, which everyone entering the office carries.

Since the first day itself, all the Brahmin officials support Abhishek Tripathi in his work and invite him to hang out when he is low. One wonders what would have happened if an individual from a minority community had entered Abhishek’s position. In her Sahitya Akademy Award-winning book ‘Coming Out As A Dalit’, Yashica Dutt elucidates on how upper-castes purposely mark SC, ST, and OBC candidates less in interviews, deliberately punish or disobey them on duty and heckle them for rightful promotions. Another glaring example of the same can be seen in their grotesque opposition to the Mandal Commission Report which had shown that OBCs are the least represented community.

Abhishek Tripathi hates his job and considers his salary of INR 20,000 per month to be below his stature. However, for any marginalised community person, that meagrely-paid job would most probably be a way to get out of years of oppression. The paper titled ‘Wealth Inequality, Class and Caste in India, 1961-2012’ states that SC, ST, and OBC caste groups earn 21, 34, and 8 per cent less than the national average and that Brahmins earn 48% above the national average, owing to a casteist nexus at the place.

The pandemic has only exacerbated this further. The Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE)’s Consumer Pyramids Household Survey (CPHS) database manifests that the proportion of employed upper castes decreased by seven percentage points between December 2019 and April 2020, and the corresponding fall for SCs, STs, and OBCs was exceedingly high at 20, 14, and 15 percentage points. Hence, Abhishek Tripathi experiences “problems” defined as “problems” specifically by the Brahmin community.

Throughout the two seasons, one notices Brahmins. They are everywhere. The director, the executive producer, the creative director, the associate creative producer, the assistant directors — and wait, when you would watch the end credits, you would notice that the nameless passers-by in the episode are also credited with their Brahmin surnames.

Only when the show has to depict itself in roles that Brahmins look down upon and do not want to associate with themselves, such as a marginalised man without a washroom, a politician who is a goon, a dancer, and a lovestruck but drunk auto driver — have the characters not been explicitly given Brahmin surnames. Among these cases, the powerful politicians’ economic aspirational status has been given a seemingly Thakur surname, and the destitute auto driver whom no one wants to end up being and whom Abhishek is uncomfortable with sleeping on his bed has been purposely given an OBC surname.

In the socio-economic climate of Uttar Pradesh, the women of the Nat community, a Scheduled Caste community, tend to perform on stage for meagre wages with no safety and are often at the end of violence and harassment from the upper castes. However, in all of these three roles, the dancer, the driver, and the politician have been performed by Brahmins in the show. But the show isn’t over yet. When the dancer needs some medical dressing after a scene of transphobia whose anti-LGBTQIA+ remarks haven’t been critically engaged within the show, Abhishek Tripathi, is cajoled by a bunch of corrupt Brahmins to drive the dancer to a nearby dispensary. The dispensary itself is named after another Brahmin doctor with the surname Tripathi. Throughout the show, one doesn’t meet minorities.

All across the two seasons, the show continues to be based in a Brahmin world and perpetuates an infantilising, misinforming, sexist, casteist, upper-caste urban gaze on rural India. The sheer apathy and obstinate paucity of accountability that Abhishek Tripathy has towards rural India is an exclusive characteristic of privileged surnames such as his.

All across the two seasons, the show continues to be based in a Brahmin world and perpetuates an infantilising, misinforming, sexist, casteist upper-caste urban gaze on rural India. The sheer apathy and obstinate paucity of accountability that Abhishek Tripathy has towards rural India is an exclusive characteristic of privileged surnames such as his.

In the show, the Brahmin officials wrongfully decorate and misuse the rural school and government offices for their personal functions. If local government offices indeed run under the absolute control of Brahmins who use them for their wedding parties and where they and their relatives and friends stay, carry rifles, store and drink liquor, and then carry office chairs for personal use at their homes, then one can be sure that these Brahmins consider government property as their personal property. And one can most definitely be sure that reports of caste-based crimes would not be registered, let alone be penalised.

The ease with which the characters gel along is more because of the commonality of caste and less because of the presence of conscience towards the constitutional functioning of the local government office. Vishwanath Chatterjee and Abhishek Pandey play the sub-inspectors, Jayshankar Tripathi plays the head constable, Deepak Kumar Mishra plays the electrician, and even the father who wants to get his son registered is named Deenbandhu Pathak, while Jyoti Dubey plays the mother. The actor against whose name the Pradhan is mocked is Mithun Chakravarty.

As the episodes go on, the Brahmins mockingly tell the milkman to bathe, and even when the BDO calls someone on the phone, it invariably has to be a “Tiwari Ji”. When the two Brahmins in the office, the UP Pradhan and the Sahayak with surnames Pandey and Shukla, stop vehicles to collect contributions for the Akhand Ram Paath, the bus conductor is asked his name, and he replies, “Prajesh Mishra”. Meanwhile, the end credits of the episodes range from Chakraborty to Tiwary to Sharma to Jha to Chatterjee.

In the show, the Brahmin officials wrongfully decorate and misuse the rural school and government offices for their personal functions. If local government offices indeed run under the absolute control of Brahmins who use them for their wedding parties and where they and their relatives and friends stay, carry rifles, store and drink liquor, and then carry office chairs for personal use at their homes, then one can be sure that these Brahmins consider government property as their personal property.

Through false objectivity and fabricated universality, Panchayat laughs at sexism and upholds casteism. One can see a visible difference between the house of the Pradhan Brijbhushan Dubey and the other houses of the marginalised who have not been mentioned by their social location nor has the cause behind this paucity deliberated upon.

Even in the instance in which Abhishek encounters a destitute man at the grocery store, who has not been paid his rightful wages due to the inefficiency and corruption of the so-called meritorious Brahmin council, Abhishek is comfortably apathetic and reluctantly involved in his government role. The Brahmin Pradhan has sacks of rice, litres of milk, and other riches at his house, way more than his family of three can consume even as the destitute man doesn’t even have INR 30 to purchase or rice to barter vegetable oil for cooking vegetables in his house leading to his child being unable to eat. The shopkeeper even has the audacity to direct the man to stop eating oil the way rich people are curbing its consumption. Systemically induced hunger cannot be compared to wilful zero-figure dieting. Only zilch conscience can draw such fundamentally baseless parallels.

Abhishek Tripathi mocks rural accents and flows with the corrupt, inefficient system. He chills about patriarchy, barring a couple of self-eulogising incidents where even as the women fight the battle, he is made the hero. The collective conscience and intelligence of any culture or individual can be gauged by the art it considers to be enjoyable and entertaining. Urban upper-caste viewers identify with this show terming it as a comedy because they identify with the same evasiveness and wilful unaccountability that Abhishek Tripathi has. All their lives, they have exploited rural people without even acknowledging their presence. And throughout the two seasons, again, the credits of the movie go from Chattopadhyay to Rao to Iyer to Desai to Deshmukh to Dwivedi.

In the second season, when Brahmins sell the mud extracted from the village in a corrupted manner, the mud rates are deliberated upon with a Tripathi, and the brick kiln owner then receives calls from some “Panditji” to whom he will give bricks.

The female representation of the show is solely upper caste and upper-class women who do not extend the marginalised any respect. The series touches on the demeaning regionalism perpetuated by those who use the more self-assigned superiority-inducing “Main” on those who say “Hum” — both alternatives are used to refer to the self. Yet, the BDO office is again inundated with Brahmins on calls as well as nameplates, as the series normalises and, in fact, romanticises songs being played as women cook and men chill. Even when the Brahmin Pradhan’s family goes to meet a pathetic and prospective groom for their daughter, the groom’s father is referred to as “Pathak Ji,” indicating absolute caste-based endogamy.

When the Brahmin Pradhan Braj Bhushan Dubey, technically Pradhan Pati, faces opposition from rivals who question his corrupt practices in the second season, the opposition comes from another Brahmin, Bhushan Sharma, whose ego gets hurt. The idea that the marginalised can also question the system does not cross them.

The collective conscience and intelligence of any culture or individual can be gauged by the art it considers to be enjoyable and entertaining. Urban upper-caste viewers identify with this show terming it as comedy, because they identify with the same evasiveness and wilful unaccountability that Abhishek Tripathi has. All their lives, they have exploited rural people without even acknowledging their presence.

And when Abhishek Tripathi’s friend Siddharth comes to the village, the Brahmin Pradhan listens to his first name, and then probes further, saying, “I understand your name is Siddharth. But tell me your full name.” The pradhan’s desperation knows no bounds when he learns that Siddharth only has his first name on his certificate, too. He then asks for Siddharth’s father’s name, to which also Siddharth replies with the first name. It is then that Abhishek Tripathi intervenes and mentions Siddharth’s family surname ‘Gupta’, that the Pradhan Braj Bhushan Dubey is relaxed and refers to him as “Gupta Ji.” The entire upper-caste group then hangs out together and asks Siddharth to join as well.

One wonders what would have happened if Siddharth was not an upper caste. Would he have been offered tea next, would he have been asked to leave, would he have been offered to sleep in the Brahmin pradhan’s house at night. But this intersection has been evaded and not dealt with. This upper-caste show doesn’t believe in bothering about how eighty per cent of the population would have been perceived and the kind of life the caste system forces them to live every day. In a later episode, when the other Brahmins remind the Brahmin Pradhan about Siddharth, the Pradhan is unable to recall him, and when he finally does, he refers to him as “Gupta Ji” and not as Siddharth. His caste is his sole identity.

Panchayat reinforces casteism under the cruel cloak of humour for the privileged. Linguistic commercialisation has been used to modify laughter — a tool of expression — into a tool of brutality. One is brought with ease with casteism; one is made comfortable with only Brahmins abound.

Panchayat reinforces casteism under the cruel cloak of humour for the privileged. Linguistic commercialisation has been used to modify laughter — a tool of expression — into a tool of brutality. One is brought with ease with casteism; one is made comfortable with only Brahmins. Meanwhile, Raveena, Rinky’s friend, is played by Aanchal Tiwari. Rajkumar Bhaiya is played by Anup Sharma, the ward member has the surname Chakraborty, and again, the credits roll with surnames such as Kulkarni, Tiwari, Dubey, Pandit, Pathak, Mishra, Pandey, and Joshi.

Of course, upper-caste critics, whose idea of India is purposely limited by their experience of elite, egocentric circles, are praising the TV series. That the upper-caste critics are praising this show itself is proof of the casteism perpetuated by the show under the mask of humour.

Even in death, there is caste, and the movie evades any discussion on it. Meanwhile, the credits again go from Tendulkar to Bhattacharjee to Trivedi to Sharma to Jha to Upadhyay to Pandey.

In the very first scene of the first season of Panchayat, as soon as Abhishek Tripathi enters the village, the Brahmin Pradhan Brijbhushan Dubey wholeheartedly welcomes him, telling his wife Manju Devi, “Most important thing; he is from our caste“. One wonders if the creation of the show was done along the same lines.

Also read: Casteist Instagram: ‘Influencers’ Create Content Deriding Domestic Workers

Featured Image Source: Amazon Prime

About the author(s)

Ankita Apurva was born with a pen and a sickle.

Is it really necessary to bring caste everywhere?

Can’t people just appreciate the content and quality of this?

Yes ofcourse it is important to criticize in castism angle. And no one complaining about the quality of contant and art that is fantastic.

Awesome. Thanks for the article. This is an eye opener…

I’m from South. I cheered for the series without knowing how deeply it is infested with caste.

But they can not take such series with caste pride in Tamil. Thanks to Periyar and his ideologies. We don’t add surnames behind our names. We have only first names. So noone knows who belongs to which caste.

I think this is the first step to get rid of caste system.

Why bring a caste angle to this? It was a nice show and even a Brahmin like me didn’t really notice the caste angle until you pointed it out. Just stop unnecessary criticism and take a chill pill

Very good Analysis.

Wow..i did not care what caste or race or religion was shown in the show. All I cared was that it was a subtle show showing a rural India and a refreshing series above all. If u complain about castism then they don’t represent muslim , Christian, or anyother religion.in that case Tarak Mehta ka ulta chasma too is very biased. All o want to say is watch a show for it entertainment purposes.. and not dissect it in terms of caste or religion.

Of course, Taarak Mehta Ka Ooltah Chashmah is biased, apart from stereotyping and making fun of different cultures, patriarchy shown in it becomes intolerable once you begin to notice it. There is no working housewife it its society, while Bhide is unsympathetically trolled by the members over not going out for work. Its female characters are shown to follow ideal patriarchal roles happily even if they are verbally abused by their ‘Pati Parmeshwar’. Daya and Jethalal are both uneducated, still Jethalal is shown as self-taught wise businessman while Daya is very often denounced for her illiteracy, diminishing her self-confidence and limiting her wisdom and knowledge to ‘totkas’. Though the show was funny but now it is like a guilty pleasure to me, I feel guilty for laughing at its sexist and stereotyping jokes. There is no doubt about its biasedness, you can write a book about it.

Truth to tell, I belong to the lower caste, but in the more privileged middle class section, and I loved the two seasons of the show. I did notice all the facts highlighted by the author — poor not having oil for many meals, apathy of the administration towards their plight, caste references by Pradhan and others, women relegated to the margin, etc — but I looked at them as simply mirroring what is prevalent in our society, without making the hero tackle them as a ‘hero’ is expected to. Yes, the show could have addressed some social issues and I hope it does in its subsequent seasons.

Why is it neccessary to bring caste everywhere? Can’t we live without that. It’s an excellent webseries can’t we appreciate that.

Cast system exist in rural India and that is a fact, but I don’t think, one should mind If the Brahman are shown in the show, they have always been portrayed as villains in last many decades of Indian cinema.

Good analysis

I am from UP, I can tell you that in uttar pradesh generally a village will be from single caste. This just happen to be a Brahmin village, that is it. In my village everybody is Yadav.

One more reason to like this awesome series . Thanks for pointing it out Ankita !

I find it laughable and absurd, with all these comments whining about “why bringing caste in this”. Maybe, if India was a more equitable place and the Brahmin-Bania community did not own majority of the industries and by extension the country. Leaving, mere scraps for the productive castes. Then this question would be valid.

Tbh, as a South Indian. I really did not know caste surnames in the north were this obvious and in your face. Here, its much more difficult to determine one’s caste just by the name.

Indians are just not comfortable to have honest conversations regarding caste but will only marry in their caste, will treat parasite castes differently from productive castes. All the while claiming to be “anti-caste”.

Many people are replying with a ignorant tone “is it necessary to add casteist perspective”

My answer to these dumb heads would be – “If the society doesn’t recognize caste and treat every surname anonymously then this issue wouldn’t be of concern but, since people (most of us) see human beings through the goggles of caste, it is obvious to show homogeneity of surnames/castes in webseries/films to promote non-casteism.” Even if non-brahmin surnames were used in this webseries, it would have entertained people to the same degree but “Alas! People from non-brahmin castes just doesn’t qualify for being showcased; leave aside sc/st/obc community” ….this also shows how crooked & wicked & selfish had the thoughts of the makers been that they couldn’t even think of other caste surnames (either intentionally or unintentionally) …. I’m from general caste but still I condemn & criticise such supremacy-sown attitudes of these “so called brahmins”…. Probably India needs chain of B.R. Ambedkars in every generation to survive in this brahmin-bogged society… ‘actually these brahmns are white skinned britishers in disguise, came from the steppe the are trying to dominate ancient Indians who are of dravidian origin’…had even more to say but can’t type anymore

For me as a South Indian, I couldn’t find the difference between Tripathi, Pandey or Gupta..I liked the simplicity of the story and it was refreshing to watch. There are millions of people like this who liked the movie for what it is and most of them are from North Indi(who know these caste surnames very well). But I am amazed that the author couldn’t any positivity from this series(since it is mentioned as ‘Review’). This sounded more like, the topic is Brahmin bashing and the author found the perfect cause for it.

Hi Ankita , you have written a very good article regarding the single caste monopoly shown in the series… As a cinema lover and a critic I appreciate your effort regarding this topic… But , I would like to tell you that I live in Uttar Pradesh and because I belong to a rural area (and ofcourse I have seen more villages other than mine) , hence I can assure you that village system in Uttar Pradesh (or I think in other part of this country also) is very sharply divided by the hierarchical system . In simple , from the very beginning people from same caste decided to live close to each other for the cultural security and there belives and practices . So , the upper caste like brahman , thakur , bhumihar etc lived in the same village and the lower caste (or Dalits) lived in the other since the beginning . Now in the 21st century , many villages of India are now taking a form of heterogeneous society , where you can find different castes living in the same village . This was due to the process of what we know as sanskritisation . But now also there are many villages that have a majority of a single caste . Some villages are of Yadav majority , some of dalit majority and some of Brahman majority .

Hence the village shown in the series Panchayat belongs to the village of Brahmin majority . The makers of the series wanted to show the real rural society of India and that is why the Pradhan, Up-Pradhan , and the Sachiv belongs to the similar caste . The makers of the series did not wanted to show a caste as a dominating caste and other as an inferior caste . They just wanted to make a series which shows the reality of rural India and which should be family friendly . So they did .

Hence , what I think is that you should not criticize any artwork if you are not aware of the reality . Be a good blogger Ankita . Show the reality other than making a propaganda . Be responsible . You are the future of India and if you write this kind of articles than it does not make you a wise critic .

Thank you

Best of luck for your future Ankita .👍🏻😊

I absolutely agree with you. Coming from a village in Bihar, I know for a fact that the show just reflects the reality. So Ankita, in the words of Manto, “if the society is not ready to see the real happenings of the society, then the society itself is not tolerable.” Similarly, if you want such shows to incorporate better social themes, then make it happen in the society first. Art is just a reflection of the society in which we live. Hope you understand.

The show is a mere reflection of the environment of society we live in. All the actors are not Brahmins and they are merely acting to the script.

The author may simply chose to ignore the show not liked and simply enjoy the likeable ones as per the taste. No one is forced to watch the show. You don’t like it, don’t watch it.

The show is for entertainment and it ends there. The idea is not to question the show but to question the reality in which we are living and if possible attempt to bring a change. Mere criticism to an entertaining show will serve nothing…

Those from south india preaching about how prevalent cast system is in North India and how south india is above that please refer to this article this my give some knowledge to you and for whosoever wrote this article you theory is a little but too much you have streched the thread too thin , first time reading an article I felt sheer waste of time rather then enjoying the series for what it is i.e a subtle depiction of the rural India and turning it into some kind conspiracy theory . Please refrain from writing such articles it is a humble regular reader of this page.

This is the link for the article i mentioned above https://scroll.in/article/1024624/caste-threads-are-spawning-deadly-conflicts-in-tamil-nadu-schools

Disclaimer: It is going to be a lengthy comment.

I am a big fan of ‘Panchayat’ series and having spent all my summer vacations as a child in small village while being in Mumbai for the rest of the year, I really get what series is trying to show here . I myself belong to an OBC caste and enjoy friendships with people belonging to various castes. I have had more good experience with Brahmins than bad. Maybe I am one of the few privileged ones.

Until I read this article I was not aware of Brahmin caste names of North India just like some of the other commentators here. So this article has given me something to think about.Below are just my few opinions.

1. We all know that whatever we see on TV has effect on subconscious mind. Marketing these days exploits this phenomenon thoroughly. So I do believe all Brahmin setup is not nothing or something to overlook. I wouldn’t like to watch a series only filled with characters named Joshi, Kulkarni, Chitale, khare etc.

2. Having said that, as Ajit Yadav mentioned in his comment, I have also seen villages is Maharashtra which are predominantly occupied by people belonging to a single caste or even single surname. So I can give benefit of doubt that the series is setup in a Brahmin Village.

3. One of the point where Pradhan Pati tells his wife about Sachivji ‘ अरे अपनिही बिरादरी का है भाई ‘ that holds true for any caste. In any caste, even today, a father would want his daughter to marry in the same as a first preference.

4. Pradhanji facing a challenge from another Brahmin in my opinion is pretty much okay, rather welcome. Had it been from someone from another caste then definitely that would have been something portraying divide on the basis of casteism. Rather in reality, in villages typically political fights are among the different castes. Each caste sticks to their representative exhibiting caste unity.

I consider media as a way to change or transform the society. Given the creativity of TVF I hope they read this article , mull over and try to touch the important problems our country and it’s villages are facing. All round representation of castes is also welcome . I really liked the firm stand taken by Pradhanji ( Neena Gupta ) in the ‘ बवासीर ‘ episode in the face of resistance. Would like to see something similar. Good luck !

This is actually mirroring the society than what the show failed to. Like pointed out, seems like only the upper caste ppl have enjoyed the show and willfully avoiding such conversations.

While the west is fighting for equal representation, including the giant Marvel franchises, pity Indian shows are still going ‘backwards’ and regressive in the name of humor!

I did notice the all brahmin characters of the show and it bothered me. But, at the same time the show wasn’t trying to be an activist one. And I didn’t feel for once that Abhishek was being glorified as a hero.

I also think that Siddharth wasn’t really from a privileged caste and Abhishek just made it up to prevent a catastrophe (which shouldn’t exist but he knows that it does exist).

Also, the instance of dance performer, clearly displayed that the idea behind show was not bigotry.

The show displays what society is, how people who know that it is too much flawed try to cope with it. I am a rebel myself but I know not everyone can be a rebel and definitely not everytime.

Writing an article demands you to speak up your mind, the daily lives of people, sadly don’t.

Panchayat series portrays life in a north indian village more or less accurately.

Villages are segregated along caste lines in North India , especially UP. In this case it happens to be a Brahmin village, had it been a Yadav or Thakur village, maximum characters would have been of those castes.

You have to understand this is not a series with a social justice message it potrays situation as it is. How can you expect it to show a brahmin, a yadav, a dalit negibhours in a village in UP when it is not true, let alone muslim.

Caste is a reality and movies with social messages are required but every movie cannot be expected to do same. Every movie cannot be Article 15 some will be Panchayat (series in this case) and that is OK.

What about the webseries like patallok and sacred games where Brahmin were shown as outright monsters or in the track of azeeb Dastan of Netflix where they actually showed a woman getting promotion because she belonged to Brahmin community against a woman from dalit community when it’s always the opposite . I never saw a single article then from anyone against these characterization s but instead a show which doesn’t even show a single aspect of any exploitation you jumped with your pseudo intellect..go to any village of UP n Bihar u will always find that in a village most people belong to the same community.. this article is quite shallow.. gain some knowledge of ground realities next time.

What a bad article written with a preconceived notion. It is such a nice show. But some people just want to find caste in everything. Indians have started beyond caste but some people can’t go beyond that. Caste should be made irrelevant not be made focal point of our society.

I noticed the UC tendencies of the show, but I brushed it off thinking the makers are mirroring the society as it is and showing the brutality as it is. But the end credits point was an eye opener, the whole cast is filled with UC surnames :O that’s incredibly weird and the makers should rethink their casting game.

I really enjoyed the show. The humor of it. The whole setup was quite humorous and joyful. But I didn’t think of this point of view even though as I took notice of the few caste based dialogue that appeared explicitly in few scenes. I think they are mocking the villages that are similar to that in the show and the hero by making a show like that.

The series is more of a reflection of rural India than projection of casteism. It’s sensible to watch it the way it is rather than through the shades of caste and oppression. It reflects many manacles ranging from dowry to blind faith system that have handicapped the society. It would help the general crowd if critics are not biased and do not disseminate skewed theories/propaganda.

Hi, wasn’t this the entire point of the show? To depict existing realities in Indian rural settings? Though I appreciate the analysis and noticed most of these aspects while watching the show, I believed they were present to convey the reality to those watching.

Well-written, incisive article – but should be briefer for internet readership. Prominent news websites keep the main article readably brief by including hyperlinks to more detailed elucidation of briefly mentioned but important items in the main article.

Your analysis shows how much you are disconnected from the reality of today’s socio economic reality. Panchayat official and bdo are state public servants who come from competitive exam where affermative action is provided to vulnerable group ( not debating here on the policy of reservation perse just stating a fact) and 1/3 rd reservation is constitutionally mandated at panchayat level too. So there is no question of representing any cast here it happens to be the case in many areas and also there are many cases where the whole village admin is not upper caste.

Secondly if panchayat sachiv was from vulnerable group and bdo was uc you would have made the argument that why panchayat sachiv was shown from vulnerable group and not bdo ( as it is a higher position in the hierarchy).

And lastly an eye opener for you,casteism today exist not only among uc but also among vulnerable sections. In places like up and bihar various obc and sc groups are much stronger politically and financially than uc.

Truly a eye opening article i also felt the same while watching the series! This show is based on the deep rooted casteism ideology, which we found in every place of the india specially the rural area. And if the creator of this series had showed the some courage to highlight the pain and anguish of the lower caste people via their show, then i would have might like it. But its keep continuing show the superiority of the upper people by asking each other surname again and again. And their good behaviour depend on your caste, i wonder what would have happened if the secretary were from the lower caste! I think that would be great plot for the entire show

Wow, great analysis. I haven’t seen second season yet but now I will. The points you have included may be not seen to many people cause they were just watching but as a writer you did great. We just can’t deny that 👍

thanks for the review…value it and can empathise with it. I have worked in villages and I know villages have caste clusters. group of people from a particular caste live together. each caste need another caste and in this sense the novel ‘raag darbari’ does flawless review of village life even if it is old. it is a worthy satire. I guess the series maker could have read it as the author of novel has surname shukl. but yes such kind of skewed representation in serials is worrisome. even a brahamin glorifies himself by offering food to the dom (one who plays role in cremation) on certain occasions. and the latter is happy with this mutual survival. rest of the castes too take pride in their work and caste ancestry. but yes oppression is not welcoming and prosperity of all should be our motto in society. and we must think that how may we get it.