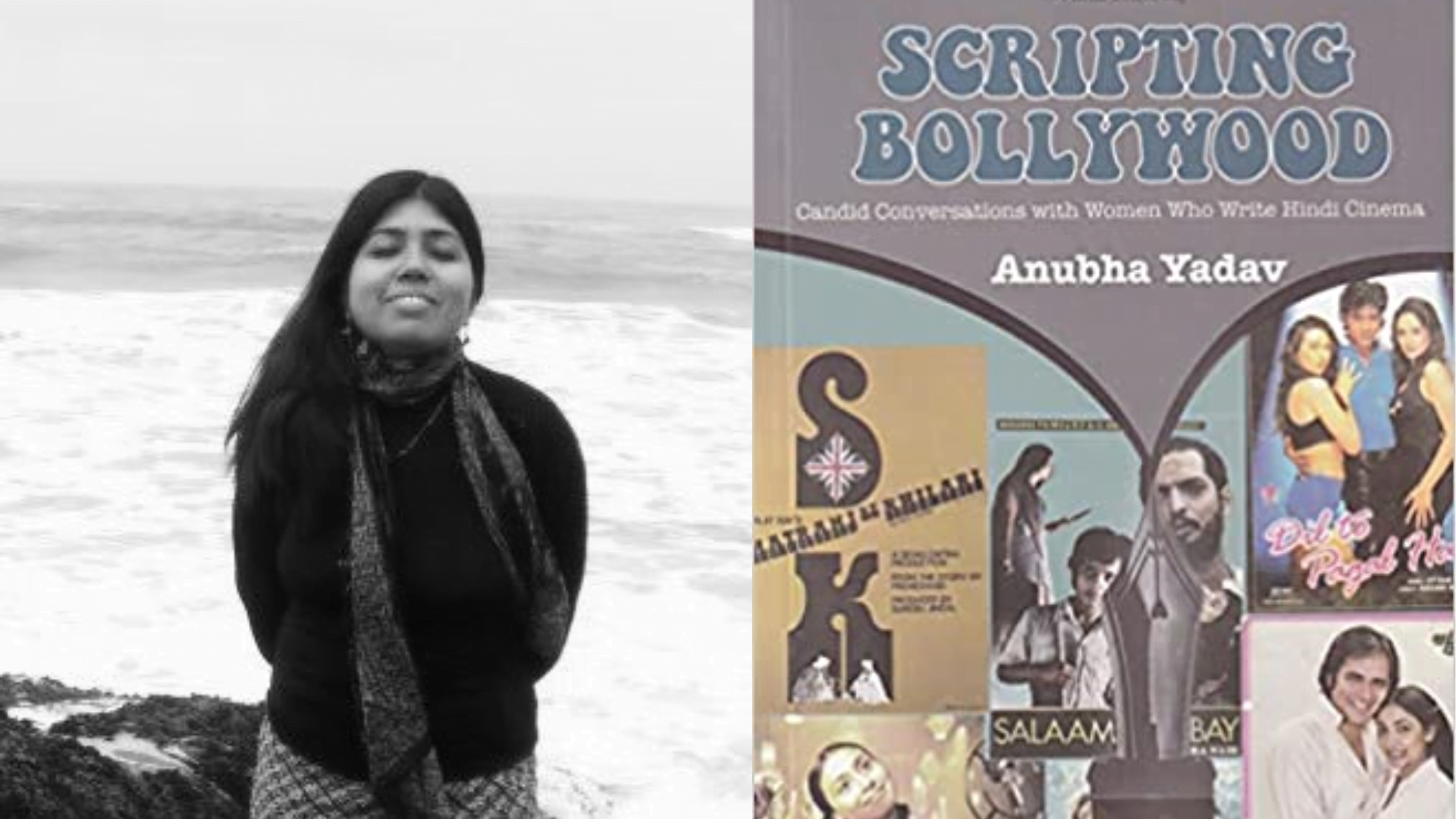

“Thinking women directors and screenwriters have a tough time in our industry”, states Kamna Chandra as she narrates the paucity of space Indian cinema has hitherto cultivated for movies on women’s issues in the book Scripting Bollywood written by Anubha Yadav. Extensively researched and intricately crafted, the book is a documentation of the imperative role played by women screenwriters and the even salient issue of their labour being underpaid, plagiarised, sidelined and never accepted, recognised or celebrated enough.

Documenting the role of women in cinema

At the initiation of the book itself, Yadav underlines how women have contributed to Indian cinema on a colossal scale and yet how their achievements have been relegated to the margins. Scripting Bollywood also underlines archives of women’s work disappearing from the public domain after being handed over to men. The patriarchal fabrication of history is what compelled Yadav to commence this book.

While historically, there has been a general invisibilisation of scriptwriters with the sole focus on actors, directors, singers, lyricists and choreographers, the work of women scriptwriters has been wilfully neglected further. Yadav ponders, laments and asserts how even stalwarts like Ismat Chughtai, Sai Paranjpye, Shama Zaidi have been denied and continue to be denied their place in history. However, Yadav doesn’t curb her curiosity or agitation there itself; she goes ahead and brings forward this paramount piece of history in her book.

While historically, there has been a general invisibilisation of scriptwriters with the sole focus on actors, directors, singers, lyricists and choreographers, the work of women scriptwriters has been wilfully neglected further. Yadav ponders, laments and asserts how even stalwarts like Ismat Chughtai, Sai Paranjpye, Shama Zaidi have been denied and continue to be denied their place in history. However, Yadav doesn’t curb her curiosity or agitation there itself; she goes ahead and brings forward this paramount piece of history in her book.

Scripting Bollywood begins in chronological order, putting together tiny but important remnants of history, pieces which have been scattered and thrown all over. In a linear, chronological order, from pre-independence to the end of the 20th century, Yadav enlightens us on women scriptwriters who often were the producers, directors, writers, music composers, actors and singers for their films. From early silent films to the talkies, early film women and their foundational role in Bombay cinema, their lives, their trials and tribulations, and their successes, Yadav narrates them all, and not for a moment does one feel helpless victimisation or a dehumanising deification of their journey. Yadav does not trivialise their trials, nor does she romanticise their success earned despite the same.

In the early chapters of the book, Yadav elucidates pioneering women in cinema and art, such as Fatma Begum, Jaddan Bai, Begum Para, Protima Dasgupta, and Ismat Chughtai. The interviews follow five decades of screenwriting in Hindi cinema, from the 1970s to date, and the yellowish tint of the pages only ameliorates the aura of the same. Though for someone who is not well-versed in the languages these screenwriters write in, it could have been possibly more enriching and engaging had the book contained pictures of the movies or women it talks about alongside the notes that it contains. It would have made the faces and facets of these women and their work more recognisable, given women scriptwriters are not extended their rightful representation by the cinema industry as well as the media.

Scripting Bollywood begins in chronological order, putting together tiny but important remnants of history, pieces which have been scattered and thrown all over. In a linear, chronological order, from pre-independence to the end of the 20th century, Yadav enlightens us on women scriptwriters who often were the producers, directors, writers, music composers, actors and singers for their films. From early silent films to the talkies, early film women and their foundational role in Bombay cinema, their lives, their trials and tribulations, and their successes, Yadav narrates them all, and not for a moment does one feel helpless victimisation or a dehumanising deification of their journey. Yadav does not trivialise their trials, nor does she romanticise their success earned despite the same.

From film financing to archiving to writer’s credit contract to censorship to political opinions, from copyrights to royalty and the and the lack of them, from fees to new genre practices to how screenwriting is now taught to mentoring young writers; of money earlier being pumped to the underworld, the women bear their hearts out. They also poke about how unionising has helped screenwriters the work the screenwriters association has been doing. The book brings to light the dismal reality that even now, women are not writing even 10 per cent of the films in Bollywood.

Chronicling cinema as the reflection of society and vice versa

Along with the detailed documentation of the work of these women, Scripting Bollywood both irrevocably and extensively manifests the changes that have taken place in society, the film industry, and art and how they influence the thematic and writing practices, as well as working conditions of women storytellers from mainstream parallel to the middle cinema to online platforms.

From the yesteryear star Ismat Chughtai who was a revolutionary dialogue writer, story writer, screenwriter, scriptwriter and who also worked on indoor sets, to a contemporary female scriptwriter who spoke about how a man on the set dismissed her opinion and stopped it from being implemented, extended an unwarranted touch and asked her out for further unwarranted touches, and how she could not react for fear of being labelled a “bitch”; the challenges faced by women are never-ending.

More importantly, the book also engages in conversations about women writing not only romance or family drama which have been stereotypically associated with them and boxed into, but also women who write science-fiction, action, war or neo-noir thrillers, who write about specific causes as well as universal emotions. She also documents the criticism that women scriptwriters have for each other for instance, Farah Khan has been criticised for creating “crass” content.

The book explores how different women experience, analyse and accept their identities and realities. The experiences of women screenwriters who have worked with collaborators have also articulated how such work situations get impacted by gender and also, at times, embolden the women when the male collaborator endeavours to create an equal space.

Patriarchy and gendered expectations

Most women scriptwriters have openly accepted that society functions on hypocritical standards for women, and even in these seemingly progressive spaces, women are expected to perform domestic duties, marry at a certain age and cater to the needs of their families and friends. It becomes more about women supporting each other and patriarchy still perceiving them as either voiceless entities or boxed creatures. Even as the women win esteemed awards and Yadav expresses, “I still remember the pride in the mother’s eyes as I interviewed her daughter.”, there is still a long way to go.

However, even as one celebrates the journey of these scriptwriters, one can’t help but ponder the amount of privilege that they come from. These are women who came from families that, even decades before independence, sent them to study in London and Germany and American boarding schools, women who had Ravi Shankar and Faiz Ahmad Faiz coming over for visits at home, whose fathers were in the Constituent Assembly and whose mothers were prominent artists themselves in fields including Hindustani theatre, which are related to Shyam Benegal and Guru Dutt who introduced them to literature and launched them in cinema, uncles who were directors and who introduced them to filmmaking, women who grew up in Australia because her grandfather was posted as India’s first high commissioner, and women who had Vasanthi Padukone as a grandmother and who introduced them to epics, who have had the privilege to read. They were wearing the same sari her mother wore when receiving Padma Bhushan.

Not only has the book recorded the history of women in cinema and the lived experiences of women currently working in cinema, but it has also delved into the thematic restriction imposed on women and the self and societal emancipation of women. The book does not put women on a pedestal, asking them to be perfect and vilify them if they aren’t, nor has the writing put the burden of morality on women who are themselves at the end of being demonised.

Sexism and gender violence in the movie sets

From the yesteryear star Ismat Chughtai who was a revolutionary dialogue writer, story writer, screenwriter, scriptwriter and who also worked on indoor sets, to a contemporary female scriptwriter who spoke about how a man on the set dismissed her opinion and stopped it from being implemented, extended an unwarranted touch and asked her out for further unwarranted touches, and how she could not react for fear of being labelled a “bitch”; the challenges faced by women are never-ending.

At the beginning of the book, Yadav asserts, “to not subsume all differences into one larger identity and recognise that their challenges are gendered as much as they are further defined by sexuality, class, caste and other criteria.” One needs to add region here for the experiences of women in Bihar, Jharkhand, or Nagaland are neither similar to each other nor similar to those of women from Delhi, Mumbai or Bengaluru, especially these women who grew up attending film festivals at these privileged locations. While the points made in the book are paramount and need to be acted upon, one cannot ignore the overall gender binary that these women scriptwriters speak in. While rightfully criticising cishet men for not being inclusive towards women, cishet women themselves also invisibilise the existence, intelligence and labour of trans women.

The women writers speak of how earlier there would barely be a couple of women on the set, and there were no separate loos, though now this has seen changes with time. They write about writing autobiographical accounts of sexual violence they have faced and changing the climax to find the right ending to their story, an ending which they did not receive in real life.

Given how women have been denied the bare minimum, in the book, the women scriptwriters express intense gratitude towards men who have done the bare minimum of crediting their work, listening to their voice or paying them on time. Given male entitlement, in a book documenting men and authored by a man, one does not find men being grateful for these basics.

Most of these women were born in privilege and their journeys reflect the same. However, Yadav is not to be blamed for it. She has only put a mirror on the past and the present, and if the reality that gets canvassed in the mirror is problematic, the fault does not lie with the mirror itself.

Gender binary and the invisibilisation of the spectrum

At the beginning of the book, Yadav asserts, “to not subsume all differences into one larger identity and recognise that their challenges are gendered as much as they are further defined by sexuality, class, caste and other criteria.” One needs to add region here for the experiences of women in Bihar, Jharkhand, or Nagaland are neither similar to each other nor similar to those of women from Delhi, Mumbai or Bengaluru, especially these women who grew up attending film festivals at these privileged locations. While the points made in the book are paramount and need to be acted upon, one cannot ignore the overall gender binary that these women scriptwriters speak in. While rightfully criticising cishet men for not being inclusive towards women, cishet women themselves also invisibilise the existence, intelligence and labour of trans women.

Women scriptwriters but coming from privileged and protected caste, class and regional locations

However, even as one celebrates the journey of these scriptwriters, one can’t help but ponder the amount of privilege that they come from. These are women who came from families that, even decades before independence, sent them to study in London and Germany and American boarding schools, women who had Ravi Shankar and Faiz Ahmad Faiz coming over for visits at home, whose fathers were in the Constituent Assembly and whose mothers were prominent artists themselves in fields including Hindustani theatre, which are related to Shyam Benegal and Guru Dutt who introduced them to literature and launched them in cinema, uncles who were directors and who introduced them to filmmaking, women who grew up in Australia because her grandfather was posted as India’s first high commissioner, and women who had Vasanthi Padukone as a grandmother and who introduced them to epics, who have had the privilege to read. They were wearing the same sari her mother wore when receiving Padma Bhushan.

From a distance, these women writers mention about gardeners, washermen and milkmen — largely professions performed by the marginalised from a distance. They also openly speak about growing up around “Kayasthas, Banias and Brahmins” and characterise their protagonist with regard to their Brahmin location.

Their privilege also extends them the relative confidence to take up space, and extends them relative protection from violence. It also gives them a space to trivialise their own gendered experiences. Though some of them also accept that when women receive power, they also go on “embodying everything that they have fought against. They take on the same power structures, the same way of looking at the world, the same way of gazing at a woman.”

A peek into screenwriting as an art

Scripting Bollywood also gives an idea about the art of screenwriting as the women each share their writing process, be it the infrastructure they use or the software they work on and how men are privileged to let go of any domestic duties and women are snatched of their creativity and imagination because of being overburdened.

Also read: 12 Powerful Books Written By Women Writers In 2020

Most of these women were born in privilege and their journeys reflect the same. However, Yadav is not to be blamed for it. She has only put a mirror on the past and the present, and if the reality that gets canvassed in the mirror is problematic, the fault does not lie with the mirror itself.

Also read: Differentiating Between Women-Centric Films And Feminist Films

Featured Image Source: Anubha Yadav On Twitter, Amazon

About the author(s)

Ankita Apurva was born with a pen and a sickle.