Even after the partition, the conversation around love jihad has frequently re-surfaced. In the early 2000s, politicians from both the Bhartiya Janata Party and the Indian National Congress expressed their concerns about the forced conversion of Hindu women by Muslim men. The transition of this political debate into full-fledged legislation was catalysed by the judiciary.

The jurisprudence around love jihad was crafted by the courts by virtue of various cases they encountered. In a few cases, couples approach the courts in pursuance of various pro-love strategies like seeking protection from illegal detention, seeking the issuance of the writ of habeas corpus and praying for the quashing of the First Information Report to protect themselves from the disgruntled parents.

The jurisprudence around love jihad was crafted by the courts by virtue of various cases they encountered. In a few cases, couples approach the courts in pursuance of various pro-love strategies like seeking protection from illegal detention, seeking the issuance of the writ of habeas corpus and praying for the quashing of the First Information Report to protect themselves from the disgruntled parents.

In another few cases, the parents of the women also approached the courts for the issuance of the writ of habeas corpus to get the custody of their daughter back. In another case, a Hindu woman approached the court for the annulment of her marriage as the conversion was induced by fraud, and she did not want to stay with her husband. In all these cases, the courts went into the bona fide of conversion of the woman, even when the issue was not agitated by the parties.

The common theme in these cases was the court’s concern for protecting the “seeming social fabric”, even if that came at the cost of the individual’s right to freedom of religion. The courts have opined in a plethora of cases that a conversion can be considered to be bona fide only if there is a change of heart and an honest conviction in the tenets of the new religion.

If a person converts to commit a fraud upon the law or with the object of creating a ground for some claim or right, such a conversion cannot be considered bona fide.

A typical case concerning interfaith couples, irrespective of whether it is filed by the couple for protection from the parents, by the husband for the production of his wife or by the parents for the production of their daughter, commences with an examination of the facts. However, this examination is clouded by practical challenges and gendered procedures.

The courts have held in cases ranging from Lily Thomas v Union of India to Priyanshi v State of UP that conversion solely for the sake of marriage is not valid.

Although the Supreme Court (‘SC’) upheld the individual’s right to marry the person of their own choice in Shafin Jahan v KM Ashokan (‘Hadiya case’), thereby over-ruling most of the precedence summarised above. Yet, a division bench of the SC recently passed oral directions asking the husband to submit an affidavit to prove the bona fide of the marriage.

Parents make wild allegations against the husband. They bring an action under kidnapping, abduction and rape against the man. They also make allegations of theft against their own daughter to be able to recover her from something they see as an undesirable marriage.

Further, the Allahabad HC (‘AHC’) passed a per-in curium order, post the Hadiya Judgement. The AHC held that conversion solely for the purposes of marriage was not bona fide.

Thereafter, a division bench of AHC overruled this per-in curium order. But these conflicting judgements of the courts point to a larger issue of uncertainty, as another HC can pass another per-in curium judgement on this issue, thereby muddling up the jurisprudence even further.

Amidst this hostile confrontation, the woman bears the onus of proving her capacity to consent because the mere age no longer remains enough to prove her competence. More often than not, she has to prove her rationality to a privileged male judge who carries gender biases of women being incapable of making reasoned decisions even after acquiring adulthood.

Challenges faced by litigants

A typical case concerning interfaith couples, irrespective of whether it is filed by the couple for protection from the parents, by the husband for the production of his wife or by the parents for the production of their daughter, commences with an examination of the facts. However, this examination is clouded by practical challenges and gendered procedures.

Parents make wild allegations against the husband. They bring an action under kidnapping, abduction and rape against the man. They also make allegations of theft against their own daughter to be able to recover her from something they see as an undesirable marriage.

Amidst this hostile confrontation, the woman bears the onus of proving her capacity to consent because the mere age no longer remains enough to prove her competence. More often than not, she has to prove her rationality to a privileged male judge who carries gender biases of women being incapable of making reasoned decisions even after acquiring adulthood.

The woman also bears the burden of proving that her consent was free, that she had not been raped, that she was not kidnapped or abducted, and that she embraced the religion on her own accord.

She fights such battles against her own family members, on whom she has been financially dependent. Thus, the cost of litigation is either taken up by her husband or her affinal family, which is a contesting party in these cases.

Judges can never examine facts in toto as their examination is clouded by their subconscious biases and the different realities of the litigants.

Further, constitutional courts entertain the cases concerning interfaith marriages under their writ jurisdiction. Article 32 empowers the SC to issue writs to protect the fundamental rights enshrined in part 3 of the Constitution and Article 226 empowers the HCs to issue writs to protect the fundamental rights or for any other purpose.

These broad provisions lack the propositional guidance regarding what exactly a judge ought to do. The indeterminacy of the text of the law leaves them with no option but to subscribe to their own notions of fairness and justice.

This was also seen in the Hadiya case. The Kerala HC annulled the marriage even when the limited issue in the case was whether the writ of habeas corpus was maintainable. The inquiry under such cases is limited to the question of whether there is illegal detention. But once an individual is produced before the court and they say that they had been with someone out of their own will, the job of the court ends there.

The Kerala HC overlooked the fact that Hadiya had been produced in the court, she was an adult, and she had affirmed that she had married out of a free will. In another case, the court ordered a 10-day-long mental examination of a couple after they had entered into an inter-caste marriage.

This shows that judges are driven by social forces, which include their background, prejudices and worldview while deciding cases.

These cases involve the question of religion. The Indian population has a high quotient of an illusion of singular identity. Under this illusion, individuals believe that their religion is the most important part of their identity, and it subsumes all other facets of their identity. Indian judges are not immune from this illusion. This is why the question of a Hindu woman being co-opted into Islam can be a very sensitive and volatile question for many judges.

The anxiety to control the agency and sexuality of women lies at the heart of the love jihad discourse and an implicit ban on interfaith marriages. Given that more than 75% of judges in the lower judiciary, 92% of judges in the HCs, and 97% of judges at the SC are male, the conscious and subconscious biases against women play at the mind of the judges while deciding cases.

All in all, the more deeply embedded a biased, the harder it gets to detach oneself from it. Ultimately, the statutes do not mean anything in and of themselves and are given meaning by the judges. Further, it is only with the meaning declared by the judges that these statutes are enforced on the subjects.

Also read: Why ‘Love Jihad’ Is An Attack On Women’s Rights

The foregoing discussion makes it amply clear that the questions around interfaith marriages are not legal but political.

Thus, plausible solutions in terms of building a more conducive society for interfaith marriages can include sensitisation of judges on issues of religion and gender justice so that they are more conscious of their biases, promoting the culture of interfaith unions through popular politics and embedding a constitutional culture of acceptance in citizens. This will enable them to make the politicians’ respect diversity.

Also read: Love Jihad Law: Making Hindu Women ‘Nirbhar’ In ‘Aatmanirbhar’ India

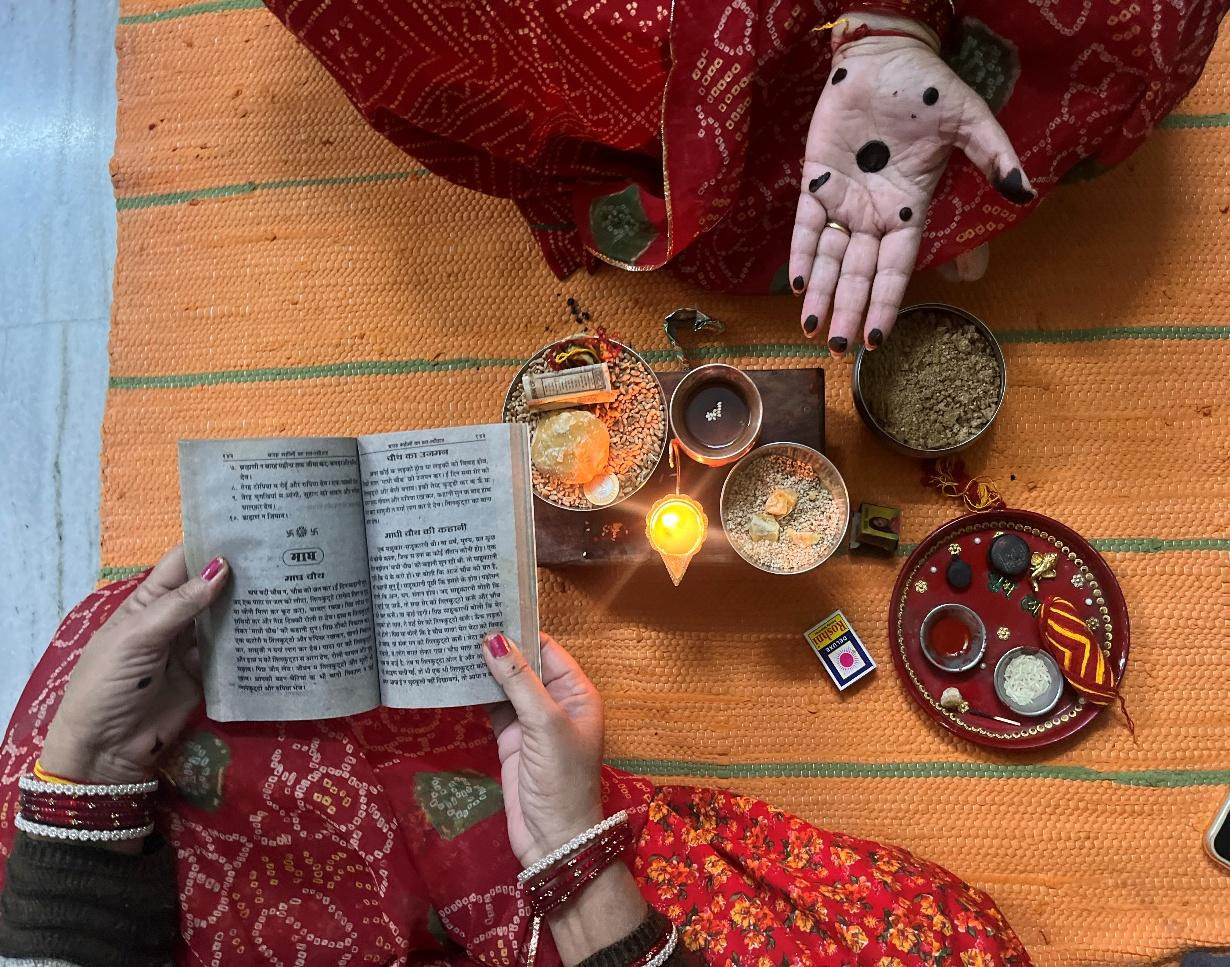

Featured image source: BBC

About the author(s)

Anchal is a second year student at national Law school of India University, Bangalore.

Big salute to love jihad survivors.

Govt should enact strong laws against love jihad. If strong laws exist, then there will not be cases like 1992 ajmer sharif dargah case