Dress codes are a set of guidelines for institutes and organisations that do not follow a common uniform for their students and employees respectively. In campuses, especially in universities and colleges, dress codes are an inevitable part of student life. They are particularly problematic in terms of gender bias, because most often, it is women and individuals from marginalised gender identities who are at the receiving end of accelerated dress policing.

Most often, the basis for maintaining a dress code in campus is to ensure ‘modesty’. This is nothing but a mechanism of controlling students and their bodies through surveillance, making them conscious about their physicality, as if they are nothing but objects. Inspecting them for discrepancies at campus gates, humiliating them in front of everyone for wearing something slightly different, body shaming, and the like, are all part of the process of ensuring dress codes.

This makes students insecure about their bodies and clothing, and fails to incorporate any ‘discipline’ or ‘modesty’ that the dress code claims to establish.

Most dress code rules are enforced due to the possible sexual harrassment or abuse that might take place in institutes because of ‘revealing clothes’. It has been fairly established that the reason for harassment is clearly not how the survivor dresses. To be passive in our reportage of such harassment (X was abused by Y) instead of actively putting the onus on the abuser (Y abused X) has only added to the problem.

Dress codes make a person feel objectified, and sexualised. To assume everyone has access to ‘appropriate clothes‘ that fit the dress code is also classist, which is aggravated when the institute’s administration treats the violators as second-class citizens, who also experience homophobic hostilities at times.

If an institution indeed feels that there must be some uniformity in clothing, then the resultant dress code must be substantiated with characteristics that are not founded on rape culture, body shaming, victim blaming or gender discrimination. An inclusive dress code must be gender neutral, applying to everyone. It should make space for gender expression, where non-binary and transgender students can express themselves without following the ‘gender specific norms’ imposed on them

Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity conducted a study where they found that girls of colour are more likely to be reprimanded by teachers for minor errors of wearing clothes that deviate from the dress code. This indicates that along with being subjected to policing regarding the dress code, multiple intersecting factors add to the humiliation and differential treatment faced by students of marginalised communities.

Moreover, people in an educational space come from diverse social, cultural and class backgrounds. Expecting everyone to have a wardrobe that is pertinent to the intstitue’s dress code is illogical, because everyone does not have equal access to resources. Imposing such restrictions may lead to unnecessary anxiety on the students, making them choose between their right to education and mere pairs of clothes, which may even cause them to drop out.

Additionally, demanding students to go back to home or refraining them from accessing the campus on account of dress code is an act of humiliation, and also physically exhausting, because students travel from far away most of the times to study at good institutions. It is also important to ask – Is clothing more important, or the right to education? Institutes with regressive dress codes assume the former.

Also read: Curfews, Dress Codes, Surveillance: Hostel Restrictions For Women Reflect Deep-Rooted Gender Bias

Ejin Jeong wrote in a 2015 blog post for SPARK MOVEMENT, “Each dress code rule must have an explanation, so much of the discontent with dress codes is that students often don’t understand why the rules are in place.” She says that dress codes “often feel arbitrary and unfair.”

If an institution indeed feels that there must be some uniformity in clothing, then the resultant dress code must be substantiated with characteristics that are not founded on rape culture, body shaming, victim blaming or gender discrimination. An inclusive dress code must be gender neutral, applying to everyone. It should make space for gender expression, where non-binary and transgender students can express themselves without following the ‘gender specific norms’ imposed on them.

Wearing what a person is comfortable in at a place of education, is a matter of right. Students must feel seen, heard and respected, and not be objectified or vilified for their choices of clothes. Intergenerational integration and mutual respect cannot be negotiated in campus spaces. In a democracy, freedom of choice is essential and inevitable, which institutes with regressive dress codes seem to have forgotten

Dress codes must take into account cultural practices like braiding the hair, having deadlocks, and the like. They should also be practical, with accurate reasoning behind their imposition. Ill-founded, patriarchal explanations like “Our culture demands it,” are impractical, sexist and arbitrary. Sending students home for not following the dress code is also impractical.

Dress codes should take into account geographic and weather conditions. They should not lead to objectification or sexualise the body. Victim blaming in the name of dress codes must also be interrogated. We must focus on the harasser and not the survivor. Humiliating the survivor will affect other survivors. Moreover, doing so is redundant as it will not stop harassment in any way. Policies should instead, be focused towards harassment and harassers.

Intersectional aspects must be considered while formulating dress codes. Some students have to make do with whatever they have, and to force them to wear what the institute wants is unacceptable, as they might have to spend the limited resources at their disposal to buy ‘acceptable’ clothing, which if they don’t, might lead them to not being allowed to attend classes (it’s possible getting into the college might have been difficult for them in the first place). Missing important lectures just because of a mere piece of clothing is unfair to students.

Instead of paying importance to dress, institutes should rather focus on bettering their educational policies, promote free will and thinking, focus on rationality, developmental policies, and student progress and safety in general. When we speak against the dress code, we are not here because we love protesting and ‘creating problems‘.

Wearing what a person is comfortable in at a place of education, is a matter of right. Students must feel seen, heard and respected, and not be objectified or vilified for their choices of clothes. Intergenerational integration and mutual respect cannot be negotiated in campus spaces. In a democracy, freedom of choice is essential and inevitable, which institutes with regressive dress codes seem to have forgotten.

Also read: Dress Codes: A “Code” For What? Misogyny And Gender Roles!

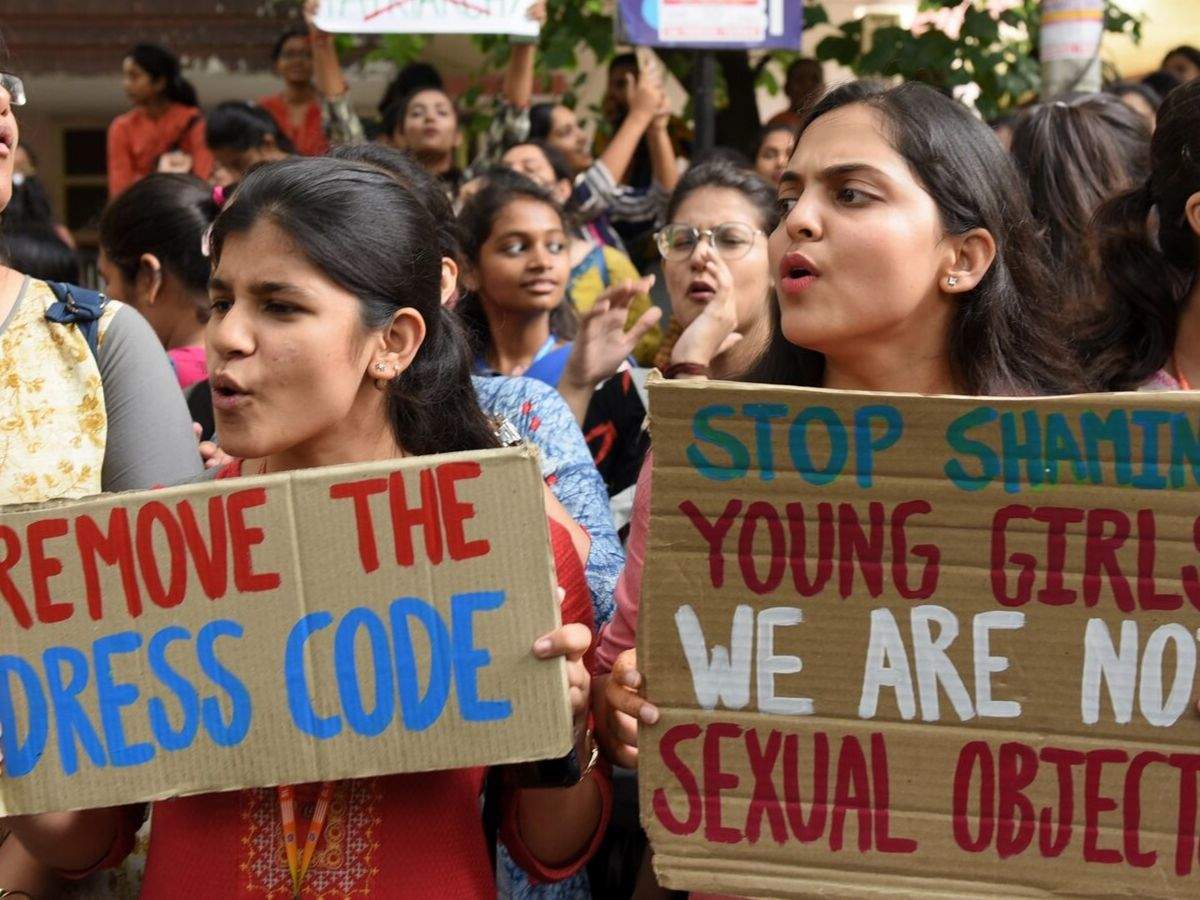

Featured Image Source: TFIPOST

About the author(s)

Meghna(she/her) is a humanities student from St. Xavier's College, Mumbai who is fond of everything sociology and psychology. She loves animals, reading and art

Every profession has a dress code. Office employees, police officers, doctors, lawyers, businessmen; all wear certain clothes to reveal who they are. Similarly, students should look like they are going to an educational institution, not a party. As for revealing clothes, the question that must be asked is why women’s clothes are shorter, tighter, transparent, etc. In the name of fashion, women are being sold miniskirts, short shorts, skimpy tops, tight pants, deep neck dresses – every effort made to show midriff, thighs, back, cleavage, etc. Men generally wear loose shirts and pants and do not reveal their body like women do, so a dress code for women is not sexism. It is equality.

We are supposed to dress according to the occasion and place. We dress differently to a job interview, beach, funeral, birthday party, and so on. Walk to a job interview in your pajama because it is your choice. Rest assured you won’t get the job. It is about being professionally dressed. In an educational institution you cannot indulge in skin show. You have to maintain decorum and civic sense. Besides, girls should ask themselves if they are comfortable wearing revealing attire while trying to emulate the women they see in movies, music videos, fashion magazines, etc. I have seen so many girls pulling and adjusting their short skirts and deep necklines, it is clear girls are not even comfortable wearing ‘what they want’.