Saadat Hasan Manto has been a stalwart figure in Urdu literature. Over the years, his stories have been widely translated into multiple languages and have been critically viewed by scholars and academicians. His stories attempt to expose the psyche of the macabre and deal with extreme situations and emotions.

Manto is famous for his partition stories and is acclaimed for representing the horrors of partitions truthfully in his stories. He is also one of the few writers who has dealt with the gendered aspect of partition and gives a perspective into the sufferings of women in partition through fiction. I will be looking at two of his stories, “a dutiful daughter” and “a bitter harvest”, in order to highlight how women as gendered subjects were a victim of different power relationships.

Manto is famous for his partition stories and is acclaimed for representing the horrors of partitions truthfully in his stories. He is also one of the few writers who has dealt with the gendered aspect of partition and gives a perspective into the sufferings of women in partition through fiction.

In “the dutiful daughter”, he writes, “The year 1948 had begun. Hundreds of volunteers had been assigned the task of recovering abducted women and children and restoring them to their families.”

Manto’s story, “the dutiful daughter” deals with the aftermath of Partition and the difficulties faced by the newly formed nations regarding women. Independence and Partition coincided for India and Pakistan, which led to a strange event in history which was both celebrated and mourned.

Indians and Pakistanis were overwhelmed with the two contradictory paths that this momentous event in history was following. In the aftermath of the duality of this event, a huge project was taken by the two nations, which was restoring the population of women who were abducted and raped, and was to be brought back to their own country.

How did they decide which country of belonging to abducted and raped women? What were the grounds on which it was decided? Was it religious, patriarchal, or State driven?

Looking into these stories, one might also criticise Manto for objectifying women’s bodies and for writing his characters in such a way which justifies their crimes owing to their madness or traumatisation. His stories overshadow the individual subjectivities of the perpetrators and create a causal relationship between the perpetrator and the crime committed.

Manto writes, “One heard strange stories. One liaison officer told me that in Saharanpur, two abducted Muslim girls had refused to return to their parents, who were in Pakistan. Then there was this Muslim girl in Jullandar who was given a touching farewell by the abductor’s family as if it was a daughter-in-law leaving on a long journey. Some girls had committed suicide on the way, afraid of facing their parents. Some had lost their mental balance as a result of their traumatic experiences.”

These incidents complicate the relationship between the victim and the perpetrator and dissociate the connection between the two. The relationship of hatred and dominance between the victim and the perpetrator gains several other nuances, and the female subject’s position gets embedded in multiple power relationships of the family as well as the State.

The refusal to return can either be a fear that her family will not accept her anymore, or it could be the result of the new relationships that she has formed along the way. The roles of a daughter, a wife, and a mother, lose their conventional meanings and are instead imposed by the family to return even without their consent.

Along with this, the State’s anxiety in restoring women was seen as a question of honour by the popular imagination of the country. Manto writes, “Sometimes it seemed to me that the entire operation was being conducted like import-export trade.”

Even though it was a relief operation and many women were grateful to return back to their homes, the grounds of the operations were driven by principles of the popular imagination of preserving the honour of women and treating them as the rightful property of the nation.

There was a complete absence of any further assistance to women in forms of therapy or to express their mourning, given that the Partition was hugely driven by gender dynamics and women’s bodies were treated as sites for revenge. Nobody was as marked and as vulnerable as a woman. Reflecting upon this, Manto says in the story, “When I thought about these abducted girls, I only saw their protruding bellies. What was going to happen to them, and what did they contain? Who would claim the end result? Pakistan or India?”

Manto further writes, “And who would pay the women the wages for carrying those children in their wombs for nine months? Pakistan or India? Or would it all be put down in God’s great ledger, that is, if there were any pages left?”

In the story “a bitter harvest”, we get a microscopic insight into the rape of women during Partition and how their bodies became bearers of religious identity. Qasim is traumatised by seeing the dead body of his daughter, Sharifan, who had been raped and killed. “On the floor was the nearly naked body of a young girl, her small, upturned breasts pointing at the ceiling as she lay on her back. He wanted to scream but couldn’t. He turned his face away and said in a soft, grief-stricken voice, ‘Sharifan’”.

Witnessing this, Qasim is filled with rage and wants to take revenge. For this, he sets out to rape another girl whose body he can use to carry out his revenge. This cycle of revenge governs many rape narratives of the partition, where women were mutilated and raped because they were bearers of dual identities of religion as well as gender.

In the absence of any other outlet for mourning and the inability to process such extreme situations, Qasim follows the logic of revenge, which everyone around him follows. The image of Sharifan comes back to him again and again, thereby creating in him an unquenchable thirst to avenge her end. Manto describes him as, “a man demented” with “blood surging through his body, like boiling over which cold water is being sprinkled.”

Later, when Qasim reaches a house where he can see a young girl, he first asks her who she is, to which she replies, “I am a Hindu”. This incident foreground clearly the two identity markers necessary in order to carry out the cycle of revenge successfully. First is the identification of a female body, and the other is the religious identity. In this moment of interaction, the young girl is the representation of her religion in a gendered body.

Looking into these stories, one might also criticise Manto for objectifying women’s bodies and for writing his characters in such a way which justifies their crimes owing to their madness or traumatisation. His stories overshadow the individual subjectivities of the perpetrators and create a causal relationship between the perpetrator and the crime committed.

Also read: Manto Review: A Man Whose Story Is More Relevant Than Ever Today

Using the tool of macabre and dark representation, Manto is able to escape certain ethical responsibilities in relation to his writing. But the fact remains that his stories around Partition initiate dialogues and discussions on certain nuances of partition, which are overshadowed by the grand narratives of the State.

Also read: Saadat Hasan Manto And His ‘Scandalous’ Women

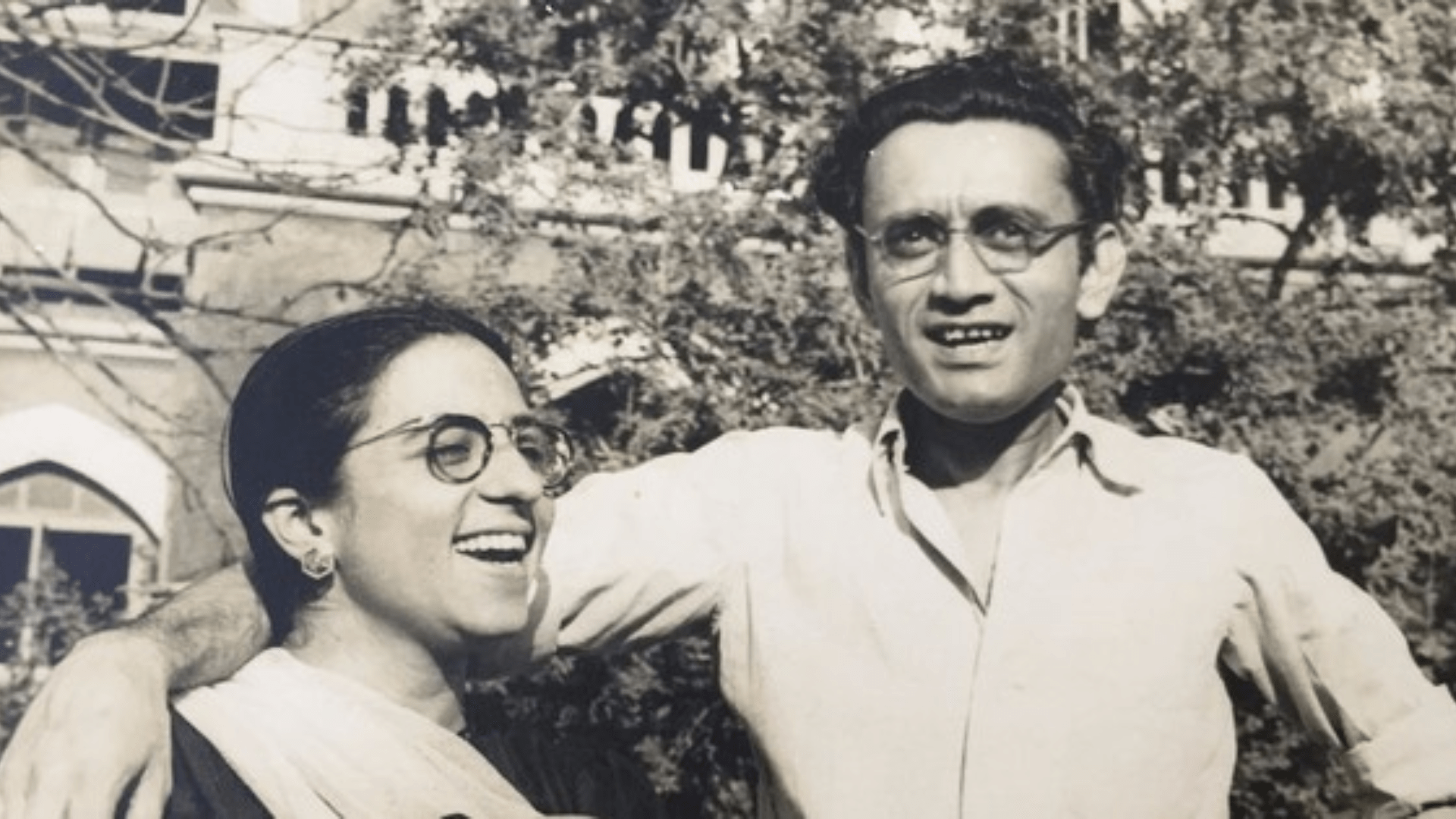

Featured image source: Scroll