When I was in school and environmental studies came barging into our curriculum, I remember the only outcome of its grand entry being a bundle of chart papers glittering on the school notice boards. I remember laughing at the irony with my friend, as school children do when they get ahead of themselves while complaining about the paper wastage that went into ‘saving the environment.’

But as I was passing through the green-glittered hallways, several years down the line, I realise now what I had then overlooked. As those chart papers dance around in my memories, I recall a picture of the planet with large doe-eyes and eyelashes. In other illustrations, those eyes would cry big tears, followed by a “save mother earth” slogan.

It is fair to say that a majority of us never question how ‘earth’ became ‘mother earth’, even though you need both soil and the seed to fully hop on the reproduction metaphor train.

One might argue that it comes from myths. In India, for example, in many Kali traditions, the story goes that tandav is performed as an act of wrath against the sins committed by man on earth. In that sense, many people read Kali as the angry avatar of nature.

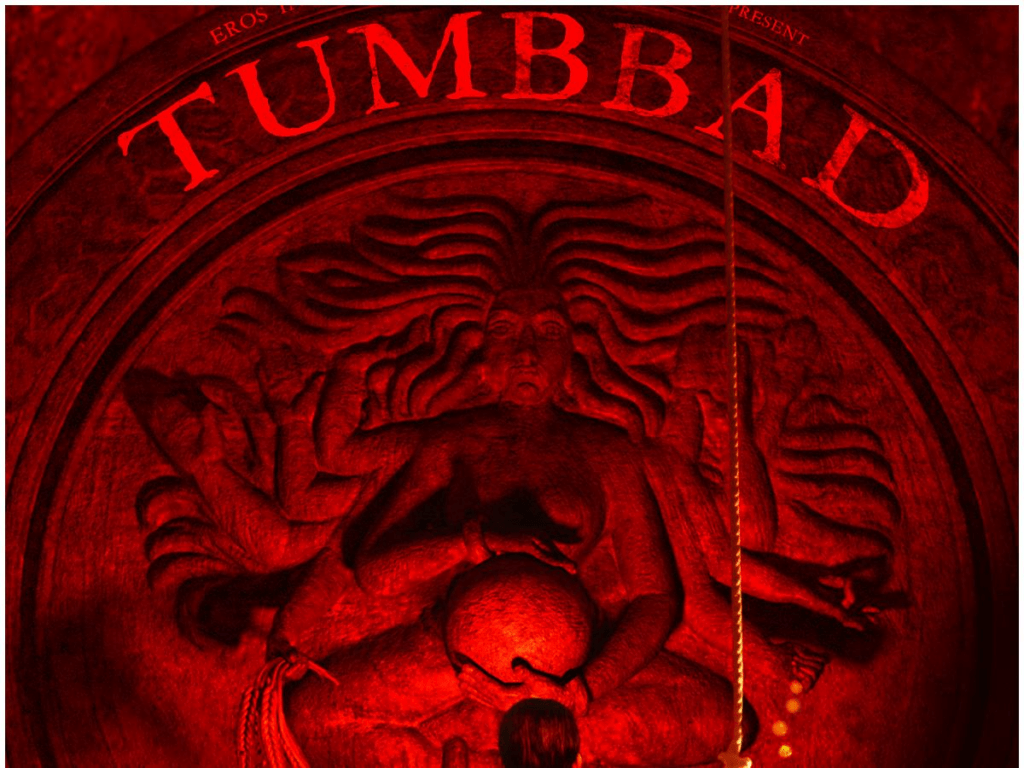

One of my favorite horror films, Tumbbad, also picks up on the same metaphor. This film ties myth with realism to extend the dark reality of environmental exploitation. In this story, we hear the myth of the ‘goddess of prosperity’ whose womb is said to be the earth.

Again, it is not just ‘woman’ and ‘nature’, it is mother nature. Hilary Klein argues that both feminist and masculinist discourses assume an intimate connection between ‘woman’, ‘nature’, and ‘mother’ to create distorted essentialisms around the nature of the female subject. She further argues: “The claim that women’s experience of nurturing labour is a process that is “closer to nature,” (…) further serves to root the category of ‘woman’ into the category of ‘nature’.”

Following the same metaphor, she grants wealth and food to her children and makes life possible. But as the story develops, her son Hastar becomes corrupted with greed and attempts to steal all his mother’s gifts for himself.

As a punishment, he is reduced to a demonic and monster-like existence. Cut to 1918, we see the story of a family’s quest to acquire Hastar’s treasure, a pursuit that does not end well. Regardless, the elder son Vinayak decides to pursue the treasure despite his mother’s warnings and in the end, manages to find it.

Growing rich by the day from Hastar’s treasure, depravity enters his life. I won’t spoil the ending for you, but the bottom line is that there are disastrous consequences of stealing from mother earth, in this case, literally from the goddess’s womb—a metaphor that directly indicates mining.

Also read: ‘Mother Earth’— Is Nature Gendered To Make Men Feel Superior?

In various kinds of literature, land is represented as a woman, often raped, looted, and parted from her rich resources. The tale then serves as a cautionary tale for man. Even Disney’s beloved Moana, loosely based on Polynesian mythology, is all about a male demigod stealing the heart of the goddess Te Fiti and in turn, leaving her in a fit of rage.

When enraged, nature turns into a mother, chasing after the child to deliver punishment. No wonder, even with the recent pandemic, ‘nature’s punishment’ was part of the conversation.

But this correlation is not just found in mythology. One of my favorite feminist scholars, Hilary Klein notes that even Marx creates “a masculine subject” who ‘labours’ to carve nature in his own form. Nature, which was originally feminine for this subject, is then converted into a mirror. In other words, he would create a mirror out of nature—a mirror that would represent male desire.

Several warnings already exist in the world, particularly related to religion, as to what happens when fantasy becomes a total reality. Probably, the construct of nature as a woman also started as a mere fantasy. But given the current situation of the environment, we need more action than fantasies to battle environmental change

Complex in theory, but as an image—a woman staring into a mirror, gazing at herself as if under the gaze of her male admirers produces a haunting visual. My concern here, although not original, is about the everlasting impulse of theory, tradition, and popular culture, as they re-endorse the hierarchical dichotomy of ‘man and woman’ as ‘man vs nature’.

Again, it is not just ‘woman’ and ‘nature’, it is mother nature. Hilary Klein argues that both feminist and masculinist discourses assume an intimate connection between ‘woman’, ‘nature’, and ‘mother’ to create distorted essentialisms around the nature of the female subject. She further argues: “The claim that women’s experience of nurturing labour is a process that is “closer to nature,” (…) further serves to root the category of ‘woman’ into the category of ‘nature’.”

It is important to dissolve such essentialisms. As environmentalists, we may fall into the trap of caregivers and forever be contained in the box of ‘mother nature’. But one might ask, what about those who feel divinely connected to the cosmic and feminine force of nature?—to put it in internet millennial language.

I often feel that romanticising nature is the same as romanticising anything else in life. You need to have the ability to distinguish between reality and fiction. Gustave Flaubert’s Madame Bovary is a fun analogy. It is a story about Emma Bovary who loves reading romance novels with glorious male heroes. But regardless of her fantasies, male characters in her life are highly disappointing. In the end, she is unable to deal with the difference between reality and fiction and gives up her life.

Here, let me kill two birds with one arrow (although in the interest of an essay on the environment, you may replace birds with apples). If you are a fan of cheesy romance fiction and if you’ve always questioned whether it problematises your feminism, the answer should be based on the same criteria—whether you define your fantasy as your reality.

Several warnings already exist in the world, particularly related to religion, as to what happens when fantasy becomes a total reality. Probably, the construct of nature as a woman also started as a mere fantasy. But given the current situation of the environment, we need more action than fantasies to battle environmental change.

Also read: Is Nature Queer? — Challenging Normative Ideas Around Ecology

References:

Marxism, Psychoanalysis and Mother Nature by Hilary Klein in Feminist Studies Vol. 15, No. 2, The Problematics of Heterosexuality (Summer, 1989)

Priyanka Kapoor is a postgraduate in English Literature from Lady Shri Ram College, Delhi University. She has been published on platforms such as The Indian Quarterly, Hakara, Voice and Verse Poetry Magazine, The Alipore Post, Phantom Kangaroo, and others. She was also shortlisted for R.L. Poetry Award and The Brooklyn Poets’ Fellowship for her poetry. Recently, her poetry got featured in the Yearbook of Indian Poetry in English (2020-21) (edited by Sukrita Paul and Vinita Agrawal)

Such an interesting essay, thanks so much for sharing!

The subject makes me wonder about this historical phenomenon of men being disjointed egos pursuing extremely abstract and individualistic ends amongst the backdrop of nature (which includes women and children). Women, LGTBQIA+, BIPOC, and children are to be used like natural resources. A man dying of thirst happens upon a natural spring that he drinks from to save his life only he is actually an uninspired writer and his “natural spring” is some person from the above mentioned categories who tells him their story which he then copies and publishes and continues his successful career. Sigh.

The reduction of “nature” and “woman” to “mother nature” seems to solve two issues for men: one, that nature must an “other” for man to be an individual. Because he cannot be an individual and live with or amongst nature and be guided, influenced, or subjected to natural forces. And two, that women must be mysterious and powerful and therefore potential threats to man’s assertion of his individuality. This second one solves the problem of being connected to or guided by genealogy and natality. If women are enemies, then man does not have to abide by society when pursuing individualism.

In modern contexts, such as the fantasies of anti-feminists, this story serves to make man the righteous victim of a world dominated by tyrannical, totalitarian feminists. Their domination is essentially their creation of the world (nature) in their image, their totalitarianism is equivalent to natural forces, and man’s victimization is the lack of individuality he possesses in the face of hostile natural/feminist forces that work explicitly against him. This is why he must imagine feminists as angry, hateful and spiteful. If they do not explicitly intend to obstruct man’s pursuit of individuality, they cannot fit into man’s view of a nature that is inherently hostile to his individuality and his world-shaping goals.