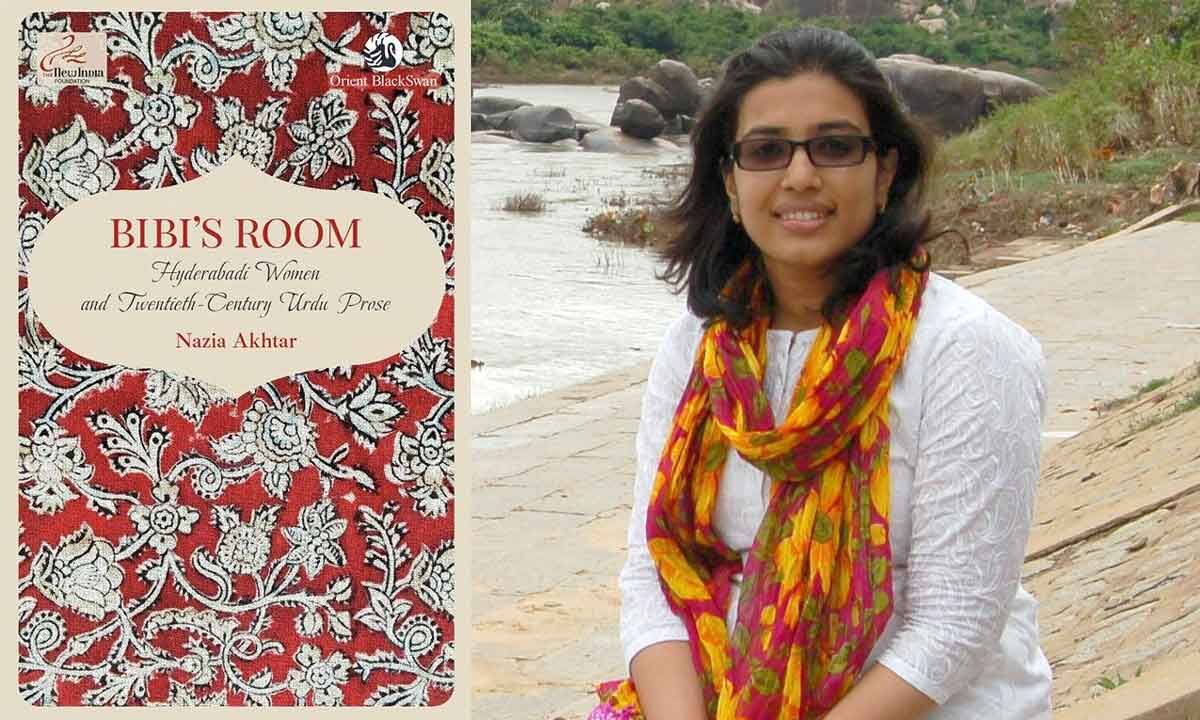

Nazia Akhtar, during her doctoral research on the Hyderabadi experience of transfer of power, realised how insignificant the legacy of Hyderabadi female Urdu writers is in popular consciousness. The only women Urdu writers that were read widely were from North India, such as Rashid Jahan, Ismat Chugtai, and Qurratulain Hyder. Very little is known and is available to the general public about the Hyderabadi women writers who were writing in Urdu because their oeuvre of literature had never been translated into English.

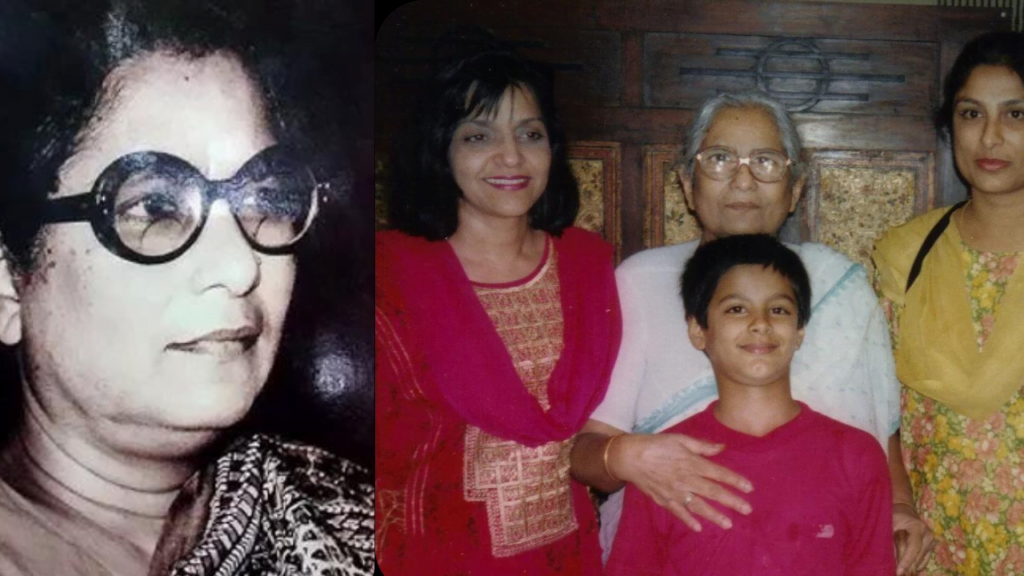

Through Nazia Akhtar’s Bibi’s Room: Hyderabadi Women and Twentieth Century Urdu Prose, an attempt has been made to remedy the systematic ignorance that prevails over South Asian scholarship when it comes to Twentieth Century Urdu Prose written by women. Bibi’s Room focuses on three women writers writing in Urdu at the socio-political backdrop of twentieth-century Hyderabad: Zeenath Sajida, Najma Nikhat, and Jeelani Bano.

The book is divided into three sections with each section focusing on the works of each of these writers and their general oeuvre of writing.

Zeenath Sajida’s ‘If Allah Miyan Were A Woman’

It is an introspective prose narrative written in the first person where the narrator, in the throes of menstrual cramps, wonders if it is a sin to be a woman. As she describes her hands and feet going numb with excruciating pain, she thinks to herself if Allah was a woman, surely She would not subject fellow women of the world to such strange aches and weaknesses of the world.

Then she uses the garb of pain-induced hallucination to assert a blasphemous claim that Allah Mian must be a woman. Throughout the prose, she uses proto-feminist arguments to justify her claim. If the Divine Being is love manifested, then who can better embody them better than a woman?

She writes, “As far as Allah is concerned, Akbar Allahabadi has this to say: ‘One who is easily understood, how can such a being be God?’ It appears that a disposition that cannot be easily understood belongs either to God’s person or to that of woman.”

She also boldly states that it is a transgression on the part of men to associate masculine gender with God’s Being. God has no gender but if humans were modelled after the image of God, God must be a woman.

She also uses unconditional love associated with motherhood with the love of God. A father needs social sanction to accept a child as his own. He can easily disregard a child born to a courtesan, servant, or in any other circumstances of wedlock. However, a mother’s love, much like God’s, is all-encompassing and never falters.

Sajida does not subvert the existing gender stereotypes but uses them to strengthen her argument and subsequently raise women’s position in society to a higher status than that of men. Very cleverly she seeks security through her prose by claiming that she too is a creation of God, and God is responsible for all thoughts that occur to her.

Other than ‘Allah Miyan Were A Man’, Sajida has also written several other essays such as ‘As We Do Exist, So Do Obstacles In Our Path’, ‘If I Were A Man’, ‘In Vain Do I Adorn Myself, For My Lover Is Blind’ where she uses deft humour and reasoning to talk about women’s experience behind closed doors and how they negotiate with patriarchy to carve out their existence.

In her essays like ‘Building a House’, ‘My Hens’, and ‘From Junkyard to Museum’, she satirises human nature and the inherent folly that resides within it. Through her essays and short stories, she also addresses themes of artistic journey, imprints of places and culture in an artist’s work, young love, courtships, desires, longing, and separation.

Sajida was a prolific writer whose name could be mentioned alongside Ismat Chugtai and Amrita Pritam. Through Akhtar’s translation, we are given detailed biographical descriptions, socio-political and cultural understanding of Sajida’s work and the impact she left on Urdu literature at large.

Najma Nikhat’s The Last Haveli

Besides having a tumultuous marital life, and being a hands-on mother throughout her life, Najma Nikhat has managed to write twenty-six texts in her lifetime. She thoroughly researched the subjects of her stories and writings. Akhtar explains why she chose this story to focus on: “My first reason is personal, in other words, affective and aesthetic: this is quite simply, one of the most beautiful stories that Najma Nikhat ever wrote. It represents some of the most characteristic formal qualities and thematic concerns of her oeuvre.”

Nikhat eloquently highlights the decaying state of the nawab and the poignant realisation that dawns upon the inhabitants of the haveli. She manages to evoke a melancholic response from the readers to the loss of the haveli to the emerging merchant class of the country without romanticising the exploitations of the nawabs and their feudal systems. Nikhat’s writing is timeless in its essence, focusing on the anxiety, grief, and helplessness of the women in the zenana as they watch the jagirdari coming to an end. Nikhat is also unapologetic in her candid portrayal of the exploitative nature of the socio-economic system of the older ways of life and how it entraps the very women who have been working under the jagirdari and sustaining it.

Nikhat’s writing marvels at us with its rich details and atmospheric verses. She refrains from making direct social commentaries but her stories end in a poignant poetic justice that makes us yearn for more.

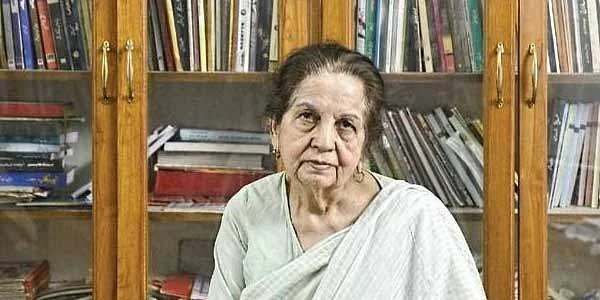

Jeelani Bano’s ‘God and I’

Jeelani Bano’s story God and I have escaped the notice of literary scholars and critics alike. It is riddled with philosophical contemplation and radical existential questions that plague the narrator as he struggles in his destitute circumstances.

Bano has written numerous short stories and essays. Her philosophical worldview and her oeuvre of writings have managed to evade any specific political alignment. However, her stories contain strong elements of progressive thoughts. Even though Bano had not received a formal education, her father, Hairat had immense influence over her life which was heavily reflected in her works. Bano’s diverse oeuvre of works deals with modernist techniques and themes, progressive concerns, and literary aestheticism. She deals with humour, social inequalities, class struggles, and communal discord.

Nazia Akhtar’s translation and discussion of these women’s works are an attempt to redirect scholarship towards the vast oeuvre of Hyderabadi women’s writing in Urdu.

The title of the book ‘Bibi’s Room’ refers to an essay by Zeenath Sajida where. It is an ode to Virginia Woolfe’s A Room Of One’s Own where she points out that a woman’s personal space, no matter who she is or at what stage of life she is at, is always expendable. Women writing is an attempt to carve out a piece of their personhood from nothing, from a space that is always denied to them by society. Akhtar’s Bibi’s Room is, in many ways, a gateway to the socio-political landscape of twentieth-century Hyderabad which allows us to take a look into women’s lives emerging from under the shadow of patriarchy.

About the author(s)

Debabratee (she/they) is a student of English Literature at Jadavpur University. When they are not found reading or writing, they are found running after their pet dog and cuddling with him. They are avid binge-watcher of all kinds of OTT content and like to dissect and analyse them in their free time.