Trigger Warning: Mentions of assault, violence

Recently, a family in Jharkhand faced extreme brutality over allegations of practicing witchcraft, wherein the villagers in Aswari launched attacks on them. They were brutally assaulted and force-fed human excreta. The family was accused of witchcraft after a child in the village took ill. The police have filed an FIR and arrested six persons.

A report by Scroll narrates the incident by the survivors. The woman spoke to the media stating that the family was first abused on 24th September 2022. “However, they came to my home again on September 25 at 11 pm,” the complainant said. “This time, they beat up two of my relatives along with my husband and me. We were made to eat human excreta and our bodies were burnt with hot iron rods.”

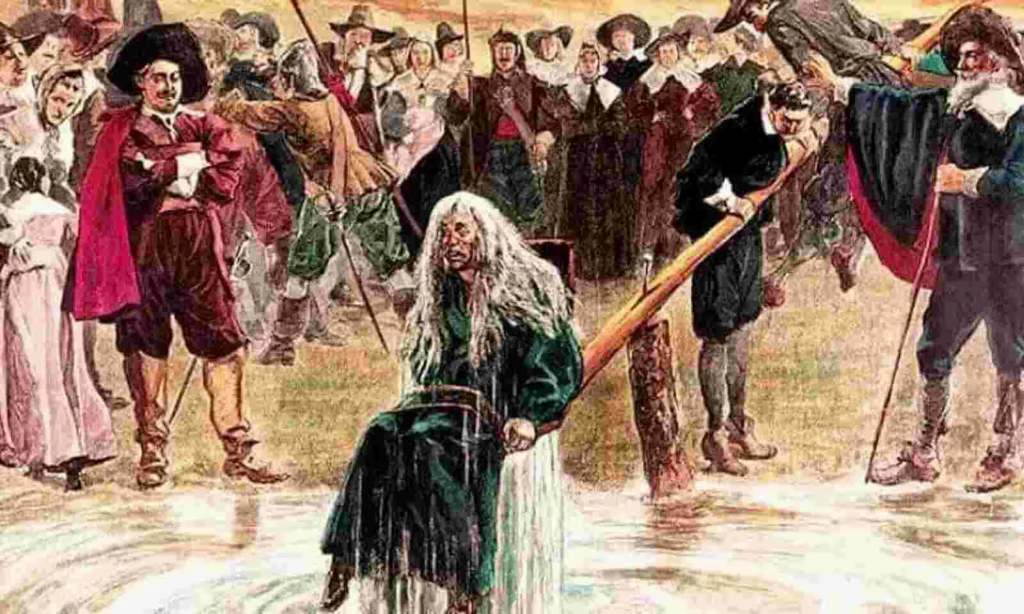

Gendered history of witch hunting

There is a gendered burden that women encounter when facing accusations of practicing witchcraft. Women have been historically disciplined through social norms and elaborate rituals following the accusation of practicing witchcraft.

These disciplining tools were extremely violent and have resulted in mass burning rituals. This gendered burden was witnessed in Jharkhand also as the family accused was predominantly a female household. Out of the four people brutally beaten, three were women.

The legal response in independent India toward witch-hunting has been beyond disappointing. At present, there is no central law in the country to tackle this. Due to the lack of uniformity and central push for stringent responses, State laws are not as strict as would ideally be preferred. At present, only eight states have laws for witch hunting, namely Rajasthan, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Odisha, Assam, Maharashtra, and Karnataka

The incident attests to how witchcraft is an accusation hurled at women globally throughout history. Witch hunting has been practiced all over history from Europe to the early modern history of Nepal. In India, the colonial period saw the most cases of witch hunting reported all over the country, and recent studies show that these accusations were disproportionately hurled at non-dominant and oppressed caste communities of a given region. There were mass and violent rituals to discipline these women.

Particular brutalities were reported from the Chhota Nagpur region in Madhya Pradesh. The Prevention of Witchcraft Act in 1735 Britain did not transfer results in India, especially because law and order was still a social function and social norms prevailed. A law set in Britain had no percolation in Indian villages and our social practices.

Legal response

The legal response in independent India toward witch-hunting has been beyond disappointing. At present, there is no central law in the country to tackle this. Due to the lack of uniformity and central push for stringent responses, State laws are not as strict as would ideally be preferred.

At present, only eight states have laws for witch hunting, namely Rajasthan, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Odisha, Assam, Maharashtra, and Karnataka.

Also read: The Gendered Accusation Of Witchcraft: Why Only Women?

Witch hunting prevails as a social practice that disciplines women through social norms. Historically, witch hunting’s prevalence has not been restricted to India. These practices globally have been used to target independent women who would be outliers in the prevalent social institutions

Most states in India do not have laws specific to witch hunting due to religious opposition. While Articles 14, 15, and 21 are constitutional guarantees that are violated, an absence of coherent, homogeneous laws is due to diverse causes. First, the instances of witch-hunting are geographically dispersed, and second, because of the disproportionate impact on women.

Though the history of this violence is not as historic as one would want to believe, as recent in 2014 in Gujarat, three women were attacked, and the villagers believed that the women through witchcraft were the cause of the death of two men in the village.

The Indian National Crime Bureau reports that between 2000 and 2016 alone 2500 Indians have been attacked due to such hunts. On the other hand, reports show that 83 percent of cases of witch-hunting from Orissa are restricted to six districts in the state.

Witch hunting in literature and popular culture

Witch hunting prevails as a social practice that disciplines women through social norms. Historically, witch hunting’s prevalence has not been restricted to India. These practices globally have been used to target independent women who would be outliers in the prevalent social institutions.

Nadia Hashimi speaks to so many varied ails in Afghan society, and the book “A House Without Windows” dwells on social norms and attributes practices of witchcraft to women. The book interestingly shows that women have reclaimed the title of being a “witch” to reinforce a safe life outlying the social institutions, like the protagonist in the novel kills her abuser husband in an act of self-defense. Local laws in Afghanistan do not account for self-defense as a reason for harming one’s husband.

Through her lawyer and her mother, she employs the defence of witchcraft and escapes prison by availing the punishment of social norms over death penalty. The movie Bulbul also runs on a similar narrative, where witchcraft and social norms are reclaimed for agency. Though the abject conditions and prevailing violence needs to be responded to.

Also read: Witch Hunting Trials: A Gendered Practice Of Punishment That Continues Even Today

Violent disciplining of human beings for violation of social norms threatens the very core of humanity. The legal response to the practice of witch-hunting can no longer be diverse and non-coherent. The patriarchal and casteist overtones of the crime make it essential to see witch huntings amongst the largest rubric of caste and gender crimes.

The state cannot choose to turn a blind eye to the cost of the crime and the coherent response it needs by bringing to evidence the idea that witch-hunting is a geographically isolated event. Neither is witch hunting practice of the past nor is it a misguided crime. It is time we recognise that witch hunting is systematic and is a key tool to regulate individuals, especially women who question social norms.

About the author(s)

Assistant Editor FII, MPhil scholar from the Centre for Political Studies in Jawaharlal Nehru University, working on the intersection of feminism, law, and the Indian state.