Slightly ahead of the much-awaited Netflix original Blonde, the film is generating ripples on the controversial life of Norma Jean Baker, known as Marilyn Monroe. In the quest to desexualise Monroe, the film serves precisely the opposite.

Rampant in the 1950s, an actress’s human identity was often shaped by the public nature of the profession and the display of body it entailed for women. Monroe’s case has become one of the quintessential examples in popular media in showcasing the sexualisation of an actress’s identity and the resultant exploitation, evoking a narrative of victimhood.

Andrew Dominik falls into the same voyeuristic trap of representing Monroe as the ‘Blonde’ victim at the hands of powerful men in Hollywood, essentially failing to differentiate between Norma Jean and Marilyn Monroe. The problem in reflecting on the actress’s life germinates from the intrinsic actress-sex worker connection prevalent during the age of theatres.

This was to segregate the ‘respectable’ women from the ‘deviant’ ones. The category of the sex worker itself was a discursive one that encompassed the construction of an identity for a woman who was at another extreme of the ‘respectable’ society.

For Monroe, this link was conjoined with the shaping of her identity, leading to the severe sexualisation of her attributes. From her voice to her physical appearance; she became a fetishistic desire for the public; the ‘blonde bombshell’. This enduring linkage between an actress and a sex worker often obliterated the creative skill set that led them to rise professionally in the public realm dominated by men.

Although Blonde is partly fictional and partly based on the lengthy novel by Joyce Carol Oates, it ingrains Marilyn Monroe as a sex symbol once again rather than deconstructing it. The lens of Blonde reduces Monroe as an actress and a performer making her excessively susceptible to the men in power, resulting in a continued and systemic oppression for her that was difficult to escape.

Andrew Dominik’s take on Monroe showcases a somewhat fearful, vulnerable and naive side of her in the quest for mandating a space in public. Dominik’s perception of Monroe extends the actress-sex worker connection that perhaps Monroe faced during her career.

Also Read: Marilyn Monroe And The Sexist Idea Of Sex Symbol

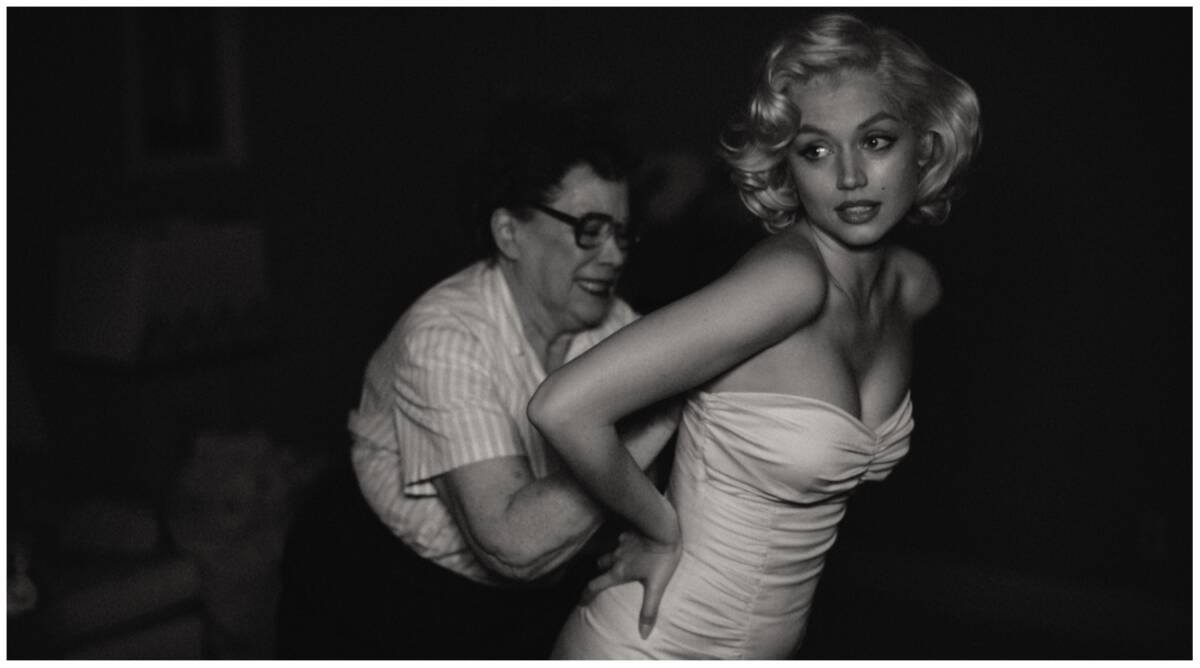

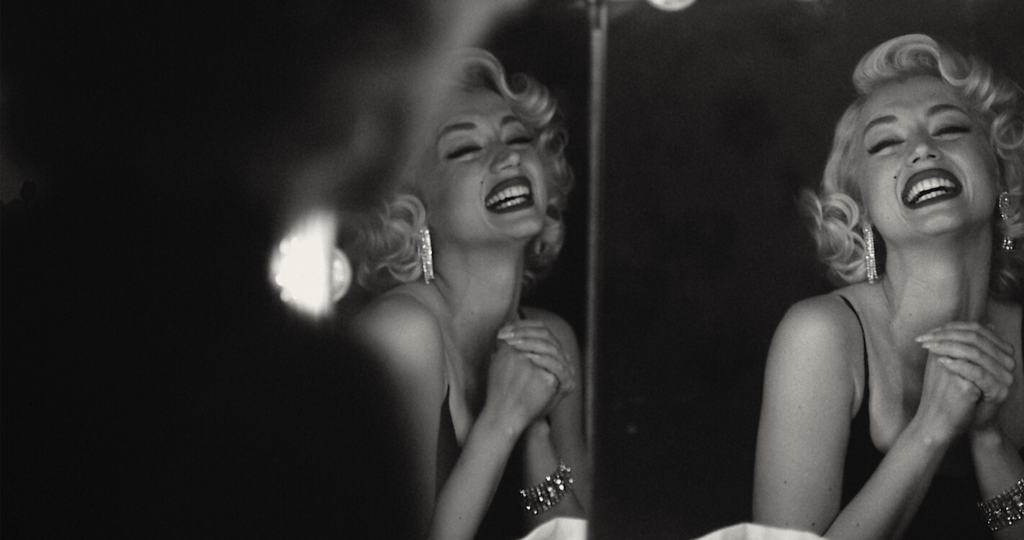

Blonde shapes, nurtures, and redeems Norma Jean by objectifying her. Marked with undoubtedly a stellar performance by Ana De Armas, the Netflix original flattens out the nitty-gritty of Monroe’s life and career, presenting a monotonous three-hour ride of the actress’s abasement. Suppose the constant fear, sexualisation and vulnerability were the only truth for Monroe. In that case, it becomes difficult to explain her excellent career graph, formidable public presence and sheer immaculateness of her performances.

Actress-sex worker connection

Blonde deals with the male ‘gaze’ in a very aggressive and assertive manner, interspersed with objectifying lyrics of Monroe’s musical numbers, often bringing forth the sexual revolution of the 60s of which Monroe was emblematic. The underlying conflation of the actress and the sex worker subliminally shaped Monroe’s Hollywood career.

The actress-sex worker connection has haunted the public thought regarding stage actresses for the longest time due to the general nature of the profession that makes the visible female body a point of significance in forming the actresses’ identity. This linkage often reduces the differences between the occupations, further discrediting the creative labour of actresses and dehumanising the sex worker.

The residue of this social thought discursively shaped Monroe’s occupational identity that actresses are just sexual beings whose position in society is outside the ‘domestic’. Dominik’s perspective is formulaic of a grovelling and screaming Marilyn devoid of creative talents.

Being sexually exploited by the President, Blonde jumps back to the fetus’s montage in the movie’s last thirty minutes. Blonde depicts a controversial take on Monroe’s abortion and an overt portrayal of a mother’s guilt that, by the end of the movie, engulfs Monroe, driving her into insanity.

This partly portrays the public thought of the time noted by Pricilla Alexander, who writes, “It’s better for a woman not to freely explore their feminity and sexuality because this puts them at a risk of being identified as ‘whores’.” The actress and sex worker were both sexualised figures, disentitled of any labour they embodied and exhibited, representing deviant sexual behaviour that endured in social thought even during Monroe’s time.

This linkage dismisses the labour of the actress and the sex worker as illegitimate, outside the purview of ‘respectable’ society. At the same time, the construction of this linkage undermines the economic self-sufficiency and affluence of the stage actresses.

Also read: The Prejudiced And Sexist Narrative of Social Media Giants

During the 60s, despite being the top actress in the United States of America, Monroe struggled to be understood for her labour and skill instead of her sexual attributes constructed by the male gaze. Dominik’s portrayal places Monroe back in this linkage of the constructed categories of the actress and the sex worker, debarring her of labour, skill and talent.

This time she is not the ‘dumb blonde’ of the sixties but has been reduced to just a victim of circumstances that emanated from her overt sexualisation in the public domain. Joseph Roach writes that celebrities have two bodies; one that perishes with death – ‘body natural’ and the other that gets carried on in the public eye – ‘body politic’. The actress-sex worker linkage marked Monroe’s ‘body natural’ during the 60s, and Dominik’s adaptation injects the actress-sex worker connection and its residue into her ‘body-politic’ today.

(In)advertently capturing this conflation, Andrew Dominik severs all the other emotive parts of Norma Jean Baker in conceptualising Marilyn Monroe. In a scene where Monroe is seated inside a theatre with Charles Chaplin Jr. (Xavier Samuel) and Edward G. Robinson Jr. (Evan Williams), viewing her performance and simultaneously involving in a sexual act entrenches this linkage of sexual flagrancy that simultaneously debases and takes away from Monroe’s performance on screen.

Although Blonde is partly fictional and partly based on the lengthy novel by Joyce Carol Oates, it ingrains Marilyn Monroe as a sex symbol once again rather than deconstructing it. The lens of Blonde reduces Monroe as an actress and a performer making her excessively susceptible to the men in power, resulting in a continued and systemic oppression for her that was difficult to escape.

This take on Monroe’s career reflects the actress-sex worker linkage that is latent in the social thought and results in Andrew Dominik serving Monroe as a sexual victim rather than a survivor, actor and producer.

The redemptive trope of motherhood

Blonde consistently tries to represent Monroe’s confidence and stature as a façade in the public eye to hide her fragile inner self. Dominik scrupulously reflects on this fragility of Monroe, who constantly urges to be rescued by men or motherhood.

The trope of motherhood rooted in childhood trauma plays an essential part in the second half of Blonde as an inevitable redemptive solution that can save Monroe from the actress-sex worker category.

After her first abortion, followed by a miscarriage, Dominik’s take on Monroe solemnly reflects her deep remorse shrouded in a consistent urge to become a mother. Having failed to meet her biological goal, Monroe completely loses a grip over reality, as presented by Dominik. Donald Spoto writes how Monroe was utterly conscious of her public self, although childhood trauma had rooted a deep sense of inferiority in her; Monroe’s resilience and constant labour went unnoticed.

Monroe worked relentlessly for social and humanitarian causes, often providing much-needed entertainment through her skilful performances to troops in Korea. All these events do not even remotely feature in Dominik’s adaptation.

Being sexually exploited by the President, Blonde jumps back to the fetus’s montage in the movie’s last thirty minutes. Blonde depicts a controversial take on Monroe’s abortion and an overt portrayal of a mother’s guilt that, by the end of the movie, engulfs Monroe, driving her into insanity.

The actress-sex worker linkage has endured in social thought much more metaphorically than in the age of theatres. This linkage demonises the occupational categories for women; however, Blonde clandestinely highlights the danger of this social thought as Dominik’s lens of portrayal rarely wavers from the narrative of sexual victimhood and the idea of how badly Marilyn Monroe had to be ‘rescued’ from the men of Hollywood.

Andrew Dominik almost deliberately reflects Marilyn Monroe’s fear and fragility in Blonde, which hinders her from possessing any other identity. The movie pushes Marilyn either to be a daughter and find daughterly love in all her relationships or the inability to become a mother.

Traditionally, the roles for any ‘respectable’ woman are of a daughter, a mother and a doting wife; Blonde exactly brings this forth in defining Monroe camouflaged in a redemptive tale of controversy. Blonde tragically memorialises Marilyn Monroe urging her to be remembered for the atrocities suffered instead of the triumphs.