In the history of patriarchy, tales of legendary women have been passed down in whispers almost as if those tales are sacred and are meant to be held onto carefully, lest they shatter and fade away.

Lakshmibai Tilak’s is one such name that women have heard growing up in their Marathi houses, either as a warning or as an inspiration, because she was a pioneering figure, not only in the literary world which in itself was an outstanding achievement at that age, but also in her varied struggles against patriarchy while trying to establish herself as an independent woman with a voice and opinions of her own in a nation ripe with strife and chaos.

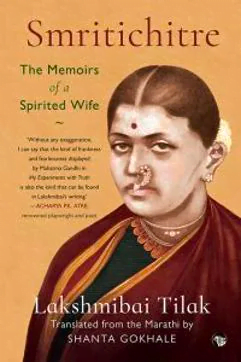

The account of Lakshmibai Tilak’s life comes mostly from her magnum opus, her autobiography titled ‘Smritichitre’ which was published in a serialised format in four parts in the magazine Sanjivani from the years 1931-1936.

The life of Lakshmibai Tilak

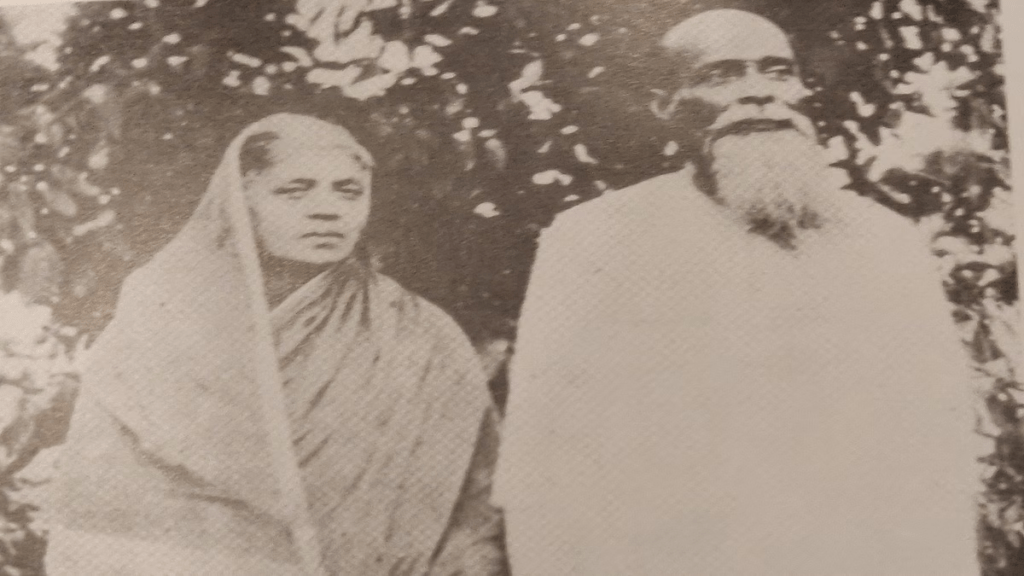

Lakshmibai Tilak, then Manakarna Gokhale, was born in 1868 to an orthodox, dominant caste family in Maharashtra. At the very young age of 11, she was married off to a much older man named Narayan Waman Tilak, a poet and social reformer, whose household was dominated by patriarchy and orthodoxy, very similar to her own home.

Tortured verbally, physically and mentally by the men in her life – her father, her husband, and her father-in-law, Lakshmibai Tilak, nevertheless, managed to carve out a path of her own accord in her journey of life, an act that must have taken a lot of strength and courage.

‘Smritichitre’, a Sanskrit word for Memory Sketches, translated into English first by Josephine Inkster and published as ‘I Follow After’, starts with Lakshmibai Tilak’s childhood at her parents’ home. A landscape of the lives of women in orthodox Indian society is portrayed poignantly in the book. The patriarch of the household, Lakshmibai’s father, is tyrannical and wraps up the environment of the house in imposing practices and rituals. The women, obviously, are made to suffer the worst end of that stick

Taught basic Marathi by her husband, Lakshmibai Tilak went on to write prose and poetry even while doing various odd jobs to sustain herself and her family after her husband’s death. She even completed the work her husband was unable to finish when he was alive, an epic titled ‘Khristiyana’ concerning tales of the Christ’s miracles and his work on Earth.

What is perhaps remarkable among all of this is Lakshmibai Tilak’s tenacity at surviving against all odds. Despite the turmoil she faced, she never gave up on artistry and a life devoted to the arts. Her husband converting to Christianity was one of the biggest challenges she faced in her life and even considered giving up her own life at a particular moment in time.

She was so much in pain, that she wrote in her autobiography, “My ears were buzzing. I could see no way open before me…They began to try to open my teeth, and pour a little medicine between them. I was aware of everything, but lay like a log of wood. My tongue was drawn together and covered with prickles which did not go away for a whole month. Bhiku’s sickness vanished, and rolling up her bed she now spent night and day standing beside me. She had to wait on me hand and foot. I could only lie [down]. She even had to brush my teeth. From time to time I was given milk and butter milk. Many days later my strength returned a little, and I began to sit up in bed. Now were the flood gates of my tears opened. I cried continuously. My tears could not be damned, unless indeed there was respite in sleep. I spoke to no one.”

Lakshmibai Tilak eventually converted to Christianity later on, after struggling with her loyalty to her husband and her emotions regarding her own religion and culture, and traveled to many places with him before his death.

In all of this, Lakshmibai was unflinching and unapologetic. She was never ashamed of the details of her life’s adventures, never shied away from honesty, and her works reflect that same tenacity and rebelliousness of character.

At an age in a soon-to-be decolonised nation, where women were hardly provided with basic education let alone an opinion, Lakshmibai Tilak’s life and unique voice is awe-inspiring. Almost unbeknownst to her, her autobiography provides a detailed glimpse into the lives of women during the times India was aiming for independence. Lakshmibai’s life opens up a nuanced picture of family, society, love, religion, social reforms, and most importantly, the struggle for independence.

Also read: Malati Bedekar: Contemporary Marathi Literature’s First Feminist Writer | #IndianWomenInHistory

Lakshmibai Tilak’s body of work: Narratives defying patriarchy and holding a mirror to the times

‘Smritichitre’, a Sanskrit word for Memory Sketches, translated into English first by Josephine Inkster and published as ‘I Follow After’, starts with Lakshmibai Tilak’s childhood at her parents’ home. A landscape of the lives of women in orthodox Indian society is portrayed poignantly in the book. The patriarch of the household, Lakshmibai’s father, is tyrannical and wraps up the environment of the house in imposing practices and rituals. The women, obviously, are made to suffer the worst end of that stick.

Lakshmibai Tilak weaves her narrative masterfully, with small details of how women defy patriarchy in their own ways and these incidents are put forward like small tales meant to be handed down as advice to future generations of women subjugated under male domination.

It is a terrifying picture, at times morbid, but the strength of the women shines even through the darkness. Life after marriage is also handled by Lakshmibai Tilak in her autobiography and the flair of her thoughts as they take shape through her writing style is at its best because it would be an understatement to say that her relationship with her husband was complex.

Lakshmibai Tilak’s husband was generous, supported her literacy, but was also the person who pushed her down the stairs while in a fit when she was seven months pregnant. “Possibly because laughter was the most efficient strategy she could use, but possibly also because only the veil of humour enabled the chronicling of such experiences, Lakshmibai describes the incident as though it were a hilarious affair, though she also comments, in passing, “without doubt that day my infirmity brought me face to face with death. I was saved by so small a margin.” The chapter concludes, “Tilak wrote a farce about his own temper. It was left half-finished.”

Lakshmibai Tilak loved her husband but was not blind to his cruelties. Her commentary is scathing but never once bitter. It accepts the greyness of the people and the world around her. In part four of her autobiography, she writes, “Ever since I was a child of eleven, I had lived with and by the side of Tilak. We had lived apart for five years in between, but not for a single moment of those five years had Tilak moved from before my eyes, nor I from before his. What I am today is because of him. If he wished to reach a goal, I was there to help him to it; if he wrote a poem I was there to sing it; if he had to beg, I was there to carry the begging bowl”.

These lines acknowledge Lakshmibai Tilak’s love for her husband ,but it also acknowledges her part in his life, and her efforts in sustaining their lives, which is why when she writes, “Tilak was like a steam engine, running on his own power, and I, like a carriage that ran on the speed imparted by the engine. Once I had worked up momentum, though, there was no stopping me. But now he who had held the strings of my life had left me. A new world sprang up around me. A new life began.”, we are left assured of Lakshmibai coming out victorious of life’s challenges.

At an age, therefore, where women’s narratives in history were as rare as gemstones, Lakshmibai Tilak’s writings provide us with glimpses into the lives of women at a particular moment in history. In the fight for independence, on the path towards decolonisation, mostly men’s narratives are highlighted, but Laksmibai Tilak’s writings are revolutionary because aside from bringing to light the domestic world, it also encapsulated the ongoings of the external world and the effects and consequences it had on human minds

Instead of feeling melancholic and helpless, Lakshmibai Tilak started living her life even more fervently, with a stronger, vivacious zeal. Tilak’s struggles with her orthodox father-in-law are further instances of the inhumane torture women faced in the name of patriarchal control.

Lakshmibai describes one such instance in the book- “Whenever we quarreled over oil and shikakai, he would tell me this story: ‘Once we had run out of firewood. My wife was pregnant. Even then I made her chop wood. Why should I show concern for you? My wife never answered back. When she realised she had run out of some foodstuff, she would place the remains before me without a word. I understood that she was running out of the stuff. But today’s girls have become very arrogant. You’ll never learn how to behave with elders.’For ‘those’ three days of the month, I was left to starve. Mamanji would cook only for himself. He would cook for all of us only when Mr Tilak was around. On those days I had to sit in a dark room. I was very scared of the dark. But gradually, I lost that fear.”

Despite all of this, Lakshmibai Tilak also talks about a few moments when her father-in-law showed her kindness when her husband used to disappear for months on end. What is life if not the parallel existence of such contradictions? No wonder then, her writing is as engaging as it is. Other than the autobiography and the epic, Lakshmibai Tilak also wrote a collection of lyric poems titled ‘Bharali Gagar’.

At an age, therefore, where women’s narratives in history were as rare as gemstones, Lakshmibai Tilak’s writings provide us with glimpses into the lives of women at a particular moment in history. In the fight for independence, on the path towards decolonisation, mostly men’s narratives are highlighted, but Laksmibai Tilak’s writings are revolutionary because aside from bringing to light the domestic world, it also encapsulated the ongoings of the external world and the effects and consequences it had on human minds.

In modern Indian literature, Lakshmibai Tilak’s autobiography is one among the few other autobiographies written by women, and her depictions of poverty, domestic problems, patriarchal domination and a nation’s inherent orthodoxy as it moves towards independence, are unparalleled and entwined with her humour and engaging style.

Also read: K Saraswathi Amma: The Pioneer Of Feminist Literature In Malayalam

About the author(s)

Sayeri Biswas recently graduated with a bachelor’s degree in English from St. Xavier’s College, Kolkata. Whether it’s philosophically

contemplating life or gushing about the most recent book/series she has indulged in, she is always up for a deep conversation. Literature is the great love of her life, and in the future, she hopes to continue talking about all art forms as passionately as she thinks

about them.