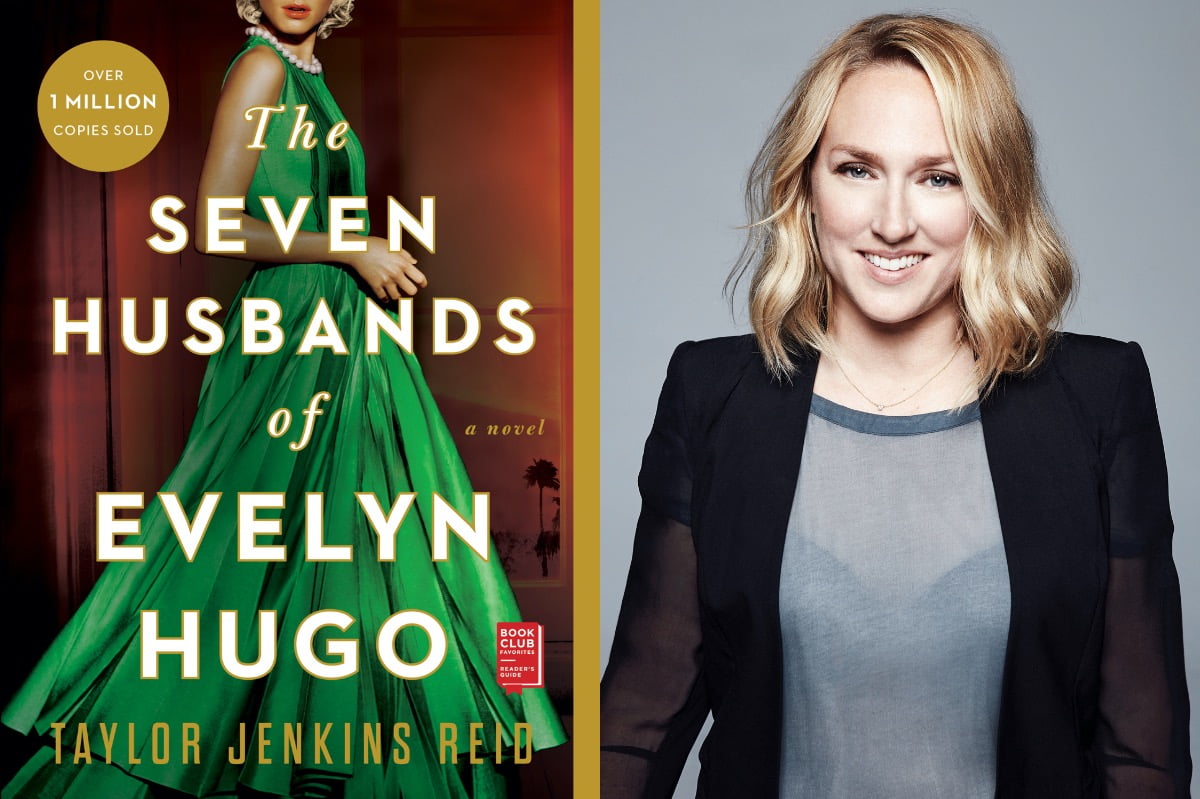

Oscillating between the 80’s of the past and the present, Taylor Jenkins Reid’s 2017 Young Adult Historical Fiction novel The Seven Husbands of Evelyn Hugo tells the story of a fictional Old Hollywood star, Evelyn Hugo, recounting her life and relationship with a journalist before her death.

We approach this story through the eyes of the journalist, Monique Grant, as she comes to form a convoluted bond with the complicated actress as she attempts to document her life’s story for her. Though Monique is the main character, she has little substance to her outside of serving as a conduit for Evelyn, who is an amalgamation of real life Old Hollywood actresses Elizabeth Taylor, Rita Hayworth, and most notably, Marilyn Monroe.

In this way, The Seven Husbands of Evelyn Hugo ambitiously sounds as a queer revisionist take on Old Hollywood within a fictionalised setting. It is almost insulting when you’re reminded that among the fictitious revisions made, a fictional lesbian, Celia St. James, is awarded as the Best Actress Oscar in 1982 in place of real life queer actress, Katharine Hepburn.

Telling, not showing

Perhaps, Reid’s matter-of-fact prose was not my cup of tea, but The Seven Husbands of Evelyn Hugo is ultimately a collection of 80’s Hollywood aesthetics and landscapes that run through a simplistic YA formula until it is no longer discernible from any of its counterparts within the genre, regardless of the potential that the original idea and subject matter held.

We navigate this story with the author keeping a tight hold on our hand, in what we are to understand of, or feel from, these characters and the events that unfold. Critics argue that Reid creates “complex, likeable characters” but few instances within the book offered its characters deeper complexity than what we were presented with from the outset.

Evelyn Hugo is presented as a predominantly white woman, with a certain “best of both worlds” quality, as it is the idealised image of the biracial woman from an imperialist lens. Throughout the course of the novel, Evelyn easily and comfortably passes for a white woman and reaps the benefits of this ability without question, until Reid decides that her Cuban heritage is of relevance to a point she would like to make on being biracial.

The premise of the book centres around the bittersweet love story, between two Old Hollywood actresses, the titular Evelyn Hugo and Celia St. James. There is a little mystery to the development of their romance, as would have been expected, given the plot. We could attribute this to the marketing surrounding it, leaving no room for doubt in who would have been the love of Evelyn’s life out of the suitors lined up for her. Given this fact, Reid lazily establishes this fact within the first few chapters itself and leaves a little room for the reader to anticipate in the novel. This trend of telling, instead of showing, continues in many other aspects as well, as though the writer has given up any pretence of intrigue that draws us to fiction in the first place.

We know Evelyn and Harry are best friends because each exchange between the two will include a verbal confirmation between the two that they are, as such, best friends. This is despite us seeing no real development of their dynamic throughout the course of the novel that would lead us naturally growing to truly care for, and root for, their bond.

We know Evelyn is notably “glamorous” by conventional standards as this is established and reiterated to us through the prose, as well as in the dialogue exchanged between the characters in regards to Evelyn and in Evelyn’s internal dialogue itself. There is thus a great deal of importance placed on her conformity to the feminine beauty ideal.

Making a statement

Evelyn’s aforementioned “glamour” is first emphasised in drawing attention to her breasts, her hair, and the “bronze” tone of her skin, by the protagonist, Monique, as she studies pictures of Evelyn online. The emphasis placed upon these identifying features paints her as the image of ethnic ambiguity. She is still presented as a predominantly white woman, with a certain “best of both worlds” quality, as it is the idealised image of the biracial woman from an imperialist lens.

Celia St. James who, as a lesbian, is repeatedly villainised by the narrative for not understanding bisexuality to the satisfaction of the author and her demographic. She is also heinously compared, in her desire for Evelyn, to heterosexual men.

Throughout the course of the novel, Evelyn easily and comfortably passes for a white woman and reaps the benefits of this ability without question, until Reid decides that her Cuban heritage is of relevance to a point she would like to make on being biracial. Her identity as a Cuban-American woman is continually isolated from the context of global politics in regards to the Cuban-American international relations, though Reid makes it a point to interweave the Stonewall Riots into Evelyn’s identity as a queer woman.

A large majority of this book’s “statements” on socio-political identities are largely delivered within the dialogue as though they have been cherry-picked from an Instagram infographic or a Twitter thread, making it increasingly obvious that Reid’s greatest concern with these characters is to make them better mouthpieces to fall into line with her own politics and beliefs, regardless of whether they are characteristic of who speaks them or relevant to the ongoing scene.

Also read: Mason Deaver’s Book ‘I Wish You All The Best’ Unpacks The Self-Assertion Of A Non-Binary Protagonist

The unrealistic phrasing of sentences, unconvincing motivations of characters, and a complete lack of nuance in many of these important conversations pertaining to domestic abuse, sexual identity, and so on, are egregious in how they fail to utilise the medium of literature to amplify the core message. Instead, we receive regurgitations of slogans popularised on the Internet by the very audience targeted for this book.

The misrepresentation of Queer women

There were a number of integral elements towards understanding Evelyn, and the interiority of her character, that are glossed over by a narrative which is more interested in selling you, her thoroughly unconvincing romance with Celia St. James.

Celia St. James who, as a lesbian, is repeatedly villainised by the narrative for not understanding bisexuality to the satisfaction of the author and her demographic. She is also heinously compared, in her desire for Evelyn, to heterosexual men. I grapple with the understanding of how anyone can interpret any collusion between lesbians and heterosexual men in how they view women, and in their dynamic with bisexual women. Even Evelyn’s attraction towards women is utilised in moments to make her feel “at par” with men as she comes to collaborate with them in framing her sexualisation on screen as an “empowered” portrayal.

Same-sex attraction is simultaneously and paradoxically posited as a uniting and dividing force between queer women and heterosexual men, where a lesbian relationship is written within the mould of a heterosexual one, having no unique concerns outside the societal discrimination and the fear of it.

When this is the most widely read and popularised book amongst young lesbian and bisexual women today, it is somewhat disconcerting to watch the representation be lauded as the ideal for queer women when it is riddled with uninspired and unempathetic portrayals of queer women.

Also read: A Critique Of The Queer Young Adult Genre

With lesbians being equated to straight men as a way to empower bisexual women, in addition to a poorly written love story that asks you to root for it not for the sake of the love story itself but by virtue of them both being women, it fails to create a compelling narrative for queer women to explore their own stories and identities by seeking to do little more than “represent” queer women in name.

The feminist themes lack nuance and depth, announcing themselves at every turn but offering nothing to its audience beyond an instagrammable quote here and there. Queer womanhood is deeper and more complex than how heterosexual woman, despite their allyship, frame it to be.

About the author(s)

Tanya Roy is a 20-year-old student at FLAME University in Pune, with a major in Film & Television Management and a minor in Literary & Cultural Studies. She is interested in critiquing and analysing art in its different mediums through a feminist lens and is an avid reader of feminist and other sociocultural theories.