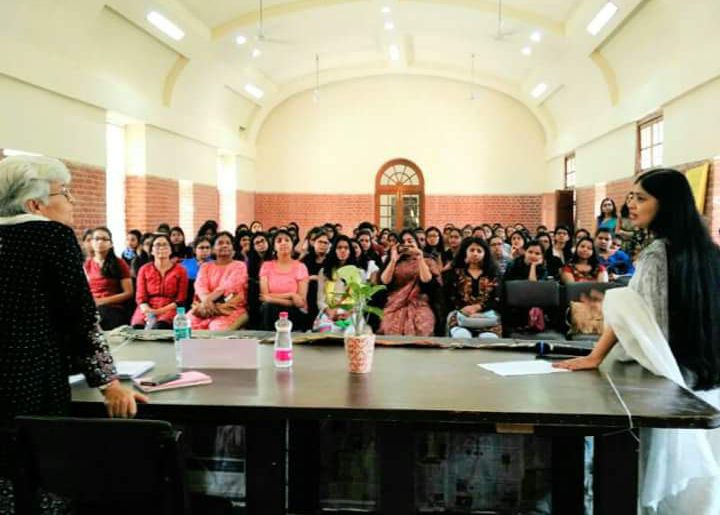

The imposing red brick walls with barbed iron fencing of Miranda House in the North Campus of Delhi University, form a literal wall of protection and a metaphorical wall of protest against the male gaze. Inside the gates, there is a marked absence of behaviour, colored by the consciousness that male presence inevitably brings.

Despite the solidarity that comes from students as a response and reaction to patriarchy, this concord is marred by the concerns and construction of class, caste, religious and regional identities of students. There exist sharp divisions between the students, a hierarchical structure that mirrors the Indian society at large. The intersection of identities despite the underlying commonality of gendered oppression creates unequal power relations between the students, clearly visible social groups and discrimination.

The imagination of a women-only academic space, as it is historically placed, needs to be contextualised in the relevant time frame. The evolution of women’s colleges through years along with the growing developments and assertions of the feminist movement is essential to understand them today. This imagination is reworked by each succeeding generation in creating spaces that are more inclusive and conducive to women and the academic performance of gender minorities.

Women and minority colleges are persistently pushing the boundaries of socially constructed ideas of gender, its roles and norms. A women and gender minority college constantly revisits, rethinks, reinvents and renounces the ideas and conceptions of gender with each influx of new batch. The same can rarely be said for heteronormative patriarchal set-ups. While it might be said that, traditionally, women’s colleges offer a more inclusive environment for queer and transgender students, it would be false to imply that it is a perfect space, or even a good one. From discriminatory admission procedures to transphobia and homophobia within the campus, they reflect the social biases despite claiming to offer the most progressive space.

Relevance?

The lack of male presence does not imply a lack of patriarchy itself. In a patriarchal society, elements and aspects of patriarchy are everywhere, however, the absence of the male gaze and a direct confrontation with the most active proponents of patriarchy, that is men, whether through their passive reaffirmation of sexist stereotypes or proactive predatory behavior, creates time and energy that can be alternatively spent on the development and progress of a parallel academic discourse by women and gender minorities.

Questioning the relevance of women and gender minority institutions in the twenty-first century without challenging the relevance of thriving patriarchy in this decade, are passive stances that put up the pretence of ‘political correctness’ without the necessary sensitivity or subtlety needed for understanding the complexities of gender and higher education.

As a scholar from the Radcliffe Institute (a formerly women’s institution that merged with Harvard in 1999) said to the Bangor Daily News in 2002, “if women’s colleges become unnecessary, if women’s colleges become irrelevant, then that’s a sign of our [women’s] success.”

The precondition for the state of affairs that will set in motion the process for the irrelevance of women’s colleges, is the downfall of patriarchy which seems as far off in 2022 as it did in 2001.

Negating the need for safe spaces for women and gender minorities without attacking the system that actively threatens and discriminates them; And questioning the relevance of women and gender minority institutions in the twenty-first century without challenging the relevance of thriving patriarchy in this decade, are passive stances that put up the pretence of ‘political correctness’ without the necessary sensitivity or subtlety needed for understanding the complexities of gender and higher education.

In an ideal society, perhaps, women and gender minority colleges may become irrelevant and even counter-productive, but today’s society, even by the most buoyant imagination cannot be nearly construed as ideal. Therefore, the question of relevance itself becomes irrelevant.

The male gaze

How women and gender minorities use space is directly influenced by male presence, which consequently implies male gaze. By use of space, one means mundane everyday actions, such as lying down in lawns, hanging out at the canteen, dance practice sessions and more become easier without the weight of male gaze on them. Campuses and classrooms devoid of male gaze, will foster better academic performance from its students. It must be noted, however, that the campus that imagines a male gaze-less space is not always successful, if only due to the ever-resourceful never-ending barge of the toxic masculine penchant for causing exasperation. The incidents at Miranda House earlier this month, Gargi in 2020 along with the examples of harassment at LSR and other women and gender minority colleges of Delhi University, the male imagination of such campuses seem to be the inverse of the female imagination.

Academic Performance and the lack of proper inclusion

The idea of single-sex classrooms is exclusionary and colleges that houses students from various gender identities and sexual orientations, not limited to cis-het women, are not officially referred to as such, due to the administration’s unsurprising lack of awareness and sensitivity, not to say blatant transphobic and homophobic sentiments. Kalindi College sets an admirable precedent in this matter by establishing a Transgender Cell to sensitise the students, and collaborating with a queer feminist resource group to hold counselling sessions.

However, there is a lack of clarity regarding the admission procedures for women’s colleges, and the administration’s take on the same. Regardless, a long fight to gender equality and rights will be required to set the first step towards a more inclusive ‘safe space’ for gender minorities.

As minority groups that are ill-represented in every office of power, industries and employment avenues, popular media and more, the term gender minorities cannot be dismissed on naturalistic assumptions that women form half of the population.

The term ‘gender minority’ is often misunderstood to mean, women being called minorities (which is usually countered with crude numbers like women form 50% of the population) when it in fact refers to a social group that faces relative disadvantages when compared to the dominant social group. The disadvantage can be in terms of number (as in, gender minorities are fewer in number) but also refers to the structural inequality against minority groups in the social and political framework.

As minority groups that are ill-represented in every office of power, industries and employment avenues, popular media and more, the term gender minorities cannot be dismissed on naturalistic assumptions that women form half of the population.

Discrimination and social biases

Despite the solidarity that comes from students as a response and reaction to patriarchy, this concord is marred by the concerns and construction of class, caste, religious and regional identities of students. There exist sharp divisions between the students, a hierarchical structure that mirrors the Indian society at large. The intersection of identities despite the underlying commonality of gendered oppression creates unequal power relations between the students, clearly visible social groups and discrimination. The solidarity formed stands to mean nothing at all if the students themselves are divided and discriminated on the basis of their class, caste, religion, region and linguistic background. A safe space cannot exist in isolation from society or social realities, the spaces themselves, however progressive their outlook, consist of individuals from the society and therefore will reflect the social realities. In order to maintain the space as safe, active affirmation of progressive values and radical steps to counter regressive notions are essential, without which the space fails to remain ‘safe’.

It is prudent to concede that however pleasing the imagination of women and gender minority colleges as safe spaces be, they are but pockets of escape. The women and gender minority colleges of Delhi University, like Miranda House, Lady Shri Ram College, Indraprastha College for Women, Gargi College and others, are islands of feminist and queer resistance in mostly sheltered secure sectors (whose degree of security is often compromised, as evidence suggests), clustered together in Delhi against an ocean of patriarchy. The dismissal of women and gender minority educational institutions is then refusal to acknowledge the academic excellence that is possible without overt male interference or participation.

As previously mentioned in the essay, the lack of constant surveillance from the male gaze is liberating. However liberating implies that one is freed from the situation that restricts one, while the systemic reason behind the restriction still exists and indeed thrives, perhaps not in the specific time and space that women and gender minority colleges campuses provide to their students. It is therefore liberating in a limited conditional sense, once you step outside the gates or finally graduate, the jarring reality of society hits you like a truck.

Women and gender minority institutions will remain relevant till patriarchy is, and will be dismantled, as and when the last nail in the coffin of patriarchy is hammered in.