In the last 6 months, we saw three movements related to the Hijab issue. The Hijab row in Karnataka, the Taliban’s Hijab decree and the protest against Hijab in Iran. While the former argument revolves around, how hijab is oppressive as well as patriarchal for Indian women, the latter two revolves around the enforcement of hijab on Afghani and Iranian women.

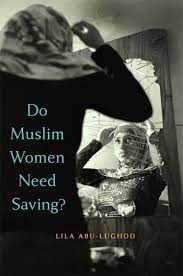

“Do Muslim Women Need Saving is my attempt to figure out how we should think about the question of Muslim women and their rights.”

Lila Abu-Lughod

The arguments were contrary but all have three things in common: first, it’s highly political, second, they ignored women’s choice & their voice and third their core argument was based on “saving women”- In India, women were to be saved from oppression (specifically by their religion Islam) while in Afghanistan and Iran, women are saved from ‘modern/western culture’. Now the question that arises here is- do women really need saving? The answer can be found in Do Muslim women need saving? authored by Lila Abu-Lughod.

Do Muslim women need saving?

The Book “Do Muslim Women Need Saving is my attempt to figure out how we should think about the question of Muslim women and their rights,” writes Lughod. Lila Abu-Lughod is a Palestinian-American anthropologist. She is currently a Professor of Anthropology and Women’s Studies at Columbia University in New York. Her work is strongly ethnographic and primarily based in Egypt, she has been focusing on three broad issues: the relationship between cultural forms and power; the politics of knowledge and representation; and the dynamics of women’s and human rights, global liberalism, and feminist governance of the Muslim world.

In this book, Lughod tries to bridge the gap between how Muslim women are portrayed as hapless in western writings and how they are as an individual woman, that she had known through extensive ethnographic engagement in the day-to-day realities of Muslim women’s lives in Egyptian villages. While she draws her analysis heavily on her experiences living in some small communities in Egypt, she clarifies that she does not claim that women whose lives she analysed are representative or can stand in for all others.

The work points to the importance of rising attention to Muslim women’s rights in the contemporary context of international interventions and shifting politics that place a heavy critical lens on Muslims. Lughod connects her analysis to the larger institutional framework of international feminism, human rights, and NGOs that create institutions for ‘saving’ Muslim women.

The book is a detailed condemnation of global Western ideology regarding the role of Islam in oppressing women in Muslim-majority countries. The book’s message is based on the idea that Western

authors/activists/feminists must reconsider commonly held, normative assumptions regarding the role that Islam may or may not play in the repression of women in predominantly Muslim communities and

nation-states. Instead, Lughod argues that variables such as government, politics, and economics are more closely linked to women’s oppression and she recommends that women’s rights must be re-evaluated and re-structured in order for the Muslim community to attain actual women empowerment.

Beginning with an anthropologist’s perspective, Lughod introduces the significance of individual views and their value in regard to women’s rights. This is accomplished by narrating the story of a Muslim Egyptian woman, Zaynab, who declared that Muslim women are oppressed not by Islam, but by the government. This anecdote, however brief and unfinished, is what permits the book to carry into her study of various preconceptions and misrepresentations about Muslim women, as well as the Muslim community as a whole, particularly after the 9/11 attacks.

Source: Teaching Culture

She illustrates how the veil (hijab/niqab) manifests itself differently in different countries and communities. In the Arab culture, it represents morality and respect, whereas, in the Western world, it represents oppression and the lack of voice. Lughod explains that it is all a matter of perception. According to her, the agenda to save Muslim women is part of a larger strategy in which the West demands that they look elsewhere for issues other than their own. In particular, Western-issued writing focusing on global gender discrimination consistently ignore the rampant rape culture, domestic violence, and workplace gender discrimination that regularly takes place in Western countries such as the U.S. The global campaign for women’s rights has turned into what Abu-Lughod refers to as a “moral crusade,” which has pitted the West against the Islamic ‘other’.

Lughod puts an emphasis on the importance of acknowledging and thoughtfully accepting the significant cultural differences between Western and non-Western conceptions of individuality as well as respect for cultural norms that are based on non-Western values. She emphasises the significance of recognising Muslim women’s autonomy rather than seeing them as helpless symbolisms rendered powerless by their hijabs, niqabs, or burqas.

She questions the symbolism used in connection with subjects like modern slavery and critiques popular written narratives of survivors, which she refers to as “pulp nonfiction”. She tells the personal narratives of several common Egyptian women, proving them to be far more than basic accounts of oppression, and offers an interesting and unusual interpretation of Muslim feminism.

Lughod portrays the concept of honour crimes as overdramatised. She discusses public debates about honour crimes which unfold the illusion of saving Muslim women, and collapse into ‘Islam’ rather than addressing the causes of violence. Her discussion of ‘Seductions of the Honour Crimes’ is an outstanding case study that explores how racism operates to stigmatise Muslim minorities in the West. Lughod connects her analysis to the larger institutional framework of international feminism, human rights, and NGOs that create institutions for ‘saving’ Muslim women. She points out that this international gender

equality and human rights infrastructure is a powerful governing instrument that all too often simplifies complicated challenges when it comes to rights.

Ultimately, the work points to the importance of rising attention to Muslim women’s rights in the contemporary context of international interventions and shifting politics that place a heavy critical lens on

Muslims. In her analysis of such crucial matters as the politics of the veil (hijabs/niqab) and honour killings, Lughod puts an emphasis on the importance of acknowledging and thoughtfully accepting the significant cultural differences between Western and non-Western conceptions of individuality as well as respect for cultural norms that are based on non-Western values. She emphasises the significance of recognising Muslim women’s autonomy rather than seeing them as helpless symbolisms rendered powerless by their hijabs, niqabs, or burqas.

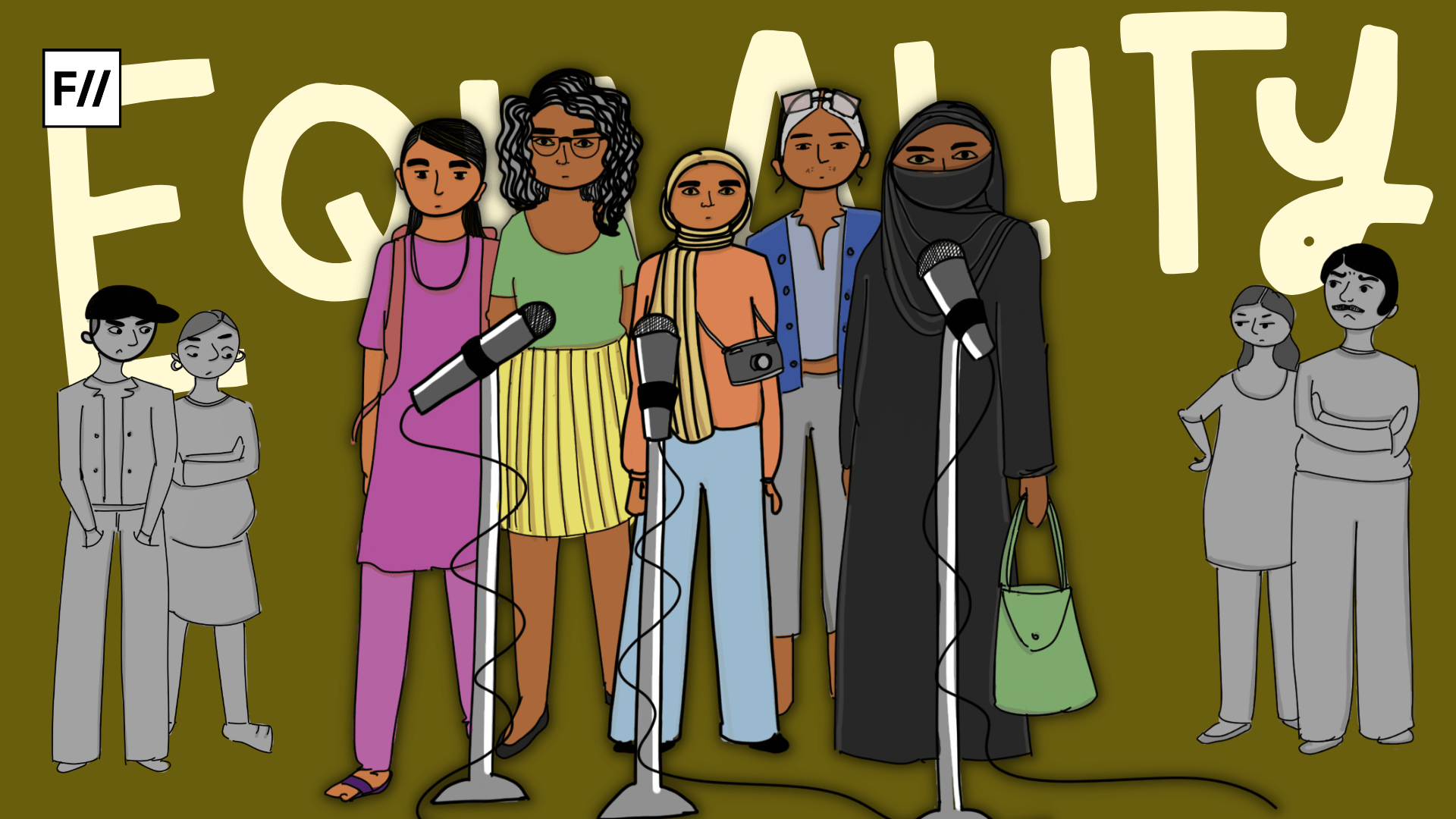

Lughod is able to make a concise and clear argument regarding Muslim women by understanding the complexities and undertones of individuals who are misunderstood in the world. The notion that it is the Western world’s or men’s responsibility to save the Muslim woman is inaccurate and wrong. What Muslim women in particular and women in general, need is equality, freedom, opportunity, involvement, choice and voice.