In the year 2021, Manjima Bhattacharjya, author of Sarpach Sahib, released her latest book Intimate City, which is an insight into the world of sexual transactions post-globalisation in the city of Mumbai. The book examines how technology and the internet have changed the landscape of intimate relationships and private spaces.

The author also explores the changing concept of sex work- from prostitutes to posh escorts, girlfriend experience to massage boys, the entire concept of sexual intimacy and how it intersects with caste, class, and socio-political entities in the post-globalised world through her work. Bhattarcharjya’s book also delves into the concepts of consent, choice, and possessing agency. The author was involved in the Indian women’s movement for over two decades.Her areas of expertise include gender and sexuality, as well as labour and the body.

The characters, geographies, economies and society in Manjima Bhattacharjya’s book , ‘Intimate City‘, give the impression of complex ‘embeddedness’ into each other. This embeddedness is what defines it as something not fitting the conception of a ‘free market’ as we know it. Instead, ‘sex work‘ or what Bhattacharjya calls ‘post-industrial sexual commerce‘ in India, is a strictly regulated, coercively consented and highly diversified plethora of class, caste, region and at its core, a ‘traditionally gendered model of sexual citizenship’: the heteronormative citizen.

Girlfriend Experience and Massage Boys of Mumbai

Bhattacharjya moves to chronicle exclusions in geography, law, class, gender, caste and economics that society goes on to impose upon sex work. The work is aimed to broaden the understanding of sex work in particular, but the politics of intimacy in general post-globalisation still functions on patriarchal and caste-class-based lines even in the most intimate of spaces.

She visualises the women and the men in non-traditional roles as buyers and sellers of the ‘Girl Friend Experience‘ or ‘Massage Boys‘, who go beyond the traditional image of the sex worker to fulfil the role of ‘cultured companionship’ for the night, with hobbies and personality traits like swimming and reading to match the intellectual partner being served! The image she builds of the modern sex worker is beyond the ‘victim but criminal‘, as the law portrays in India, that of a ‘caregiver‘, a source of the unpaid care worker in a capitalist economy built to suck the life out of its participants.

Also Read: FII Interviews: Dr Manjima Bhattacharjya, The Author Of Intimate City

Where does the book stand on feminist debates on sex work

Bhattacharjya quickly situates herself among the feminist debates on ‘global sex wars‘. She rejects both stances, the abolitionist stance on sex work as an abject exploitation of and violence against women. She also complicates the ‘sex as work‘ stance taken by other feminists, arguing for sex work to be seen as another form of marginalised labour in a neo-liberal context. Instead, she looks at the voices of sex workers themselves, who place their work outside this ‘violence-work‘ binary, to see it as equivalent to an intimate and almost household-like care work where women service the needs of men without agency.

Two voices that Bhattacharjya brings to this debate situate the understanding of sex work among those working in it; Lorelei Lee, a sex worker and feminist artist who reveals how sex work is neither purely exploitative nor purely empowering as it is made out to be. She states that even the silo-based understanding of sexual labour as ‘labour‘ stifles the discussion to a calculus of sex work as productive or empowering alone.

She shows that this branding of sex work as ‘work‘ is necessary but not sufficient. Individual experiences and wider contexts impinge and affect the implications and narratives of sex work too, and they need to be analysed before drawing any conclusions.

The second voice is that of a female escort whose name has been altered for the piece. She details that the narratives for most women entering the ‘escort service‘ in India are extraneous circumstances and needs. They enter this field in some form of push from the outer world. And even though there is some element of consent that they have now begun claiming, the lack of networks and solidarity make it an occupation carried out in conditions of precarity and risk.

This absence of a clear black or white on sex work being violent or safe, consensual or coerced, empowering or exploitative, constraining or liberating, complicates the view of it and at the same time aims to introduce the reader to perceive the deeper connotations of contexts rather than commit to just one form of imagining sex work.

The legal and geographic exclusion

Taking the example of the ‘geographies of intimacy‘ of a city like Mumbai, Bhattacharjya asserts how laws, morality, needs and patriarchy all come together to force sex work into the margins and greys of a society. Beginning with the need for satisfying ‘sailors and soldiers‘ in a colonial port city, Mumbai’s ‘red light’ areas moved from being covertly tolerated to being ignored and later being directly challenged by various institutions of socio-politics of the city.

The respectable courtesans of pre-British rule lost patrons and were reduced from being performers to being purely bodies held up for the satisfaction of a particular class – sailors/soldiers pre-independence to migrant labourers and mill workers post-independence. The state used limitation and demarcation of a specific geography, that of Kamathipura, for ease of regulation and surveillance over the area. One can’t help but visualise an element of power used to surveil, control and administer ‘sex as any other form of social activity’ which must be ‘kept in order’.

Post-independence, the regulatory view quickly shifted from nuisance toleration to health and safety, with Acts on Contagious Disease Prevention and AIDS regulation being used to justify police raids, arrests and frequent troubling of all involved in sex work by the police and the state in general. Another agenda that was added as a prism of viewing sex work by the state later was that of anti-trafficking and rescuing minors. Here, Bhattacharjya’s examination of the narratives and expositions behind police raids and court proceedings is illuminating.

Also Read: Kamathipura’s Women Demand ‘Work Without Stigma’: Is The Apex Court’s Judgment Enough?

The Social Service Branch (SSB) of the Mumbai Police supposedly conducts raids and rescues minors from trafficking and AIDS risks. However, the data clearly shows that in hundreds of raids and many arrests conducted over 6 years, no brothels were closed and no minors were rescued, which goes opposite to the popular narrative.

A police officer terms the females in sex work as ‘victim girls’ and ‘criminal men’ who put them to work. A female anti-trafficking court judge also takes up a similar stance, giving them two options – either to be sent back to their native village to their husbands or fathers; or to be sent to a correctional ‘remand home’ to be reskilled under the state.

The patriarchal and patronising tones all around them are visible and give the impression of the ‘infantilisation’ of sex workers as non-citizens incapable of defending or deciding for themselves. Even though 62% of the women were found to be the sole bread earners of their families, they were pushed back to their precarity without consideration for their situations or supporting their causes.

The result is that many of these ‘rescued women’ end up coming back to the same places they were taken away from. Many people interviewed by Bhattacharjya speak of stories of violent families or husbands from whom the women ran away in the first place.

Many also speak of families or husbands themselves as sellers, which shows the lack of voice the women have compounded by a patronising state. Parallel to this is also a conspicuous absence of politicians from visiting the area, while they are also accused of siding with the real estate sharks to claim and shut down many areas to gentrify them and turn them into small factories or industrial hubs.

Race, Class and Caste – intersectional exclusions

A look at the history of the sex work geographies also illuminates a racial and caste-class divide facing the women who enter it. Kamathipura even has racially and regionally segregated alleys – named like ‘Safed Gully’ (White Alley) for women coming in from Europe, or areas demarcated for women from Nepal, Andhra Pradesh, or other regional or racial groups.

Even in raid and rescue missions, women from West Bengal and Bangladesh were treated with criminalising prisms and their testimonies as to their areas of birth, or reasons for joining the sex work industry were completely ignored. Women from West Bengal were even segregated from other Indian women to first check if they truly were Indian.

Also Read: India: NCRB’s Report On Rising Numbers Of Missing Women Is Disturbing

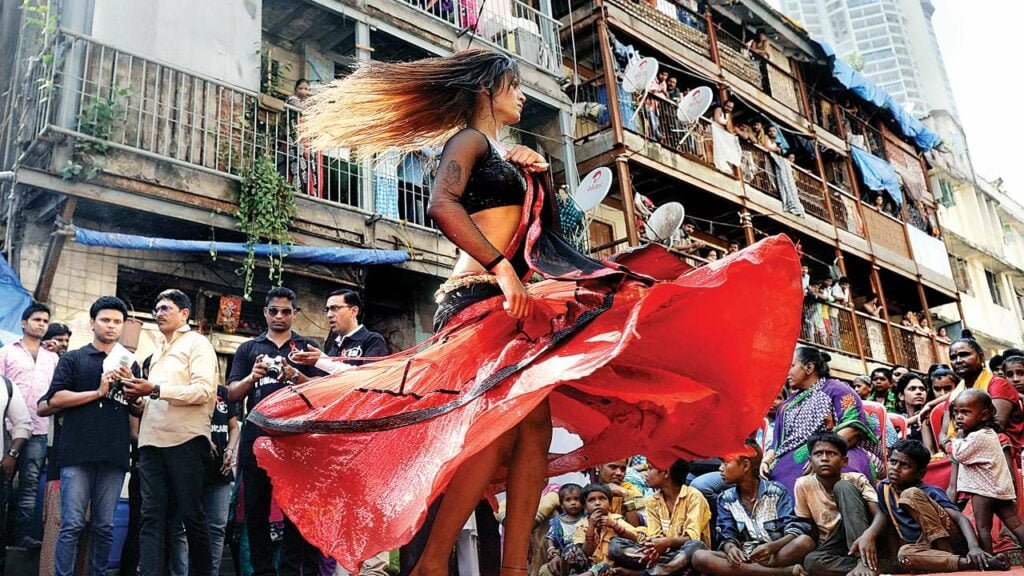

Another dimension of exclusion was that of narrative and access. ‘Prostitution’ was marked as an occupation of the ‘lower castes’, with derogatory terms like ‘Ughdya Mandichi Jaat’ (A caste with open thighs) used to refer to communities of Lavani dancers of Maharashtra as nothing more than sexual deviants. A whole culture of art and performance was thus subjugated to ‘low art’, used to create access to low-caste female bodies for upper-caste men, according to Bhattacharjya.

With the dawn of the neo-liberal economy, a new class of ‘clients’ appeared in the city – migrant labourers of North India who missed their families and intimate spaces. To fulfil their needs, communities like the ‘Bedia’ of Uttar Pradesh (a traditional performing arts tribe), or the performers of Do Arthiya Geet (Double Entendre Singing) of Bihar, were forced into sex work through highly sexualised song and dance for large crowds of men in the city’s suburbs. The reduction of art forms and performances to crude sex work was documented in many studies. Another caste dimension was the reference to this musical tradition as ‘Dhobiya Geet’ (Tailor caste music).

Then comes class. All internet-based agencies advertise ‘decent, well-groomed escorts’ from ‘good families’, only working in five-star hotels. Hobbies like swimming and English education are paraded as desirable qualities. Even the money made by such escorts is significantly higher than ‘cheap prostitutes’, in the words of a respondent.

Also Read: Nalini Jameela: The Author, Sex Worker & Activist On A Mission

The use of condoms and respect for one’s agency in the room is also commonplace in high-end sex work. Those without a high class/caste background, without English speaking abilities, are thus excluded even from such spaces of earning.

The heteronormative and coercive manufacture of consent

Bhattacharjya has thus complicated the notions of binary buyer-seller, purely sexual work, and violence-trafficking narratives by introducing us to skilled cultures, caste connotations, migrant labourers and women as breadwinners in this industry. She then picks up the gap between the studies on the internet and the middle class as consumers or providers of sex work.

She traces websites, ‘models’, casual encounter ‘cruisers’, professionals and ‘massage boys’ who form the stakeholders in the fast-growing internet sexual space. There are narratives of ‘professional escort agencies for the hardworking gentleman’. They claim to provide ‘high-end girls from good families’ for a night of fun, interaction and recreation. But that’s never all, women are advertised with their hobbies, interests, and even the sports they play.

However, the image of the ‘gentleman’ is tempered warnings to not behave ‘rudely’, not ‘haggle for pennies’, and never force the girl to do what she doesn’t like, showing the danger of non-consensual sex as ever present even in this ‘high-end service’.

Another service that Bhattacharjya speaks of is ‘massage boys’ who entertain female clients. However, an element of surprise here is the absence of any payment or even gifts in the ‘exchange’. There are regular clients, some who don’t even have sex but use the interactions as a getaway from oppressive and uncaring husbands to have some semblance of fun.

However, even on blogging sites and online communities discussing sexual interactions, there is a conspicuous absence of women. Bhattacharjya calls such communities ‘safe boys clubs’, that act as non-judgemental spaces for exploration and therapy by ‘co-cruisers’. In conversations with men, both cruisers and massage boys, Bhattacharjya finds a constant assertion of the sexual experience being driven by ‘consent’ for them.

However, this notion is turned on its head by all the female escorts Bhattacharjya interacts with. They claim that not all women entering this space have some precarious circumstance or loan chasing them. Even the notion of a commonly safe industry is denied when workers claim that more than the police, they fear and experience violence at the hands of male clients.

This occurs to the extent that forced sexual acts and even rape is seen as a regular and common ‘occupational hazard’. Thus, the image of independence, agency and consent all seem to fall through the gendered and manufactured space that is internet sexual commerce as well.

Resistance and reclaim – an inclusive idea of sex work as gig work and care narrative

After problematising the discourse that constrains sex works to the objective lenses of violence, sex-based, exploitative, single-gendered, or even payment-driven, Bhattacharjya asks the question about how the conceptualisation of sex work can proceed in India in an internet-driven future. Here, her own analysis of sex work as a part of an invisible and undervalued ‘care economy’, or in her words ‘sex as housewifery’, puts an important context and prism of viewing sex work as beyond a purely economic, or transactional or even a leisure activity.

Sex work is unacknowledged care work, as even its dynamics of consent are as murky as the care work done by a housewife, seen as consenting to do all labour of the household simply due to her consent to the act of marriage. Similarly, a sex worker is deemed to be liable to do anything in a room simply by the fact of them having ‘agreed’ to join the industry. Whoever is paying for the service, man or woman, is seen to hold disproportionate power in the interaction, without a recourse to register grievances.

The internet, though liberating of the exploitation of the ‘brothel owner’, is a complicated space; as sex workers haven’t been able to receive copyrights and payment on their online content by virtue of the morality-based laws that are used to govern all aspects of their work.

These gaps in policy and support, legal and protective, must come by recognition of sex work as part of the unrecognised care economy according to Bhattacharjya. A nod to Bhattacharjya’s conception of sex work was given by the Indian Supreme Court in its judgement recognising sex work as a profession and a right of any Indian citizen under Article 21 of the Indian constitution. This can be moved one step further by adding sex workers to gig workers in the NITI Aayog’s plan for social inclusion, social security and financial access to gig and platform workers in the country.

Documenting sex workers unions and collectives Bhattacharjya sheds light on their fight to show how they are also full-time employees in other jobs in many cases, only moonlighting as sex workers. The recognition and social protection of their work help to bring security to their daily life.

This can also help sex workers to continue practising the other ‘jobs’ that they have, for example, as MNC workers, bankers, fashion industry workers, etc with social and physical security in their sex work simultaneously. It can also help bring women’s voices to the mainstream and remove the stigma and repulsion attached to female sexuality in the public sphere. It may even help reduce underground and illegal activities that go on due to the illegal nature attached to sex work, as recommended by Bhattacharjya.