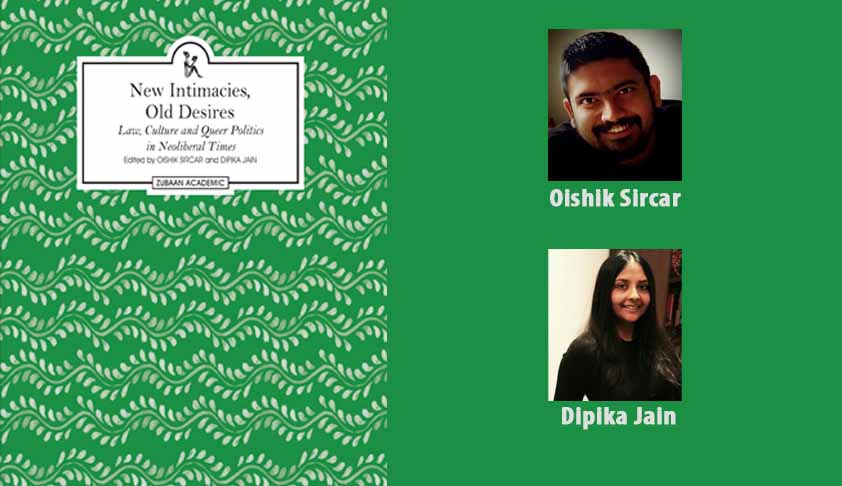

New Intimacies, Old Desires: Law, Culture and Queer Politics in Neoliberal Times written by Oishik Sircar and Dipika Jain, traces how the past decade of law can be cited as ‘the decade of sex rights.’ It presents a tussle between the law and the culture in a neoliberal background when the law that grounds our desires is evolving. At the same time, there are new intimacies, new identities and new forms of connections which also demand the legibility of the law or they demand to get rid of the law and remove its surveillance within our private lives.

Perhaps, the greater challenge in India is to get rid of the peculiar way where welfare laws are made to further marginalise minorities through bureaucratic paperwork, usually in the quest for legible recognition of their identity. Within a political climate run by Hindutva, there also lies the danger of assimilation of justice and rights based framework of queer rights within a largely Hindu dominated narrative which emphasis on the presence in mythology and more on parampara than on welfare, rights, and protection from discrimination (echoed through the Uniform Civil Code debate).

In Homonationalism as Assemblage Viral Travels, Affective Sexualities, Jasbir Puar traces the virality of homonationalism and its firm connection with virality. Puar theorises that virality or the resonance of queer experiences across the globe stands at odds with the ‘west and the rest’ perspective.

The chapters in this edited collection build upon a lot of arguments that are prevalent at the moment. When we ask of governing desires, is it limited to the futility of ‘love is love’ or it’s is extended to a better quality of life itself. Judith Butler has argued in their work about the liveability of trans persons, that is, how much life matters? The same has been echoed by activists like Dr. Aqsa when we discuss same-sex marriage rights. Marriage equality is essential but what after the victory of ‘love is love,’ what about employment? anti-discrimination legislation? reservation? and the recognition of diverse forms of families and communities that queer-trans people thrive through?

In Homonationalism as Assemblage Viral Travels, Affective Sexualities, Jasbir Puar traces the virality of homonationalism and its firm connection with virality. Puar theorises that virality or the resonance of queer experiences across the globe stands at odds with the ‘west and the rest’ perspective. Jin Haritaworn in Beyond ‘Hate’ Queer Metonymies of Crime, Pathology and Anti-/Violence asks – “Why do trauma narratives attached to homonormative victims/subjects circulate at such volume and speed, while experiences of racism, poverty or police violence remain unspeakable and unremarkable?” There is emphasis on queer necropolitics and the crucial question of who needs to die so we can live. This is because survival begins with class and race oppression, and then heteronormativity or homonormativity comes into the picture.

Dianne Otto’s chapter Transnational Homo-assemblages Reading ‘Gender’ in Counterterrorism Discourses argues for a transnational understanding of gender to truly queer international law for justice. Josephine Ho cautions third world intellectuals to be wary of presentation of western civilised modernity on a higher ground, displacing other religions and regions as homophobic and morally unethical, which is not the case. Aeyal Gross in Post/Colonial Queer Globalisation and International Human Rights Images of LGBT Rights discusses the need for questioning the understanding of sex and gender, especially within the systems on an international level, within which we operate for welfare of the queer community.

Also read: The Politics Of Mainstreaming Radical Queer Rights

Through The Men of Blanket Boy’s Moon Repugnancy Clauses, Customary Law and Migrant Labour Sex, Neville Hoad takes a look at ordinary life which exists under the radar of the law, asking – who do the law will work for, if it comes to make space for marriage rights for queers? The chapter Slim Disease and the Science of Silence The Erasure of Same-Sex Sexuality in ‘African AIDS’ Discourse, 1983–88 by Marc Epprecht is a pertinent cautionary tale about the cultural bias that exists in clinical science and literature, especially against minorities through a case of erasure of homosexuality within the HIV/AIDS discourse in Africa.

In Baring and Veiling: Sex, Politics and National Identity in Canadian Legal Discourse, Carolina S. Ruiz Austria brings up the question of women’s bodies being actively pushed as sites to be regulated by the law using the instance of Canadian Multiculturalism and presence of burqa or niqab wearing women. In the concluding chapter titled Queer, beyond Queer, Nishant Upadhyay and Paulo Ravecca argue for queer assemblages and engagements in hope to critically deconstruct power or forms of powers.

Few more chapters are case studies like Selfhood and Archipelago in Indonesia A Case for Human Polyversality by Vanja Hamzić, The Remote Control of the ‘I’ We Assume Wants to Come Out Sexuality and Governance in the Arab World by Sami Zeidan, and In the Shadow of the Homoglobal Queer Cosmopolitanism in Tsai Ming-liang’s I Don’t Want to Sleep Alone by Ani Maitra. Queer Anti-sociality and Disability Unbecoming An Ableist Relations Project? by Fiona Kumari Campbell is an important look at how antisociality can be seen as a possibility of disability analysis and lifestyle. Through rejection of the inclusion agenda (also a core component of Diversity and Inclusion schemes for queer people in corporations, which is mostly tokenism), there is rejection of complicity in the system that oppresses marginalised people in the first place.

Perhaps the most interesting chapter of the edited volume is Polymorphous Reproductivity and the Critique of Futurity: Towards a Queer Legal Analytic for Fertility Law by Stu Marvel. India is no stranger to closing its legal ways to queer community for having a family as defined per the law or as understood in the wider society. It traces the queer desire to form family and how the reproductive aspect is controlled through heteronormative norms. It further looks at polymorphous reproductivity and traces what new intimacies can be formed and discovered in the process.

Also read: ‘Whitney Houston: I Wanna Dance With Somebody’: A Rocky Dive Into The Life Of Queer Icon Whitney Houston

In Baring and Veiling: Sex, Politics and National Identity in Canadian Legal Discourse, Carolina S. Ruiz Austria brings up the question of women’s bodies being actively pushed as sites to be regulated by the law using the instance of Canadian Multiculturalism and presence of burqa or niqab wearing women. In the concluding chapter titled Queer, beyond Queer, Nishant Upadhyay and Paulo Ravecca argue for queer assemblages and engagements in hope to critically deconstruct power or forms of powers. The pathway for the same is through convergence of Marxist, feminist postcolonial, queer, and indigenous perspectives. But this is easier said than done as each of the ideologies brings forth important points to consider if we are talking of a future embedded in true emancipation.

Even if we take the instance of the United States, marriage equality didn’t lead to emancipation as a record number of trans persons died in the pandemic years and a record number were murdered. Moreover, many NGOs saw their funding massively reduced after the right to marry for same-sex couples as most funders thought that’s the last battle to be fought. Erstwhile UK is blocking Scotland’s law to identify one’s own gender, some states in the United States have pushed for anti-trans laws, and former US President Donald Trump has a more draconian future for transgender rights in the US for his election run for 2024. This is a testament that same-sex marriage rights aren’t the end battle for emancipation of all queer people.

At the same time, there’s a lot at stake for marriage equality in India (along with a historic but privilege ridden moment for the first gay High Court judge), Singapore decriminalised gay sex (but blocked marriage equality), and Cuba ratified the historic and landmark The Cuba Family Code 2022 (at present, the most progressive family code in the world), all of which are welcome and positive changes. But they are also in a time and space where critical look is required. In India, the push for same-sex marriage has been critiqued as a savarna project that will mostly benefit cisgender gays and lesbians from the oppressor caste and upper echelons of the society. Henceforth, it would not amount to material benefit for the wider queer community in India. Another crucial instance is of the FIFA world cup where the host country Qatar has been notorious for being queerphobic and similar treatment was meted out to many queer fans who wished to attend the game.

New Intimacies, Old Desires is a worthy critique of global queer politics, and perhaps offers a more nuanced space to think around the context in which the queer community envision the future of queer politics in India. At a time when Bangalore couldn’t hold the pride march, Delhi pride march allegedly saw people raising questions at the slogan of ‘Jai Bhim,’ and Mumbai hosting the worst ever pride march (read: morally sanctioned, depoliticised, and tokenistic) in the history of mankind, we need to shift the focus of queer politics vis-a-vis our welfare rights.

While the edited collection raises crucial questions at the competency of capitalism and how it’s antithetical to queer politics, it offers little to no respite situated within the radical nature of queer politics which has shaped the discourse of queer rights throughout history – from the Gay Liberation Front Manifesto to the intersectional nature of the trans rights movement today.