To look at government statistics is always a bit of a heart-stopping exercise. Most statistics, when looked deeper, are always difficult and scary to behold, revealing facts about the nation that most of us are simply not ready to accept just yet. Furthermore, post-pandemic economic breakdowns have made every aspect of human suffering and inequality in the country a little more difficult, a little more solemn. The 2020-2021 All India Survey on Higher Education (AISHE) Final Report that was released on 29th January 2023 reveals a lot about the current state of Indian education.

Dalit students at prestigious higher education institutes, including IITs, face significant discrimination, and even are given lower test scores compared to their peers. Dalit enrollment falls below the mandated 15% reservation, which is enforced unevenly across different universities in the country.

Yet, on the surface, the study is mostly bearable. Its statistics, at least up front, do not indicate a dire view of post-secondary education in the country. In fact, many of the phenomena observed in the paper are positive in nature. Overall enrolment for students went up by 7.4%, even during the pandemic times, which is even more than the increase between the studies in 2018-2019, which was a mere 3%. The proportion of students from SC, ST, and OBC classes also grew, with a rising trend escalating over the years of the study. The highest ever increase in women in university has been recorded this year, comparing statistics of gross enrolment ratio.

Fields

Gender parity in male-dominated fields is at risk. While fields such as the arts or even commerce may have reached an almost equal standing in enrollment for men and women, this is absolutely not the case in technology majors, including engineering majors. Women still form only about 30% of the field, and the number is still decreasing.

One explanation for this rapidly decreasing trend is the COVID-19 pandemic, which together with lives, took away hopes of higher education for thousands of women. In the face of economic adversity, families absolutely prioritise the education of men over that of women, leading to these women having to give up their studies. Another phenomenon is that women face the brunt of domestic labour in a situation where daycare centres and domestic help is not available, leading to their dropping out of higher education.

Another distinct issue in the report lies in the percentage of students from the SC, ST categories. These numbers lie largely below those from all over India. The GER for all students is about 27.3, while that for those in the SC and ST categories are 23.1 and 18.9 respectively. According to the gender parity index data, there are more men than women in higher education for all categories.

Yet, the worst statistic in the field of science and technology for women is not the number of graduates, but the number of women who enter the workforce in this field. While statistics show that 43% of Indian women graduate with science or technology degrees, only 14% of them enter the workplace, creating a highly skewed workplace environment. This discrepancy can also be chalked up to hiring and promotion discrimination, where women are, consciously or subconsciously, disproportionately selected against during the hiring process. While higher education and its impacts are definitely important, it is what women make of their lives after they are educated that truly matters in their well-being and standard of living.

The underprivileged

Another distinct issue in the report lies in the percentage of students from the SC, ST categories. These numbers lie largely below those from all over India. The GER for all students is about 27.3, while that for those in the SC and ST categories are 23.1 and 18.9 respectively. According to the gender parity index data, there are more men than women in higher education for all categories.

The reasons for this, as expected, lie in discrimination and a class-based hegemony that systematically excludes lower-caste students from reaching tertiary education. Dalit students at prestigious higher education institutes, including IITs, face significant discrimination, and even are given lower test scores compared to their peers. Dalit enrollment falls below the mandated 15% reservation, which is enforced unevenly across different universities in the country.

Also read: Gender In Academia: Women In Higher Education Must Be Retained And Transformed Into Workforce

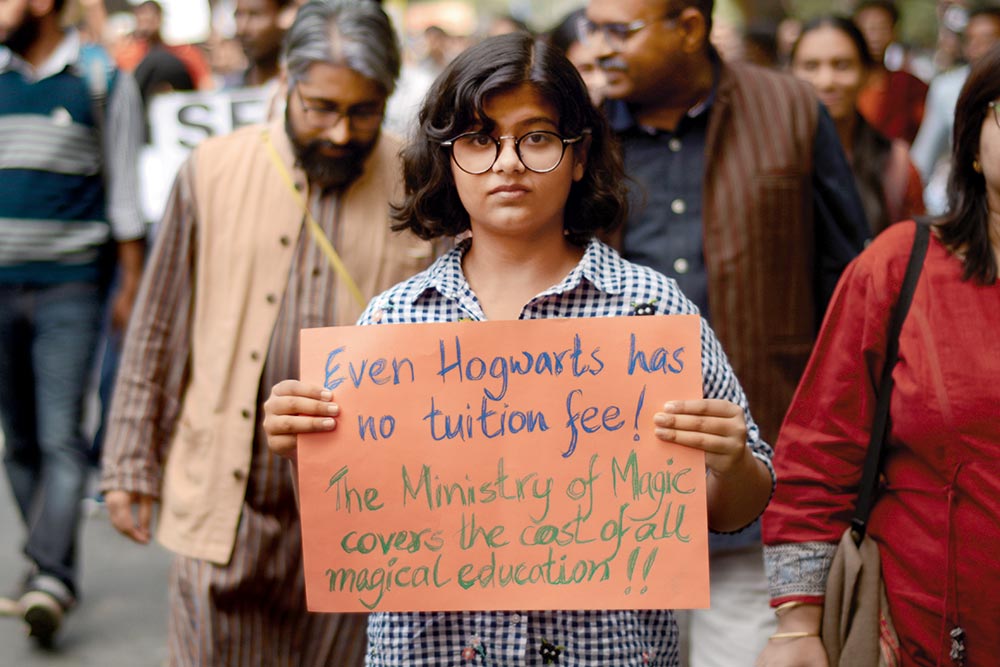

Accessibility and affordability of higher education is another key factor in the low enrollment of SC/ST students in higher education. The privatisation of higher education, especially at the expense of public education, ensures a total decimation of the SC/ST population in higher education. Private universities do not need to conform to reservation legislation, and cost significantly higher, both institutional barriers ensuring their education.

Teachers

Yet, there are still some depressing statistics. One of these is the ratio of teachers to pupils, which remains devastatingly low year after year. The statistics for teachers, for example, is particularly gruesome, with there being only 75 female teachers for 100 male teachers recorded. There is also a particularly high student to teacher ratio, with 24 students to a teacher reported in the AISHE report. The IIT’s, India’s premier educational institution and perhaps the most revered institutions in the country, all face professor shortages of between 15 and 60 percent.

The reasons for this low number, while not detailed in the AISHE report, lie in several infrastructural errors which plague the education industry as a whole. The first issue to consider is a lack of trained, qualified professors in general. It is the state of academia that is at fault here – the field has gained a poor reputation due to corruption, nepotism, poor funding, and political influence. The second issue to consider is that when there is trained faculty available, universities are simply unable to hire them due to a lack of infrastructure.

Also read: Caste-Based Discrimination Rampant In Higher Educational Institutions, Affirms Study

It is simply impossible for universities to hire when their classrooms, staff rooms, and laboratories are simply not big enough to accommodate them. Also adding the complications of state-run universities being unable to hire full-time faculty due to funding cuts, it is simply not feasible for teaching positions to be filled in the higher education field. Coupled with the retiring of current senior professors, it can be assumed that the field will face a significant drain in expertise in the near future.

Looking forward

All evaluations of the AISHE report are highly credible. Yet, some sources have found discrepancies in its pages, disputing the results cited. A report on 7th Feb, 2023 by The Hindu finds “significant inconsistencies” in population projections as well as gross enrollment ratio data.

The AISHE report uses population predictions which heavily differ from census predictions, meaning that their calculations of the GER could differ greatly from the calculations done from census data. Even more shockingly, The Hindu found discrepancies in results when calculating the GER even when using the report’s own predictions, a simple mathematical error.

These discrepancies mostly arise from the prediction of population data. Given that the census is only taken once every ten years, the report relies on projections of population data in order to draw and interpret its data. The 2020 report revised figures from the last four years using 2011 census data, instead of 2001 census data as previously used. This means that several of the data points over the past few years were pushed downwards. Tamil Nadu, for example, which had been lauded for reaching a Gender Enrollment Ratio of 50 in 2019, had a GER of only 49 in 2019 and 46 in 2020 with the new data, hence forcing us to re-evaluate our lens of the past.

Secondly, there are reportedly errors in the data even disregarding the census data. The AISHE report uses population predictions which heavily differ from census predictions, meaning that their calculations of the GER could differ greatly from the calculations done from census data. Even more shockingly, The Hindu found discrepancies in results when calculating the GER even when using the report’s own predictions, a simple mathematical error.

Also read: Towards A Post-COVID India: How Can We Prioritise Adolescents?

It is not certain what the causes of these discrepancies are, or if they have been revised. However, it is noteworthy that the data from this report may differ from reality.

Solutions to the gaps in higher education in the country are difficult to conceive of and conceptualise, mostly due to the complexity of issues and the inertia of the public and the government for welfare and education spending. Scholarships and bursaries for students in higher education from underprivileged backgrounds is one significant step towards helping these students reach their goals. In the long run, investment into educational infrastructure for public universities in particular would go a long way in changing the state of higher education for good.