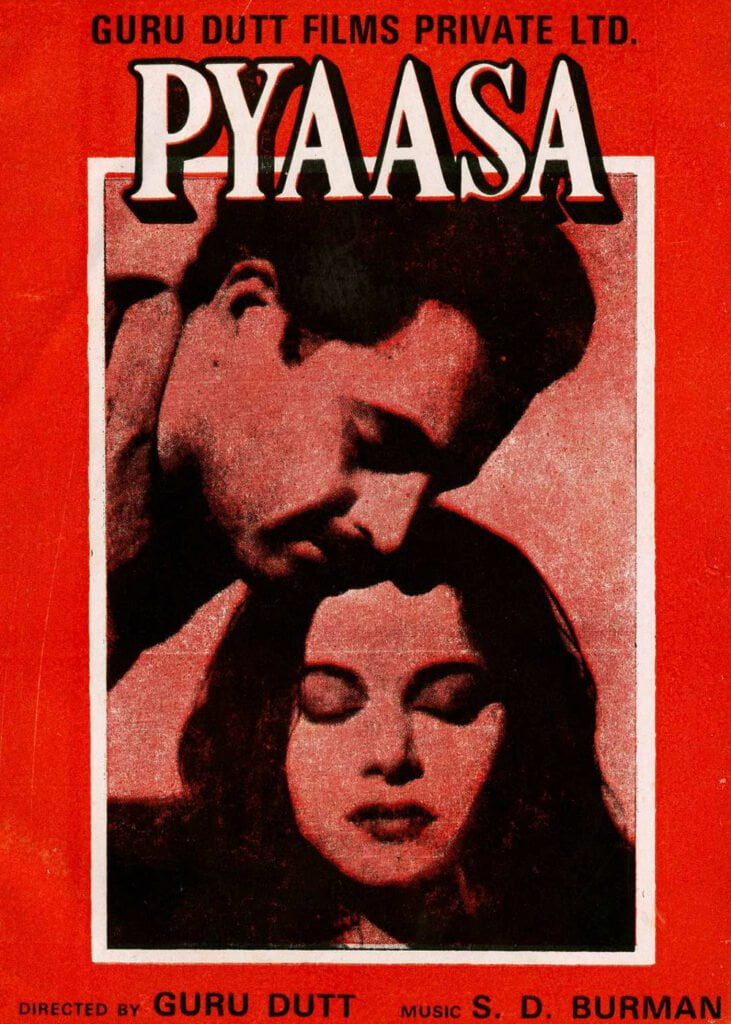

On the first watch, Pyaasa is all about Guru Dutt. Based on his own adolescence as a struggling artist and starring Dutt himself, this is a story about greed, wealth, and the artist archetype. And even on that level, it must be acknowledged that Pyaasa is excellent. Rivalling Dead Poets Society in its ability to convince the watcher to pursue a life of aesthetics and arts, Pyaasa is a story about romance and romanticism of the human experience at its core. But art and capitalism are not all it is about.

Pyaasa is not just a progressive film, it is a decidedly feminist film given its context. In Pyaasa, anti-capitalism is not a sentiment only accessible to men. The filmmakers choose to explore the effects of a materialistic world on all three main characters: the protagonist Vijay, the sex worker Gulabo (Waheeda Rehman), and the ex-lover Meena (Mala Sinha). For this level of character depth to be given to female characters would be remarkable even in today’s times, so it is all the more exceptional that it is a running theme in a 50’s flick.

The Good

Who is a sex worker? For the modern filmgoer, the answer is easy. For many masala films, she is a mere excuse for a dance number. A plunging neckline and knee-length skirt accompany sultry dance moves as drunk antagonists throw money at her. Even critically acclaimed films such as Rajkumar Rao’s Stree have fallen for this trope, an artistically insincere way to invite more of India’s sexually repressed young men to the screens.

Perhaps you would point to Madhuri Dixit’s Chandramukhi as a subversion of the trope. A woman with a heart of gold, always dressed to the nines, never there for the money. This is not an exception to the trope, but another trope in itself – the jilted lover. Bollywood’s redeemed sex workers are done dirty in their narrative. Chandramukhi, no matter which film she is in, will never get her Devdas. She is condemned to pine because no male protagonist has chosen to buck societal trends and forget her perceived impurity for her love.

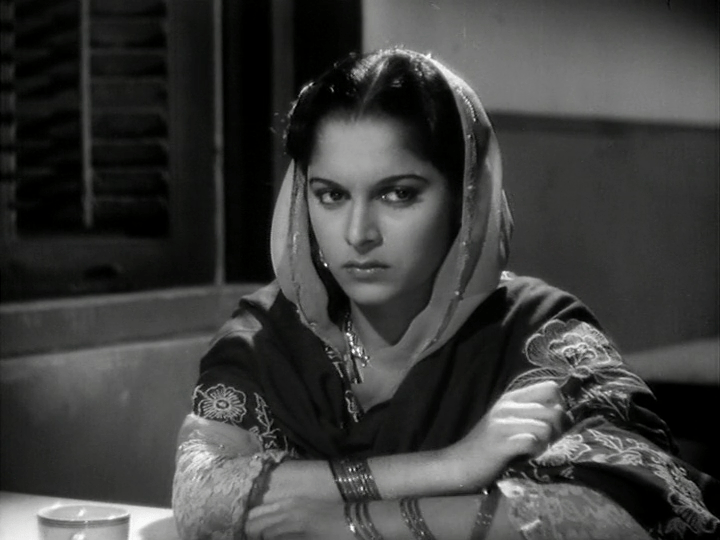

Guru Dutt’s Pyaasa managed to avoid both these tropes, even back in 1957. Waheeda Rehman’s portrayal of Gulabo is never sexualised to any degree, nor is it played for pity. Gulabo is intelligent, she is kind, and she has self-respect like any other woman. The camera refuses to pigeonhole her into a corner by claiming she is chaste, nor does it caricature her as an unfeeling tradeswoman. Instead, her work is simply one aspect of her life, borne out of the poor economy and rampant unemployment. There is no moment where Dutt, through the character of Vijay, demeans her profession, or layers any accusations of impurity on her.

It would be unfair to classify Pyaasa as a feminist classic if the film only looked at its lead with empathy while villainising the rest. But that is not true of the film. Mohammed Rafi’s Jinhe Naaz Hai Hind Par, with lyrics by Sahir Ludhianvi, plays as Vijay wanders the streets of a red-light district. Instead of the camera sexualising these women whose jobs revolve around their sexuality, the camera is empathetic, depicting their illness, their grief, and their desperation. The lyrics, too, are accusatory to the powers that be for overlooking these parts of the population. In another scene, a worker dances in tears, prodded by a strict madam and encouraged by drunken Johns while her child cries of illness.

What is perhaps most surprising is that the film’s hero, Vijay, is no hero in the typical sense. The film acknowledges that these are issues way out of the individual’s control, and there is no singular person who could change the world. Vijay does not rescue Gulabo from her trade, nor does he beat up a couple of moustache-twirling, cigarette-smoking Johns and pimps like a modern Bollywood protagonist might have done.

Instead, his superpower is his empathy, and his ability to extend love to society’s discarded. Gulabo and Vijay are no Devdas and Chandramukhi – Vijay unapologetically chooses a life with Gulabo, with no concern for any societal norms. ‘Jala do ye duniya‘, sings Mohammed Rafi as Vijay walks away with Gulabo in the last shot. Vijay’s rejection of social norms is quiet, but his victory over evil and renunciation of the world is perhaps more impactful than that of any swash-buckling hero in Indian cinema.

The Bad

The Paro to Vijay’s Devdas in Pyaasa is Meena Ghosh, Vijay’s childhood flame. The two are seen to fall in love in their school days but drift apart for unknown reasons. In the present, Vijay realises she is married to Mr Ghosh, his boss and publisher. She admits that she loves him, but married him since he can provide economic stability.

Meena and Gulabo are foils to each other. One is born into privilege, and the other has nothing, to begin with. Gulabo chooses her love over money, while Meena chooses her economic interests over love. Dutt portrays this as another symptom of the corrupt, materialistic world, a world which suppresses human emotion in exchange for wealth and prestige. She is viewed not as poorly as the villainous Mr Ghosh, but still as greedy and morally corrupt.

Yet, it is not a far reach to do a feminist reading of Meena Ghosh. Meena Ghosh, for once, is not a villainous character. She feels anguish over her actions. She is still very much in love with her ex-boyfriend, and to some degree regrets the decisions she made in greed. Meena has faced the consequences of giving up her morals and values for the economy and sees the folly of her ways.

Meena’s choice in the film also depicts the patriarchal bargain. What choices do women have in a capitalist, yet patriarchal society? When power lies in the rich, but only men have the chance to participate in the economy and earn a living, the choices lie between being Gulabo – sexually exploited, working in a trade that no one willingly enters, and being Meena – marrying an abusive man for a shred of stability in life.

The filmmaker swerves the Madonna-Whore comparison and gives both Meena and Gulabo similar compassion and empathy despite their choices. Yet, his sympathies lie solely with Gulabo, refusing to acknowledge the intricacies of love and marriage in a patriarchal society. Dutt does genuinely believe that Gulabo’s choice to earn money through prostitution is justifiable because of the economic conditions of the country, but does not offer the same moral wriggle room to Meena.

While the filmmaker’s layered characters are commendable, his viewpoint on morality and decision-making in patriarchy needs to be re-examined with what we know about gender and gendered restrictions today.

The Ugly

Pyaasa, a film often so depressing it needs its dance numbers to give its audience any relief, remarkably excels at its comic relief characters. Johnny Walker’s Abdul Sattar provides levity during some of the more tense moments of the film. The song he performs, ‘Sar Jo Tera Chakraye‘, is instantly recognisable across Indian households, and Walker’s skill as an actor does not go unnoticed. His character, even with limited screen time, shines, an impressive feat for essentially a tragic film.

Yet, the beautifully complex film is scarred with a cheap attempt at humour in the form of Pushplata (Tun Tun), Vijay’s classmate. A visibly fat character, Dutt sticks to tried and tested fatphobia as a means of generating humour in the film. For a film that can humanise a singing masseuse and a poetry-reciting sex worker, it leaves a bitter taste in the mouth to notice that it cannot do the same for its female characters who do not fit into conventional beauty standards. Tun Tun’s calibre as a comedienne – she was known as Hindi cinema’s first-ever comedienne – is forgotten in favour of making jokes about her weight.

What remains now

Among younger audiences and the casual film-goer, Pyaasa is barely remembered. Among cinephiles as well as international audiences, Pyaasa has received recognition as one of the finest films of not just the era, but of the industry. Recently, it was given a well-deserved spot on Time Magazine’s All-Time 100 Movies list, an acknowledgement of its stellar storytelling and universal themes. In a film where women could have been incidental to the plot of a struggling artist, Guru Dutt has incorporated the stories of three-dimensional, fleshed-out women with empathy and a modern outlook unlike any other.

For the frustrated artist, the tired worker, and the feminist, Pyaasa is soul food. You’ll never look at the world the same again.

Agree with the review in general but just wanted to add my 2 cents – I first watched the film when I was in my late teens, going through my own existential angst, questioning the meaning of life, etc. etc. and trying to make sense of an absurd world. Even then, I thought the movie was essentially a self-indulgent depiction of a frustrated wannabe poet, who proudly exhibited his tormented persona as an art form, though it was (to me) clearly a manifestation of self-pity. The characterization of women to me seemed too stereotypical and barely rose above caricatures, saved only by the acting prowess of Waheeda Rahman and Mala Sinha. Couldn’t agree more re: your notes about fatphobia and comedic tropes around it. Loved the songs by Sahir, but that’s about it.