By Sahana Sitaraman

One fine day, around 12-18 months after a baby is born, parents get to experience the utmost joy of hearing their child’s first word. Mahita Jarjapu’s parents had to wait longer than usual to hear their daughter speak, all the while anxious if she would ever be able to.

In the dreary month of February 1990, Mahita’s parents were told by doctors that their 19-month-old daughter had profound bilateral sensorineural hearing loss – a condition in which the vibration-sensing hair cells in the ear are damaged.

“It is disappointing to see that three decades later, parents are still not advised about auditory-verbal therapy, which is much more comprehensive than speech therapy for developing speech-language skills in young children with hearing loss“

Prasada Rao, Mahita’s father

They were told that without specialised hearing aids or a cochlear implant surgery — a fairly new and experimental technique in 1990 — Mahita will not be able to hear anything.

Desperate to hear Mahita talk, they took her to multiple doctors, audiologists and speech therapists, but were disappointed to see how children with difficulties in the hearing were nowhere close to speaking fluently.

One day, a neighbour came dashing into the house and told them about Dr S R Chandrasekhar Institute of Speech and Hearing in Bengaluru. They travelled from Hyderabad to visit the institute and were redirected to Balavidyalaya – The School for Young Deaf Children, in Chennai, Tamil Nadu. That marked the turning point in Mahita’s journey.

Together we thrive

At that time, Balavidyalaya was one of the very few schools in India practising ‘early intervention’ to help develop speech in children with hearing loss. Their method was rooted in making a child wear the hearing aid throughout their waking hours and exposing them to as many verbal stimuli as humanly possible, and as early as possible, to try and forge the auditory-speech pathways during the crucial years of growth.

But it came at the cost of Mahita’s mother tongue Telugu, as the technique worked best if only one language was used to communicate, in a bid to limit confusion. Mahita’s parents chose English, which was not only new to her but also her mother.

Every day, Mahita and her mother would go to school, learn new words and sentences in English and progress together. At home, from dawn to dusk, Mahita was at the receiving end of a constant running commentary of the most mundane to the most interesting activities of the day.

Around five months after starting at Balavidyalaya, Mahita’s parents finally heard the most precious sound in the whole world. She opened her tiny lips and said amma and nanna.

Also read: Disabled Women And Marginalisation: Are Our Laws Ableist?

Five years went by in a flash and the teachers at Balavidyalaya said Mahita was ready to join a mainstream school. Wishing to be closer to their extended family, Mahita’s family went back to Hyderabad and got her enrolled in Class 2 at Sherwood Public School. The 11 years Mahita spent there were critical in developing her confidence and drive to pursue goals deemed unattainable for her. She knew to take all the support and kindness and pay it forward. Friends remember Mahita as a bundle of positivity and kindness. “I always talk more about what I got from her than what I was able to do for her,” her friend Abhimitra Meka said, with a nostalgic smile. From teaching patience and tolerance to inculcating a drive to keep knocking down barriers, Mahita has been a strong influence in all her friends’ lives.

Hearing the inner voice

As the end of school years approached, Mahita found herself gravitating towards the field of medicine. “I was always interested in science and used to read these ‘Did You Know’, ‘Inventions and Discoveries’ types of books right from Class 6,” Mahita recounted.

“Although Mahita’s speech might not be very clear, the way she communicated her research ideas, was probably one of the best ways. That made me wonder, do we sometimes over-emphasise accents, pronunciations and how we speak?”

Dr Nandita Madhavan

But knowing well that the Indian government did not approve of doctors with hearing issues, she chose to pursue basic science. College was a major change. With classrooms accommodating hundreds of students doing parallel conversations and teachers facing the board while speaking, Mahita realised that she was missing out on a lot. She could not lip-read if the speaker was turned away from her.

But she put in extra effort to be on par with her peers, and this drive got her into the Indian Institute of Technology Madras to pursue a master’s in chemistry. Not only did she excel in academics, but she also changed perspectives on communication.

Her thesis advisor Dr Nandita Madhavan said with pride in her eyes, “Although Mahita’s speech might not be very clear, the way she communicated her research ideas, was probably one of the best ways. That made me wonder, do we sometimes over-emphasise accents, pronunciations and how we speak?”

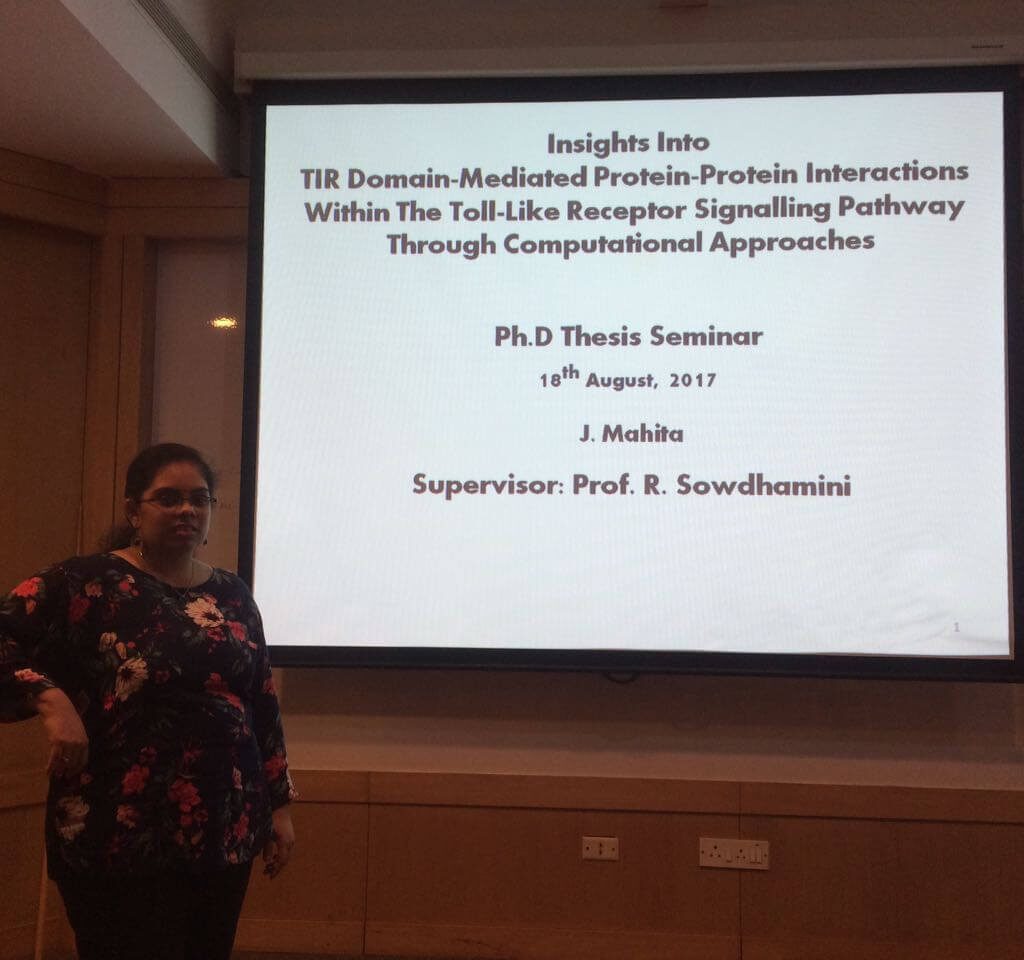

Mahita continued her streak of excellence and joined Prof R Sowdhamini’s group at the National Centre for Biological Science (NCBS) for a PhD, in 2011. In the six years she spent there, she dazzled her advisors and peers with her intelligence, patience and diversity of talents.

Continuing her academic career, Dr Mahita went to Prof Chris-Bailey Kellogg’s lab at Dartmouth College for her first postdoc and is currently in the lab of Prof Bjoern Peters, at La Jolla Institute for Immunology, San Diego, California. She is working towards understanding what makes an antibody choose a particular binding site (or epitope) on the antigen and is also involved with the Coronavirus Immunotherapeutic Consortium.

Her friends and colleagues went the extra mile to make sure she was included in all settings — formal and informal. “I ensured we did not switch to Hindi or other languages, while Mahita was there,” recounted Pritha Ghosh, Mahita’s friend from NCBS.

But her most challenging, yet fun experience with Mahita was when she taught her Odissi. Ghosh reminisced, “Whenever I taught her, she would ask me what is the gap between this step and the next, in seconds? It made me look at dance in a different way.”

“Over time, I have come to realise that her way of thinking is quite valuable. When I replicate that and try to think along the same lines, I tend to be a more satisfied scientist,” said Abhimitra.

Also read: FII Interviews: In Conversation With Kiran Nayak. B, A Trans, Disabled, Award-Winning Social Activist

Being in environments not designed for people with hearing issues challenged Mahita to come up with her own ways of doing things. “Since I already know that during seminars, the audience might not be able to follow my speech/acoustically understand me fully, I make my presentations in such a way that they are self-explanatory while ensuring the audience is not overwhelmed by the amount of text on the slide,” Mahita explained.

Extensive reading of literature made up for the missed conversations in group settings. But sometimes, being oblivious to these exchanges acted as an advantage. “If someone in a group is discussing how difficult a task is, and I miss out on that part of the conversation, I might go ahead and attempt it and try to make it work,” Mahita said.

Excellence as a way of life: Dr Mahita Jarjapu’s story

Continuing her academic career, Dr Mahita went to Prof Chris-Bailey Kellogg’s lab at Dartmouth College for her first postdoc and is currently in the lab of Prof Bjoern Peters, at La Jolla Institute for Immunology, San Diego, California. She is working towards understanding what makes an antibody choose a particular binding site (or epitope) on the antigen and is also involved with the Coronavirus Immunotherapeutic Consortium.

Since moving to the US, and with the start of the Zoom era, Mahita has gained immensely from regular access to closed captioning during meetings and seminars. Having visited and lived in multiple countries, Mahita felt India has much to learn in making spaces more inclusive.

Awareness about early intervention and special education at a young age is a must. But even more crucial is the integration of children with disabilities into mainstream schools, facilitating not only their growth but also the inculcation of acceptance in children without disabilities.

Prasada Rao, her father, feels the country has a long way to go. “It is disappointing to see that three decades later, parents are still not advised about auditory-verbal therapy, which is much more comprehensive than speech therapy for developing speech-language skills in young children with hearing loss,” he said.

Also read: Coming Home To My Disabled Body

“From the beginning, our objective was to make her stand on her own. She should not depend on anybody. We did whatever was needed to achieve that goal,” Rao said with certainty.

Their efforts have borne the sweetest fruits. A journey that started with tears of agony has transformed into one where Mahita’s parents’ eyes swell with tears of pride.

About the author(s)

101Reporters is a pan-India network of grassroots reporters that brings out unheard stories from the hinterland.