By Nita Shashidharan

Going for walks, just looking at the trees along the way, was a favourite pastime of Dr Harini Nagendra in her childhood. “My mother Manjula is a Botany graduate. When we spent our holidays in Salem, her hometown, we visited Yercaud’s botanical garden. When in Bengaluru, we went to Lalbagh and Cubbon Park. In Delhi, I followed the same routine with my father,” reminisced Dr Harini (50), a Professor of Sustainability at Bengaluru-based Azim Premji University, where she serves as director of the Research Centre and the Centre for Climate Change and Sustainability.

“My mother and I would together dissect flowers to study their parts,” Harini says, adding that she realised only much later that all these exposures have subliminally influenced her.

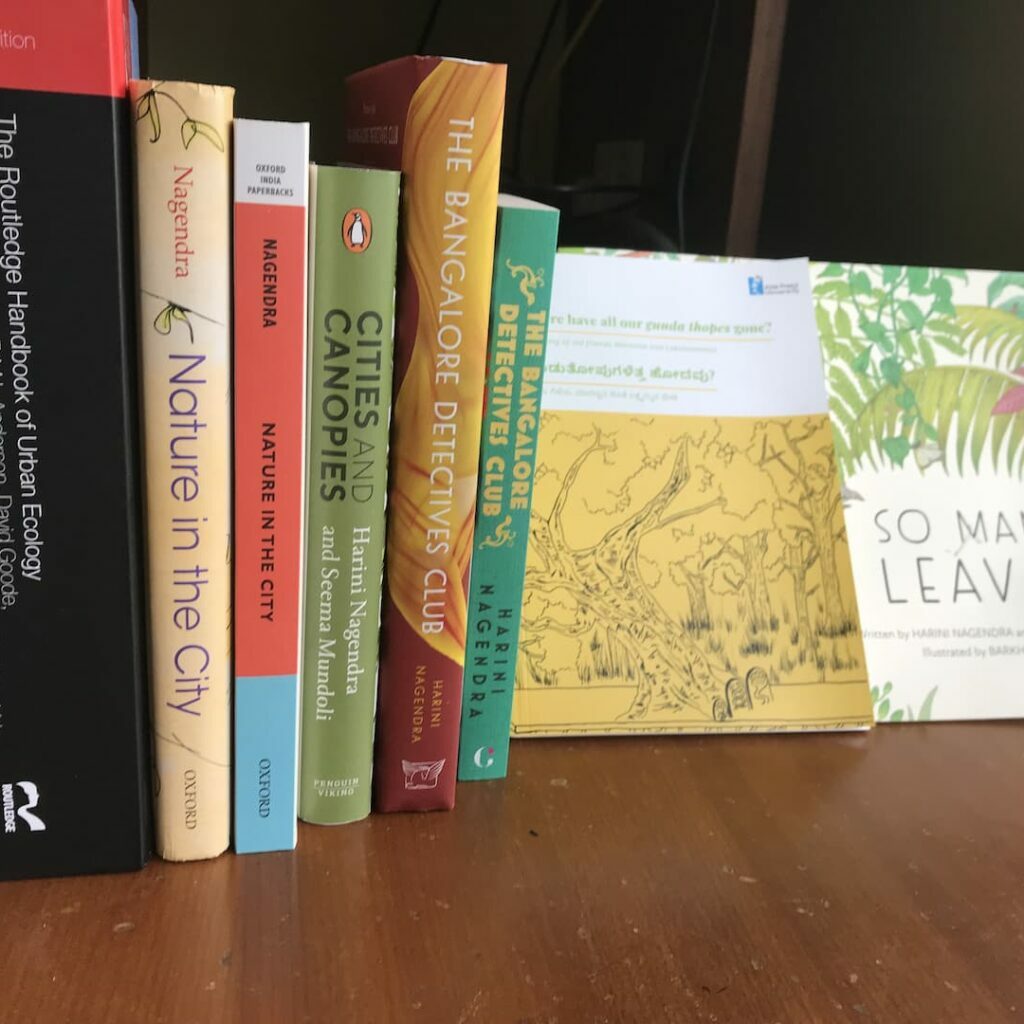

Harini regrets not having chosen BSc Botany. Nonetheless, her engagement with trees continued, with a focus on the changing relationship between people and nature. Her book titled Nature in the City, and those co-authored with her colleague Seema Mundoli — Cities and Canopies, Where have all our Gunda Thopes Gone? and So Many Leaves — are proofs of her passion.

Harini says she is fortunate to have women in her family, who stood as strong pillars of support both before and after her marriage. Her grandmother Thungabai and aunts in Bengaluru and Coimbatore got her more interested in nature as a child.

Her father CV Nagendra always pushed her to reach for the skies, while her husband Venkatachalam Suri and daughter Dhwani inspired and encouraged her constantly. Harini also owes a lot to her housekeeper Lakshmi, who took on so many of the household responsibilities over the past 20 years and gifted Harini the time and mental space to facilitate her work.

Both her mother Manjula and mother-in-law Annapurna had to fight against the traditional family mindset that discouraged women from pursuing education. They completed BSc courses but had to give up on further studies. “My mother-in-law was always extraordinarily thrilled that I could do my PhD. She is glad that I can continue to work on my research and passion.”

Finding her path in research

When Harini joined the Integrated PhD Programme at the Indian Institute of Science (IISc), she was still figuring out her career path in biological sciences.

“I was at the IISc’s Centre for Ecological Sciences (CES) to attend a talk by an evolutionary biologist. But instead, by chance, I heard ecologist Dr Madhav Gadgil speaking, where he stressed the need to do research relevant to humanity, something that links to the problems influencing our daily lives. This echoed with me since I too wanted to do socially relevant research. It is one of the reasons I entered the field of ecology,” she says. In Dr Gadgil, she found her PhD mentor as well.

In the 1990s, Harini was one of the few women ecologists working on remote sensing in India. Using satellites and other remote technology, remote sensing can provide information about the Earth’s surface without coming into direct contact with it.

“It is a technical field. But only quite recently, when participating in a few conference panels, did I realise that we had only a few women in it.”

“Since the 1990s remote sensing has advanced rapidly in capabilities and applications. I started working in this field because I wanted to understand the changes taking place in the entire Western Ghats. To examine changes across a region of that size, you need an ‘eye in the sky’ view from remote sensing satellites. Satellite images have improved significantly in terms of spatial and spectral resolution, enabling us to see landscapes at a much higher level of detail than before. Access to cloud computing and advanced computational approaches now allows us to study landscape change in multiple forests and cities at a speed and quality of analysis that would have been unimaginable 30 years ago,” remarks Harini.

During her PhD, the CES did have women researchers, but women pursuing PhD were fewer in number. Fewer still pursued field research. Harini herself did more remote sensing than fieldwork for her research. She first experienced fieldwork challenges during her site visits and biodiversity surveys.

“It was a time when India had only a tiny pool of ecologists. Priya Davidar, Kaberi Kar Gupta, Aparajita Dutta, Divya Mudappa and a few others were there, working in very difficult environments. In contrast, my Western Ghats work was in settled landscapes. I was always interested in places that have people’s presence, but it was still difficult. Being a single woman in the field, there were safety and travel concerns, besides problems in getting accommodation,” Harini says.

Over time, she moved on to do more socio-ecological and interdisciplinary research in sustainability. This gave her insights as to how local communities were more willing to communicate with a woman researcher than one from the opposite sex, despite them being strangers, and often put forth probing questions.

She thinks certain places are a lot safer for field work, especially when you know the language that people speak there, dress in a culturally sensitive way, and when on sites that are known to be hospitable to everyone. “Some areas are just more accepting of strangers. Generally, if you go off the beaten path into rural Goa or Maharashtra, it is typically safe. I think in many parts of rural India, even if you go alone, you would be safe because there is a community that has its way of treating women with respect. It is in urban centres, where such connections are gone, that safety sometimes becomes an issue.”

Even today, Harini is concerned when her female students go to the field, and always helps them with measures to remain safe.

Bias in academia

Harini does not shy away from calling out bias in academia. In her interview with Vrushal Pendharkar for IndiaBioscience, she can be seen drawing from her experiences and voicing her stance on the structural and systemic barriers for women in sciences.

Dr Shivani Agarwal, her former student, currently pursuing postdoctoral research at Columbia University, remarks, “Being a woman in science, we think we cannot have it all. But look at Dr Harini, she has a career, a family, writes books, takes care of her in-laws and mother, and is financially strong. When I look at her, I think we (women) can have it all.“

On writing beyond research

“Writing is like breathing to me,” Harini says, sharing how she was already writing fiction at the age of seven. She recalls how her English teacher, Mrs Joseph, taught her to think more about nuances in literature and storytelling.

“Dr Raghavendra Gadagkar, a Behavioural Biologist at the IISc, is another early mentor. He introduced me to terrific authors, mostly scientists writing for the public. He invited several of us during our PhD days to write for Resonance, a magazine that aims at popularising science education. I wrote many articles for it. That was a key moment for me,” she notes.

Wanting to bridge the gap between research and outreach, she started writing for the media. “When people write back to me or talk to me about the issues I raised in my writings, it gives me a space to engage with them. I learn. I grow.”

For over nine years, she has collaborated with Seema Mundoli, Assistant Professor, Azim Premji University, to come up with books and research articles. “We share a common goal of wanting to take our research to the wider public. Harini stands out for the way she treats people. She gives me the freedom to write and is very supportive and empathetic to the cause as well as the person. She celebrates differences, instead of making an issue out of it,” says Mundoli.

You get a glimpse of Dr Harini’s feminist side through the character Kaveri she sketched for her mystery novel, The Bangalore Detective Club. Borrowing from her historical research in Bengaluru, she explores themes of colonialism, women empowerment, and independence in this book.

‘A scientist who does not stop at science‘ is a phrase that rings a bell as you flip through her multitude of writings and keep abreast with what she continues to accomplish, by leading research on land change and sustainability issues of forest, lakes, and cities in India and globally. A well-known public speaker, Harini has over 150 scientific publications and multiple national and international awards to her credit. She stands for what many passionate environmental researchers would want to be — someone who makes her voice matter for the causes she believes in.

This piece was originally published by Rukhmabai Initiatives, an endeavour by 101Reporters to make Indian STEM more inclusive.

About the author(s)

101Reporters is a pan-India network of grassroots reporters that brings out unheard stories from the hinterland.