A browse through the ‘alpha male‘ videos on social media will give a glimpse of the meaning behind the title – it will be flooded with comments like ‘women belong in the kitchen‘, ‘men used to hunt, women used to cook‘, portraying the exclusivity and subjection that is associated with the space of the kitchen.

The internalisation of the kitchen and the subsequent negligence regarding the politics around it has now given way to discussions regarding the operation of a patriarchal dogma in these cooking spaces.

Kitchen as a ‘feminine space‘

The limited visibility of kitchens in public spaces has much to do with their conditioning as an exclusively female space. In our scenarios where the kitchen is being presented in the visibility of the public, it is often represented as a masculine entity. The cooking reality shows can be an example, where ‘chefs‘ are traditionally male.

This also draws attention to the dichotomy of domestic and public cooking where women are mainly related to the former rather than the latter. This not only creates a distinction in cooking practices but also leads to the institutionalisation of unpaid labour practised in domestic spaces.

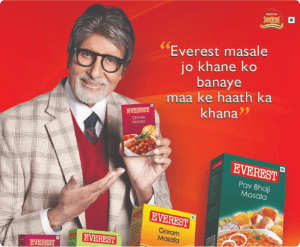

The association of mothers with “good, home-cooked meals” has been a constant narrative where cooking becomes embedded in the patriarchal construction of femininity. This also creates the idea of a ‘good mother‘ who cooks good food for her family.

This romanticisation of cooking as an expression of love and care leads to altruistic attitudes in women thus constructing female ideals of care. The glorification of home-cooked meals often imposes a discriminative standard on women, where they draw their ‘feminine worth‘ from cooking for the family.

Through the exclusivity associated with the kitchen, cooking becomes instituted as the domain of women – their only access and expression of their status in the family. Mothers who devote their entire time to preparing food for their families are glorified and venerated through occasional appreciation and frequent silences. Therefore, the ideal mother figure is stereotyped and romanticised through the imposition of patriarchal expectations of motherhood.

This interrelation between women and their cooking skills directs toward anxiety in connection with cooking skills. The bride acquiring the love and appreciation of her conjugal family through cooking a meal (Pehli Rasoi ceremony) is a recurrent theme in many Hindi soap operas and films. The tension and anxiety that is inflicted upon the women during this ceremony is a manifestation of the desperation women face to be appreciated and how it has created a systematic way in which women become victims of patriarchal ideals.

Also Read: From Veruthe Oru Bharya To The Great Indian Kitchen: Female Identity In The Domestic Space

This anxiety is passed through generations of women thus creating an institutionalised form in which women are subjected to drawing their worthiness through the fulfilment of these ideals thus strengthening the subjugation.

The use of ‘women who cannot cook‘ to represent the trope of ‘bad housewife’ in the media should also be discussed along with this. The humour instigated by showing ‘modern‘ women mistaking sugar and salt was a regular scene in the family dramas where the distinction is shown by using them opposite to the ‘ideal Indian women‘ who can cook the entire thali for the whole family, three times a day.

The Malayalam film named “Njangal Santhushtaranu” (1999) is an example of this where the ‘modern wife‘ is constantly ridiculed by her husband because of her inability to fulfil traditional wifely duties. The filmmaker also highlighted this by contrasting the woman with the husband’s sisters who are conditioned to excel in domestic duties at an early age.

Another example of this can be drawn from the character of Rachel in F.R.I.E.N.D.S and the contrast with that of Monica from the same show. Monica’s association with cooking manifests her highly ‘domesticated‘ nature along with constant shaming of Rachel for her inability to perform household chores.

The exercise of male power in the kitchen

While women are shamed for their inability to cook through popular perceptions, men are considered (as if) genetically unable to perform kitchen chores, further enforcing the femininity of domestic work. When women’s cooking skills are embedded in their femininity, for men it is a means of helping out (which they very well can opt out of without being morally shamed).

This optionality that comes with men’s cooking creates a situation where there is a glorification of the bare minimum. When a man prepares Sunday brunches and tea/coffee for himself, those acts are perceived as signs of his egalitarian practice and gender-equal attitude. The role of internalised patriarchy also performs a role here as women themselves restrict the male members from doing kitchen duties.

Moreover, the leisure attire of men’s cooking contrasts with the obligatory form of women’s cooking where women do not have a choice. This creates a distinction in the perception of cooking when men and women perform it. For men, cooking becomes an exciting hobby or a display of their culinary artistry. Another aspect of culinary masculinity deals with how certain cooking practices are masculinised and treated as male domains due to the ‘roughness‘ of the work.

The notion of cooking food ‘the right way’ has been a significant site in examining the power politics in the domestic cooking sphere. We have often seen women around us cooking according to the taste and likeness of the authoritative male members around them – fathers, brothers, husbands, sons, and sons-in-law.

H. Allen Smith describes this as ‘Hot Pepper Machismo‘ in his book The Great Chili Confrontation where a man projects his hegemony over a specific domain of cooking because none of the other members can handle the heat of cooking (that particular recipe or that particular way of cooking). Thus a recipe becomes a man’s exclusive territory. And, the mansplanation leads to the standardisation of a certain food/taste, forcing women to constantly seek male validation by altering their taste according to the male members of the family.

Also Read: Rasode Mein Kaun Tha? – The Kitchen As A Site Of Contention In Feminist Politics

The notion of cooking food ‘the right way’ has been a significant site in examining the power politics in the domestic cooking sphere. We have often seen women around us cooking according to the taste and likeness of the authoritative male members around them – fathers, brothers, husbands, sons, and sons-in-law.

Here, the taste of the male members is considered to be superior to that of the women in such a way that the women have to amend their practices according to the patriarchs’ palates. Here, the food is subjected to a male taste which the male members validate.

Kitchen as a site of resistance

The early feminist studies’ attempt to relocate itself from the domestic spheres has changed with the third wave of feminism and an analysis of how patriarchy is operated through everyday practices, in both public and domestic spheres. If the kitchen is a feminine space, it may also be a site of resistance.

Neeraj Ghaywan’s short film Juice (2017) depicts the intricacies of patriarchal manufacturing and domestic work by showing a group of women who are working in the kitchen, making food for their husbands during an office reunion. It depicts the kitchen as a politicised space where various issues relating to the oppression of women are being discussed and how domestic work puts women in a vicious cycle of duties and finally the resistance that stems from frustration.

Also Read: Positing Gender Dynamics In The Spatial Discourse In The Great Indian Kitchen

Placing the kitchen in public visibility creates a feminist consciousness that has been normalised through years of patriarchal conditioning.

Similarly, Jeo Baby’s much-discussed film The Great Indian Kitchen (2021) has effectively portrayed the various agents associated with the kitchen that forces women to conform to patriarchal ideologies through the life of a newly married woman in an upper-caste Kerala household. The camera pans through various elements in the kitchen that has been overlooked and concealed – the repetitive chores, the overflowing sink, and the heap of dishes.

Placing the kitchen in public visibility creates a feminist consciousness that has been normalised through years of patriarchal conditioning.

The film exerts a strong feminist gaze on the domestic chores which are often ‘glorified‘ as a female domain. The monotony and repetitiveness of events in the movie scream how life for women has been from the inside. No glorification or romanticization could ever conceal the inherent patriarchy and oppression that makes the ‘female abode‘.

References:

- Adler, T. A. (1981). Making pancakes on Sunday: The male cook in family tradition. Western Folklore, 40(1), 45-54.

- Cairns, K., Johnston, J., & Baumann, S. (2010). Caring about food: Doing gender in the foodie kitchen. Gender & Society, 24(5), 591-615.

- Floyd, J. (2004). Coming out of the kitchen: texts, contexts and debates. cultural geographies, 11(1), 61-73.

- Joseph, N. B. (2002). Introduction: Feeding an Identity-Gender, Food, and Survival. Nashim: A Journal of Jewish Women’s Studies & Gender Issues, 7-13.

About the author(s)

Hajara Najeeb is an Independent Researcher working on issues of Minority Rights and Affairs, Gender, and Politics.