The societal glorification of motherhood often reinforces the idea that women are inherently born as caregivers. Mothering is not seen as a woman’s choice; instead, motherhood is socially constructed as the most desirable life-goal to the extent that she is even raised onto the pedestal of divinity, and perceived as the epitome of sacrifice. This glorification of motherhood is reinforced using cultural symbols, advertisements, and films.

Bollywood’s glorification of motherhood stretches from its synonymisation of motherhood with nationalism in Mother India to depicting a super mother, Sridevi, in Mom, who murders her daughter’s rapists. However, motherhood is only celebrated in the heteronormative upper caste and class backgrounds – for example in movies like Hum Saath Saath Hain and Hum Aapke Hain Koun, pregnancy is treated as a pompous family affair – one that brings the family together and makes it richer. This glorification of pregnancy is profoundly seen in the character of Priya Malhotra in Chori Chori Chupke Chupke, where she persuades Madhubala to have sexual intercourse with her husband to conceive a baby when she realises she cannot carry one herself.

However the portrayal of unwed mothers is often a topic that needs to be analysed. When pregnancy happens outside of the heteronormative settings, how is it treated? Here, we discuss the portrayal of unmarried mothers in Bollywood cinema through three films – Aradhana (1969), Kya Kehna (2000), and Mimi (2021). The protagonists of these movies are women of different times and spaces. Hailed as progressive movies depicting stories of unmarried mothers, we examine whether these movies have significantly changed how stories of motherhood are told in Bollywood cinema.

However the portrayal of unwed mothers is often a topic that needs to be analysed. When pregnancy happens outside of the heteronormative settings, how is it treated?

In Aradhana, we see an educated, liberated modern woman in Vandana Tripathi, travelling through a bus in Darjeeling, getting lovestruck by the charming Air Force pilot Arun Verma. They soon fall in love, “approved” by Vandana’s supportive father and Arun’s superior officer. However, they get married in a temple without their relatives. The fates turn when Arun is killed in a plane crash, leaving Vandana alone, who discovers she is pregnant. However, Arun’s family disapproves of her, calling the marriage a farce. As Vandana moves ahead with her pregnancy, the film portrays how a “good mother” should be, idealising and epitomising Vandana’s two-decade-long “self-sacrifice” for her son.

Kya Kehna revolves around Priya, who gets pregnant with Rahul, who dumps her when she gets pregnant. She leaves her home after a fight ensues with her parents. However, upon their love for their daughter, the family reconciles with her and supports her in her pregnancy. Priya rejoins her college with the support of her parents and her friend Ajay, much to the dismay of others. In the end, Rahul apologises and proposes to Priya after she delivers the baby. However, the movie ends as Priya chooses Ajay over Rahul.

Mimi is the story of Mimi Rathore, who dreams of being a heroine in Bollywood. She ends up becoming the surrogate for a couple from America. However, the couple change their mind after the doctor diagnoses that the child could be born with Down syndrome, abandoning the pregnant Mimi. She disagrees with abortion and delivers the child in her home, saying that the child is hers and Bhanu’s, the driver who brings the US couple to India. After the child is born, Mimi abandons her dream of becoming a heroine to become a “devoted” mother. Toward the movie’s end, the child’s biological parents return, demanding custody. Seeing their love for each other, the couple decides to give the child to Mimi, thus bringing a happy ending.

The glorification and essentialisation of motherhood

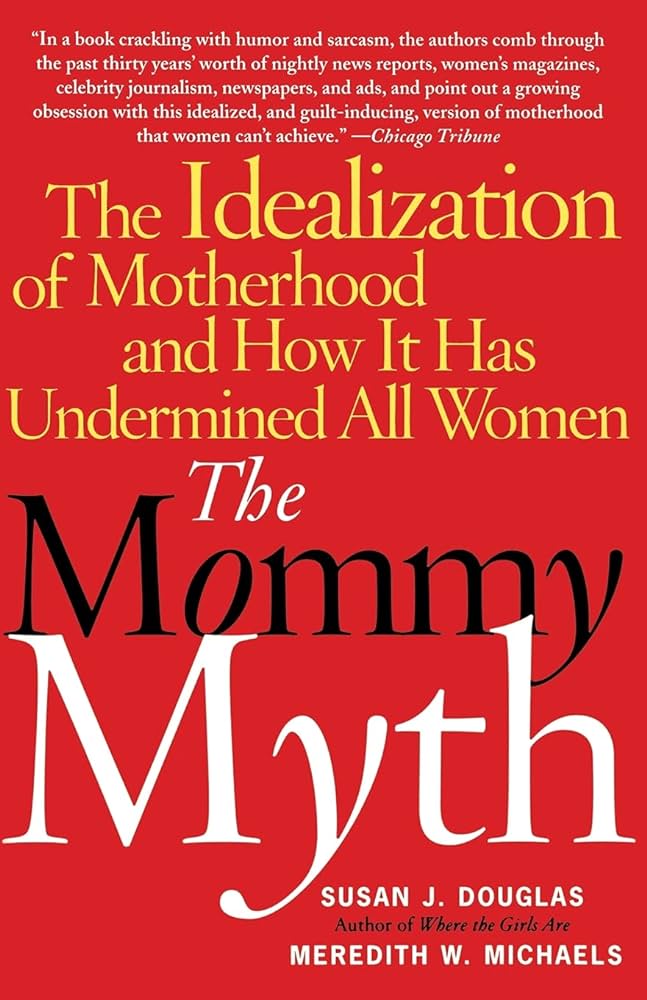

These movies, hailed as progressive retellings, often portray a deeply patriarchal ideology of motherhood as the sole purpose of a woman’s life. In Mimi, when the option of abortion is given to the pregnant Mimi, she rejects it by saying that it is a crime. The same is said in Aradhana and Kya Kehna. In Kya Kehna when the college drama team taunts the pregnant Priya, she says that she is already a mother and cannot kill her child. These ideas are rooted in the thought that propagates motherhood as the goal of a woman’s life, a concept discussed by Susan Douglas and Meredith Michaels in their book The Mommy Myth: The Idealization of Motherhood and How It Has Undermined All (2005) termed as the “Mommy Myth”, where there is an ‘insistence that no woman is truly complete or fulfilled unless she has kids.‘

However, these glorification only reflect how a male dominant society wants to accept a woman- only if she proves that she is not living her life for herself, but is living some someone else- especially for a son. It is also very noteworthy that in all the three movies discussed in this article, the children are boys. It again points to the ideaology of male savourism. The women in these movies are also hugely dependent on the male figures around then – fathers and brothers, and they eventually finds a purpose through the birth of sons. It can be said that the Bollywood representation of motherhood still is in its ‘Mere paas maa hai‘ era.

Through its mother characters, Bollywood has also set idealised standards of how a mother “ought to be”. The way she dresses and speaks, her relationships, her character and her morale are set according to the definitive norms that suit patriarchal stories and narration. A “modern” woman is still defined as a bad mother. This concept has taken a new form – women can be educated, liberated, and modern as long as they show maternal instincts.

Unplanned pregnancies in these movies often jump into a dramatic terrain, where the characters’ morality is showcased by referring to abortion as “murder”, followed by a monologue of the “virtues of being a mother”.

Unplanned pregnancies in these movies often jump into a dramatic terrain, where the characters’ morality is showcased by referring to abortion as “murder”, followed by a monologue of the “virtues of being a mother”.

On the other hand, when women choose their lives over pregnancy, they are deemed evil – for example, in Aitraaz (2004), the character of Priyanka Chopra is villainised as she decides to abort the fetus. However, in the movie, Shaadi Karke Phas Gaya Yaar (2006), (as foolish as the title sounds), the modern Ahana, played by Shilpa Shetty decides to abort the fetus once she discovers that she is pregnant. But, she transforms into an obedient housewife once she realises the purity of being a mother, a courtesy of her traditional husband, Ayaan, played by Salman Khan.

Maternalising the female identity

In all three movies, the female characters are depicted as vibrant individuals, each with their dreams and ambitions. But as the topic of pregnancy springs into the plot, their identities are erased by maternalising them. Here, motherhood is kept as the moral epicentre where the erasure of other identities is justified through the question of morality. Along with jittering the plot through the pregnancy, the films homogenise and glamourise the experience of motherhood.

When pregnancy outside marriage and accidental pregnancies are discussed, it comes with the baggage of social stigma and interpersonal struggles. While the bit of interpersonal struggles is dramatised, the question of social stigma is often neglected. In such a situation of social stigma and conflict, it is ridiculous to assume that the woman will only have maternal instincts. The films profoundly echo the sentiments of motherhood without challenging any patriarchal setup structured around it.

The narrative around unwed mothers remains intact and the stories woven around unwed mothers stay around the glorification and essentialisation of motherhood.

Therefore, the absence of a male partner in these movies does not mean the women are inherently feminist. They have to accept the dictums of patriarchy to live an acceptable life through extreme personal sacrifices. The minor progressive concessions in these movies, for example, Priya’s authority to decide her partner and Mimi’s ambition of becoming a heroine – are finally sacrificed to suit the patriarchal social order. However, the narrative around unwed mothers remains intact and the stories woven around unwed mothers stay around the glorification and essentialisation of motherhood.

About the author(s)

Hajara Najeeb is interested in topics concerning gender and minority rights. She also writes on cinema and its political implications. She has graduated from Tata Institute of Social Sciences.