Trigger Warning: Mention of Abuse and Rape

When the dust settled on the 1968 May Revolution in Paris, it was difficult to tell who had won the battle – the protestors or the police. But one thing was clear, the order of the day had been overturned and France would be born anew. For seven weeks or so, violent protests all over the country had shaken France down to its very roots.

The government had collapsed as President Charles de Gaulle had fled the country and throughout Paris reverberated the slogan: “Be realistic, demand the impossible!”

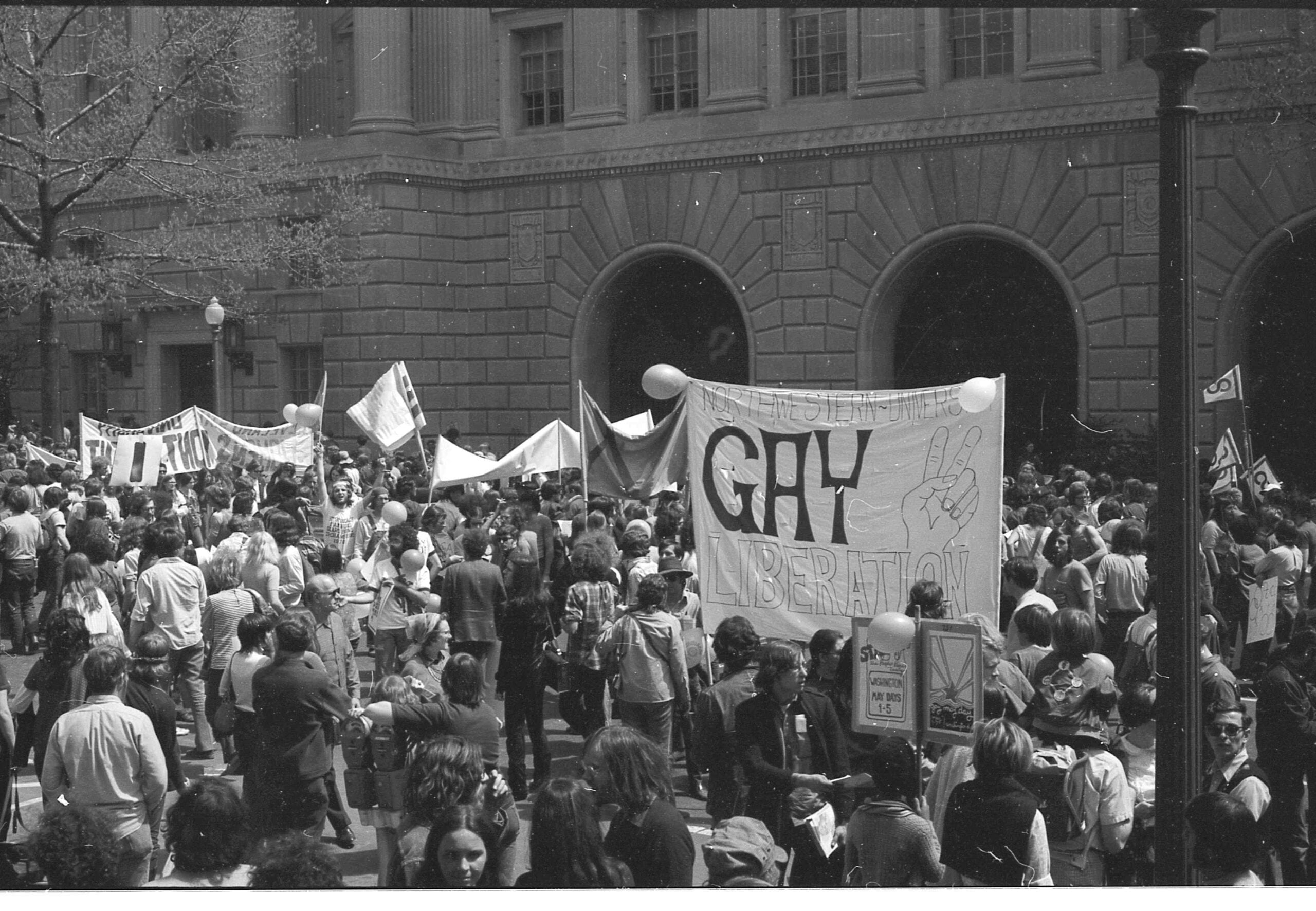

But while the New Left – the young vanguard of revolutionary communists that had engineered the revolution – lay mostly fractured in the aftermath of brutal police repression, the intellectual ferment of the time had given way to two massive movements that would see their heyday over the next decade: the Women’s Liberation and Gay Liberations movements.

Most people don’t realise how deeply invested the members of these movements were in the peddling of the New Left or how many ideas spilt over into the politics of the next decade, but many also remain unaware of the intense debate between the feminists and gay liberationists that ensued in the following years.

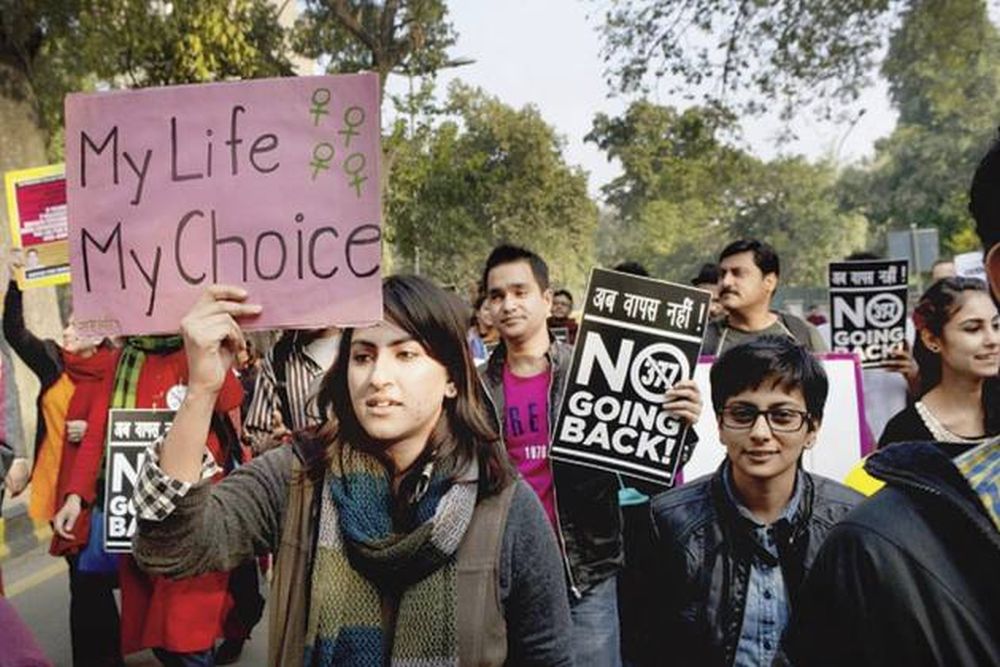

Tracing the history of their ideas reveals a complicated mix of solidarity and conflict, but some of these debates are perhaps still relevant to the contemporary Indian reader, as we’re still dealing with the question of the role of law in individual sexual freedom.

But before this, some context about the sexual revolution of the New Left is in order here.

The prehistory

1968 was a pivotal year on a global scale; in cities around the world, people took to the streets to protest oppression. Although there were widespread protests in the United States, Japan, Italy, Czechoslovakia and Poland, leaving neither communism nor capitalism out of the onslaught, the most spectacular of these protest movements definitely took place in France. Hundreds of thousands of students were joined by wildcat strikes that involved over 11 million workers, forcing the President to flee to Germany in hopes to secure military support from France’s neighbours in the event of a complete government collapse.

Despite all the rampant advocacy for free love, many leftist women concluded that their male comrades were no less misogynistic than the average French man. As one female student commented: “We did the cooking, made the sandwiches, looked after the guys… We were the revolutionaries’ maids.”

Very little reform actually came as a result of the protests, but the turmoil had arguably done much more. According to historian Michael Sibalis, the one permanent consequence of the May Revolution was the weakened respect for traditional authorities like the state and family, and the desire to radically break from the values and norms of ‘bourgeois‘ society. The act of sex was glorified as a revolutionary act, one that fundamentally threatened the status quo. On the walls of Paris was a bold declaration, “The more I make love, the more I want to make revolution. The more I make revolution, the more I want to make love.”

Despite all the rampant advocacy for free love, many leftist women concluded that their male comrades were no less misogynistic than the average French man. As one female student commented: “We did the cooking, made the sandwiches, looked after the guys… We were the revolutionaries’ maids.”

And so emerged the Mouvement de libération des femmes or Women’s Liberation Movement.

Also Read: Remembering Marsha P Johnson: The Drag Queen & Gay Liberation Activist

The MLF was a call to action, and at first, it was a call very similar to their sibling group, Front homosexuel d’action révolutionnaire or FHAR. Both these groups were established in the same year and initially shared members and goals alike. But things went south very quickly; in June 1971, two militants from the nascent feminist movement penned an article in Tout! magazine titled, “Your Sexual Liberation is Not Ours“, in which they argued that women in the New Left were “fixed in this [liberated] role and made to feel guilty when they no longer corresponded to it“, and that the experience of being “liberated” was no different from being “traditional“, except now it seemed that they owed the same sexual labour to many more men.

But the most formative debate of the coming decade would revolve around the usefulness of the law. On this matter, the men of FHAR unquestioningly agreed with their New Left predecessors, in whose eyes the law was only a tool of oppression and force, opting for a sexual libertarianism of sorts.

Among the feminists, on the other hand, there was growing advocacy for law as a necessary intervention in issues of sexual violence and abortion. Texts like Susan Brownmiller’s “Against Our Own Will” were translated into French and circulated widely in the country.

In June 1976, there was a Ten Hours Against Rape Demonstration event at the Mutualite meeting hall in Paris, which was completely closed off to men. Curiously, the fact that the meeting concerned rape provoked leftist men a lot more than the fact they were left out of it, according to historian Julian Bourg.

The pitfalls of using the same law that represses people were not lost on feminist lawyers and activists. Many were sceptical of how the conservatives could use rape laws to “punish” already marginalised communities or how the system itself was flawed to never benefit the victim as it placed the burden of proof squarely on victims themselves. They pushed for reduced sentences, the abolition of the death penalty and the introduction of reconciliation as a legal mechanism.

The desire to be “left alone” has had a long presence in the history of queer people, who’ve often been subject to state repression, familial violence and cultural mockery. To Guy Hocquengham, leader of the FHAR, paradise was a “dark homosexuality” – the world of Jean Genet, of sex workers, criminality, cruising and public sex. His diatribe was against anything that could canalise the movement into “reproductive heterosexual normalcy“, in other words, a life untouched by the law. To him, the fight for rape laws seemed to increasingly look like this; after all, rape laws directly intervene in people’s private space.

This view will probably seem reductive, even bizarre, to anyone reading it now. In India today, there are many laws that protect the individual in private spaces, like the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act (2012) or the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act (2005).

The pitfalls of using the same law that represses people were not lost on feminist lawyers and activists. Many were sceptical of how the conservatives could use rape laws to “punish” already marginalised communities or how the system itself was flawed to never benefit the victim as it placed the burden of proof squarely on victims themselves. They pushed for reduced sentences, the abolition of the death penalty and the introduction of reconciliation as a legal mechanism.

On the eve of September 6th 2018, a five-judge bench of the Supreme Court struck down a part of Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, decriminalising homosexual sex. The judgment followed the decision by a nine-judge bench in the Right to Privacy Act, which hinted at the wrongness of upholding Section 377 in light of this new law.

To the feminist movement, the law was a strategic tool to be used occasionally, not a death knell to all existing radical politics. Earlier this week, the Supreme Court of India referred a group of petitioners seeking the legal recognition of same-sex marriage to a Constitutional Bench, perhaps forcing us back to the question of the “strategic” use of the law.

Section 377 and privacy

On the eve of September 6th 2018, a five-judge bench of the Supreme Court struck down a part of Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, decriminalising homosexual sex. The judgment followed the decision by a nine-judge bench in the Right to Privacy Act, which hinted at the wrongness of upholding Section 377 in light of this new law. Spanning over 220 pages, what the Navtej Singh Johar Vs. The Union of India verdict reveals an in-depth dialogue about the place of law in personal life.

Despite spending around 100 pages out of the 220, listing how vital the law has been in preserving the idea of the individual, the judgment is ultimately shrouded in the logic of privacy. In referring to philosopher H.L.A. Hart, it defines sexual acts as issues of “private morality” in which the law has no interest, even adding that morality has no place in law.

Hocquengham’s sexual underworld was only seemingly free of hierarchy and structure and was no natural road to liberation. Many French progressives remained blind to how the rampage against social conservatism and “sexual taboo” doesn’t adequately address the question of agency and equality.

However, for the French feminists of the 70s and queer people of today’s unequal India, the sphere of “privacy” is not a free space at all, but one marred by all kinds of societal inequalities.

Hocquengham’s sexual underworld was only seemingly free of hierarchy and structure and was no natural road to liberation. Many French progressives remained blind to how the rampage against social conservatism and “sexual taboo” doesn’t adequately address the question of agency and equality.

In 1978, the French left was arguing that the act of rape was a justified act of revenge on the privileged classes for marginalised men, the gay liberationists were accusing feminists lawyers of becoming “ruthless Amazons out for revenge” for trying to prosecute sex offenders and almost every progressive had come to believe that feminists had sold out to “bourgeois” legality – a term that was used to explain anything that opposed the supposed working-class virility of the time.

In the aftermath of the Navtej Singh Johar Judgment, many queer people rejoiced at the idea of being “left alone“. While this is a natural reaction after seven decades of being criminalised, the next step is a lot more complicated. The shortcomings of this judgment have been made very clear by the Centre on March 12th.

While these two contexts are very different, there is a striking similarity between the two battles; a question of what the law does. Does it liberate or does it oppress? Is the private sphere a place of non-interference or a right that is safeguarded by the law? For the French feminists, who once became “revolutionary maids” in the absence of law, the temptation of privacy from the law only seemed attractive insofar as it did not oppress them. But beyond that, freedom from the government and law was a false promise that just reconstituted the inequality of the sexes in the shiny veneer of endless liberty.

In the aftermath of the Navtej Singh Johar Judgment, many queer people rejoiced at the idea of being “left alone“. While this is a natural reaction after seven decades of being criminalised, the next step is a lot more complicated. The shortcomings of this judgment have been made very clear by the Centre on March 12th. In response to the pleas for the recognition of same-sex marriage, the Centre contended that the Navtej Singh Johar judgement has no implications on the issue of marriage, stating, “Any formal recognition of such a human relationship [marriage] cannot be regarded as an issue of privacy.”

While the Centre’s belief that heterosexual marriage is a “quintessential building block of the State” might seem arbitrary and unjust, their point that marriage isn’t a matter of privacy is, unfortunately, a sound argument.

The legal recognition of marriage has implications for issues such as adoption, inheritance and property rights. There is no doubt that any disputes about such issues cannot be extrapolated from the “private morality” that the Navtej Singh Johar judgment constantly prioritises.

Decades before this, feminist law warned us against the ambiguity and injustice of the so-called “private sphere” by thrusting issues of sexual violence, abortion and childcare into the domain of positive freedoms. Similarly, the legal recognition of same-sex marriage would be a positive right, if it ever materialises. It is, inarguably, a public right which will have implications on equality, safety and our right to exist in this country.

As the Supreme Court hearings begin, perhaps queer people of India will have to grapple with a plight very similar to that of the Parisian feminists of the 1970s.