Since childhood, my mother told me stories of Babasaheb, Ramai, Savitribai and Jyotiba Phule which impacted me in a certain way to uphold their vision as a way of life just like my parents. Thus, during my early years, I never felt there could be any discrimination based on my gender until one day.

I was born in a lower-middle-class Bahujan family in the 90s, with my parents being very progressive for their times. I have another sibling who is also a girl and this fact was celebrated by my parents. We never grew up with confined gendered norms of pink and blue. Both of us girls were raised in a very gender-neutral manner by my parents. We were never told to dress a certain way. Or behave in a certain manner, or learn certain skills.

This sense of equality in my parents is attributed to being Ambedkarite Buddhists.

One day during a Rakhi function, one of my aunts suddenly expressed her disappointment in my father not having a male child to take care of him and my mother in old age. For me, this suddenly came like a shock. I was in class 3rd and my mind could not digest the contempt that she had expressed her feeling. She was my aunt and she loved me, still, she wanted a boy instead of me or my sister. Why? Are we not good enough was the question ringing in my head.

My father protested against her statement but that could not invoke a sense of contentment in me and I decided at that age that I want to prove her wrong by becoming a son to my parents. Since then, I hated frocks and skirts. I wanted to dress in a masculine way and wanted to be more masculine or boy-like. I am using the terms “boy” and “girl” to make this distinction as at that time I had no idea about how diverse gender is.

Also Read: Pride And Power: Dr BR Ambedkar Through A Dalit Feminist Lens

I even asked my parents to not call me “Sanchi” a girlish nickname but anything else that sounds more masculine. I hated going to school wearing a skirt, as now for me that was feminine which I did not want to portray myself as. By that time my sister was also admitted to the same school and just like a brother protects a sister I took that onus on myself to protect her. I even made her tie Rakhi to my wrists on Raksha Bandhan.

But the inner me was always insecure as now I was living a dual life trying to be something that I am not. It kept on affecting me as I grew and I became reticent. Till I reached 10th grade, my friends used to tease me that I have forgotten how to laugh. This burden of becoming my parent’s son by now had taken a mental toll on me and that is when my parents noticed that something was wrong with the way I have been behaving.

I reiterated it in a sense that when all humans are equal how could a man be more of an asset to society and not a woman? But being a woman also does not mean that I was again to dress and look like one. This was the first time that I felt empowered in my identity, the way I was.

I confessed to them about how I felt being the elder daughter and not a son. They made me understand that they were happy with us and had no issues and that what I was thinking was wrong. This is when I embraced equality again.

Also Read: On Ambedkar Jayanti: Revisiting Babasaheb’s Feminist Ideas

I felt relieved but then was I supposed to change? This was a big question. And I found my answers in the writings of Babasaheb. “I shall believe in the equality of man” is one of the 22 vows that I have been repeating and reading as a part of the 22 Vows that Babasaheb had bestowed on the Nava Buddhists.

I reiterated it in a sense that when all humans are equal how could a man be more of an asset to society and not a woman? But being a woman also does not mean that I was again to dress and look like one. This was the first time that I felt empowered in my identity, the way I was.

As I moved to college to pursue my Engineering, I heard the word feminism in a rather negative way. The women who hated men and competed with them over every petty thing were called feminists in an annoying way which the women also took pride in being called so. I was again confused as to what exactly is feminism, is it hating the men around you? Fighting with them to claim power or intellect? What exactly is it?

And yet again I seek my refuge in Babasaheb. “I measure the progress of a community by the degree of progress which women have achieved” were his words. It was through these words I made sense of what feminism was. It was not hating the men but believing in the equality of both men and women. It was not about competition but about demanding equal rights for both. I got my sense of feminism cleared since then.

As I came to JNU for my Masters, I started reading Babasaheb’s writings in a more detailed manner and yet again a question arose in my mind. Am I a Bahujan feminist or a feminist Bahujan? Both identities mattered to me and here I was standing at the crossroads of it. That is when I learnt of intersectionality which dealt with both caste and gender and so I reflected on my experiences back to the days of Engineering when my Training and Placement officer at the University did not allow me to appear for an interview despite me fulfilling every criterion to sit for it only for the reason that I had wished to pursue preparing for a government job instead of a private one in my database which was with the Training and placement cell.

“Oh, you belong to the reserved category? Then why do you want to appear for the interview for a private job? You wish to go for a govt job right, there are quotas there you will easily get in there and those are comfortable for girls compared to a private one.” These were his words which were against both my identity as a woman and as a Bahujan woman. This reflection helped me to understand how discrimination happens in layers superimposing caste upon gender for many women like me.

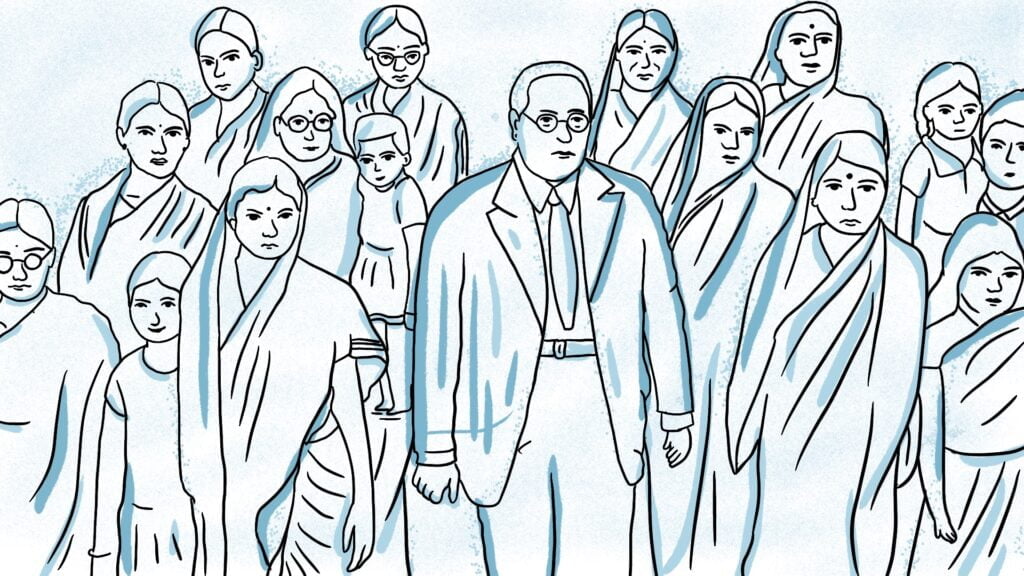

Babasaheb in his writings “Revolution and Counterrevolution in Ancient India” and “Riddles of Hinduism” talked about women’s rights at a time when social structures were still traditional and deeply caste-driven and showed how Dalit and other oppressed caste women were doubly marginalised in this social structure. Babasaheb was a firm believer in the notion of ‘Sudhaaranaa,‘ or development, which entailed fostering women’s intellect and self-development through education.

“Knowledge and learning are not for men alone; they are essential for women too…if you want Sudhaaranaa for future generations, educating girls is very important. You cannot afford to forget my speech or to fail to put it into practice,” Babasaheb stated in the 3 February 1928 edition of “Bahishkrut Bharat,” a journal he created.

Babasaheb’s significant contribution to women’s rights was his efforts in the 1950s to enact the Hindu Code Bills. His enthusiasm for the Bills stemmed from his desire to protect women’s right to property, which was denied to them in ancient Hindu legal texts such as Manusmriti and Dharmashastras. Women’s only traditional property was ‘Stridhan,’ which restricted rightful access and was only feasible inside an endogamous marital social framework.

A woman became the absolute owner of her land under Section 14 of the Hindu Succession Act of 1956. Section 6 of the Act also abolished the exclusive inheritance of property by male family members and gave Hindu women the same privilege.

Babasaheb’s vision and writings empowered me throughout the course of my life both as a Bahujan and as a woman. On campus, we always burn Manusmriti the same day that Babasaheb burned it and putting that document into the burning fire gives me a sense of freedom and equality.

Since childhood, we have been greeting each other by saying “Jai Bhim” Now every time I say that makes me feel emancipated from all the restrictions that the male-dominated social order tried to tie me up with. This is something that every Bahujan women feel when they say “Jai Bhim” but despite having immensely contributed to women’s empowerment, Babasaheb has been rarely looked up to as a feminist but always reduced to being a Dalit icon.

Also Read: Gaining Confidence In My Feminist Identity

And that is why I have decided to further Babasaheb’s vision as a feminist through academics so that many more women like me grow up getting empowered by reading him and following his legacy.

About the author(s)

Preeti Patil is a learning enthusiast. She has completed her master's in Politics with a specialisation in International Studies from Jawaharlal Nehru University. She graduated in Electronics Engineering from RTMNU. Her area of interest is Gender studies, feminist security perspectives, Dalit feminism, Caste & diaspora & affirmative action policies.