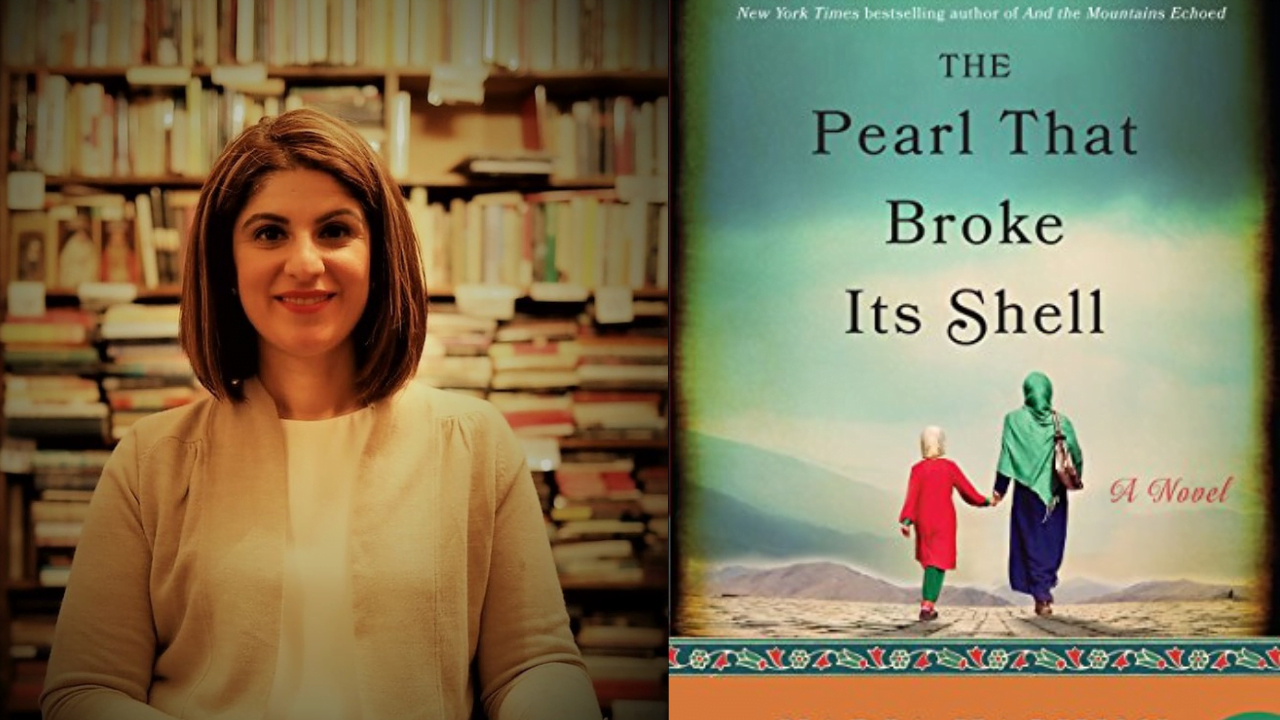

The Pearl That Broke Its Shell by Nadia Hashimi follows Rahima, a young girl in the city of Kabul. With no male heirs in the family, she finds herself as the family’s new bacha posh. The tradition of the bacha posh has been prevalent in Afghanistan as well as some regions of Pakistan for centuries. The translation of bacha posh from the local Dari language means “a girl dressed like a boy.”

Often, in families who solely bear daughters, a young girl is chosen as a bacha posh or bacha poshi, to act as a pseudo-son for the family. The girl, now designated as a boy, performs the duties that would typically be performed by the sons after cutting her hair and dressing in the traditional male clothing of baggy pants and a long shirt.

The bacha posh can receive an education, play sports, accompany his sisters outside the house and help his father in his profession. Activities that as a girl, she never would have dreamed of doing. Simply the right to be outside alone without a male present is unspeakable for women.

The tradition stems from the heavily male-dominated, patriarchal society of Afghanistan. Although its roots are in women’s inequality, it gives young girls a taste of what it is to be a male, i.e., of what it is to be free. Today, wearing pants or going out for a stroll with your girlfriends are very standard activities for most women, almost a fundamental human right. Yet, as is visible in the tradition of the bacha posh, these activities are only necessitated for women due to the lack of men.

Also Read: The God Of Small Things: The “Big” And “Small” Things In It

Rahima, now known as Rahim, soon learns from her aunt Kala Shaima that she was not the first woman in her family to take up the responsibilities of a male in the family. Her great-great-grandmother Bibi Shekiba, after facing many trials and tribulations of living as an unmarried woman with an unruly family, finds herself at the palace, serving as a bacha posh for the king’s harem.

For most of her life, after her face was marred due to an accident with hot oil, Shekiba was never acknowledged as a woman. While she never had the freedom of a bacha posh until she joined the service at the palace, in her family, she was treated as an outcast, neither woman nor a man.

“But I have always been my father’s daughter- son. My father hardly knew I was a girl. I have always done the work a son would do. I am not to be considered for a wife, so what is the difference? What of me is a girl?”

When Shekiba was needed in terms of hard labour and work around the house, she was called. She would carry heavy pails of water, and lift the firewood, all labour-intensive tasks. Yet, when the opportunity of inheriting her father’s property came about, she was shunned. Why? Because she was a woman and a woman could not inherit her father’s property, let alone live on that property unmarried, by herself. Her only path to freedom was leaving her exploitative family and becoming a bacha posh.

The novel wanders to and fro between the tales of the two bacha posh, one in the early 1900s (Shekiba) and one in the early 2000s (Rahima). Although the stories are literally a hundred years apart, the reader is able to grasp the similarities and consistencies in the treatment of women over time, in the country of Afghanistan.

The women in this society are highly objectified, tossed around here and there, for the overall welfare of the family. When it is convenient for them, a woman can perform the tasks of a man. However, when it is not required due to the presence of a male heir, their status is reduced to nearly nothing. Not to mention how extremely traumatising it must be to grow up with the freedom and joys of being a strong, confident boy to the restrictions of the house and marriage after puberty hits.

Ultimately Rahima gets a proposal for marriage from the local warlord, Abdul Khaliq after having been a bacha posh for much too long. She has to unlearn her ways and relearn the etiquette of being a woman in society.

“In the meantime, Madar-Jan had to undo what she had done to me. She gave me one of Parwin’s dressed and a chador to hide my boyish hair. She gave my pants and tunics to my uncle’s wife for her boys. “You are Rahima. You are a girl and you need to remember to carry yourself like one. Watch how you walk and how you sit. Don’t look, people, men, in the eye and keep your voice low.“

Shekiba finds her way around palace life with her strength from years of manual labour giving her an edge as a bacha posh guarding the harem. She tries to pursue the prince in order to find her way out of this life. However, she gets caught up in preventing an affair with a woman from the harem and is sentenced to 100 lashes.

Eventually, she is saved by a proposal from a court advisor and leads a comfortable life. Rahima struggles at her marital home and is desperate to find a way out. After being a bacha posh for so long, she is trapped in a household as one of the many ill-treated wives of Abdul Khaliq. Slowly she finds a way to Kabul as a woman representative from her husband’s political party and with the help of Ms. Franklin, a teacher at the resource centre, escapes to a women’s shelter.

Both Shekiba and Rahima had gotten a taste of freedom. Yet, the only way they could eventually find space was through the marriage of a powerful man in the case of Bibi Shekiba or escaping the marriage and family life itself as Rahima did. They never indeed retained the characteristics they had picked up as a bacha posh, it merely helped them to reach another point in their lives as women in a relatively better position. Previously, they had lived the life of a man with the freedoms, opportunities and accessibility that men have in a society where women are practically invisible.

Also Read: Understanding The African American Experience Through James Baldwin’s “Notes Of Native Son”

Going back to the life of a woman after that is not an easy transition to make. While the tradition of a bacha posh has its temporary benefits for the family, in the long run, how does it help women, except degrade their status even more?

The implications of the tradition of the bacha posh indicate that the only way to be strong, free and independent is by being a male. Instead, in a family full of women, the women should be given the opportunities that men have for the care and welfare of their family, as we can see from both Shekiba and Rahima, women are definitely more than capable.