Mismatched is a GenZ drama that merits many articles. The significance of trust and sharing vulnerabilities in friendships, exploration of sexual identity and intergenerational responses to queerness, commentary on class in urban settings, how religious plurality is apparent without mention, centring of technological education, relationships to the West and identity struggles for children of the diaspora – it is full of relevance for contemporary India and Indians living worldwide.

What is particularly promising to us is not just the portrayal but also the reception of Mismatched with GenZ audiences. The resounding excitement of the fan base packed to the rafters at each public viewing is a clear indication that the series touched a nerve and a pleasant one at that.

As an audience of an older vintage and of two different generations, it is a relief for us to witness the departure of the typical male protagonist of our youths. The eve-teasing, consent-optional men of the 80s and 90s where heterosexual passion was often depicted as overpowering and uncontrollable.

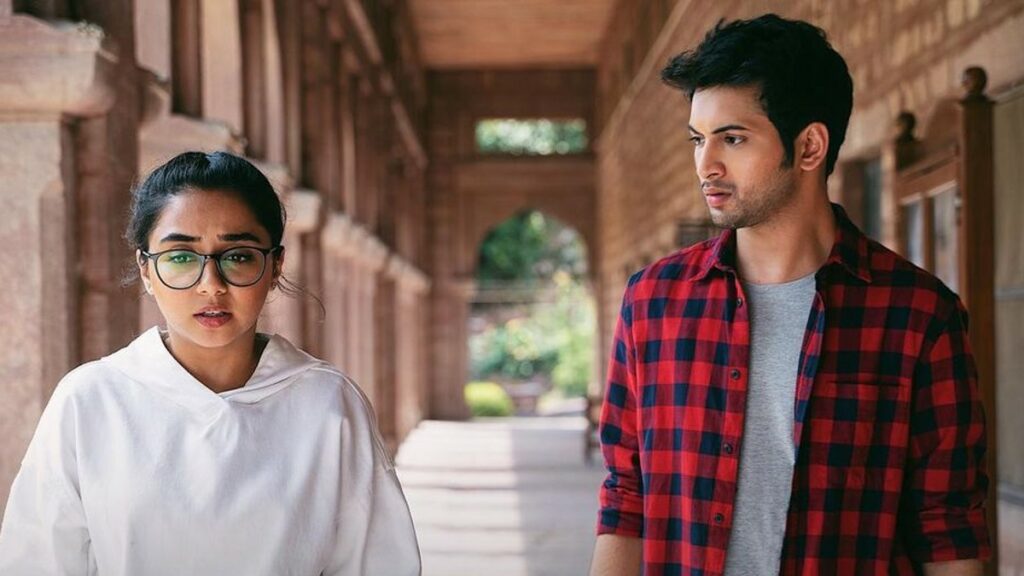

Instead, the permission-asking, respectful love interests of the main character Dimple Ahuja, made us heave a collective sigh of relief. Perhaps, our daughter’s generation will not have to work so hard to be heard.

Without claiming to be overtly feminist, Mismatched easily passes the Bechdel test – the several women characters have a lot to say to each other, but a lot of it has nothing to do with the men in their lives. The plot is propelled by the choices of the central female character whether romantic or academic – repeatedly iterated through the narration of her ambitions, her confusion between the two male interests and her choosing and rejecting them through the narrative moves the story along.

As an audience of an older vintage and of two different generations, it is a relief for us to witness the departure of the typical male protagonist of our youths. The eve-teasing, consent-optional men of the 80s and 90s where heterosexual passion was often depicted as overpowering and uncontrollable.

Dimple is dreamy and googly-eyed – not about men but coding, making apps and owning her own company. Along the way, she falls in love, has crushes and changes her mind. Dimple is not a passive recipient of her relationships, she is an active participant who has multiple ambitions and a clear sense of identity outside of her relationships with men.

Both Rishi and Harsh, on the other hand, prioritise their relationship with Dimple over their respective careers even though it’s clear they have much promise and much at stake, whether it is Rishi wanting to drop out of the summer course or Harsh considering rescinding his offer at Berklee School of Music. While it deserves a mention that both the male protagonists come from more privilege than Dimple who is clear that she has to make her own way in the world.

The tale of Anmol presents us with a nuanced introspection into the life of a character whom we might otherwise be quick to fit into the category of ‘bad boy,’ Looking solely at his consistent swearing and bullying of peers does not tell the full story of Dimple’s apparent nemesis and misogynistic, gaming competitor. Anmol is a person with a disability who is hurting, facilities across the school are inaccessible to his needs and his confinement to a wheelchair appears to deprive him of the romantic interest he witnesses peers receiving – the world is a ‘marathon,’ and full of ‘chutiyapa,’ (fuckery).

The turn for Anmol occurs when his Professor presents him with an ultimatum, expulsion for beating a fellow student or going to therapy. He chooses the latter. Feeling signalled out, he struggles to trust the process and honestly answer questions posed by his therapist – a visibly Sikh man. Confused by this ‘mental masturbation,’ he declares ‘sharing and caring zaroorat nahi hain,’ (sharing and caring is not necessary).

With time, he begins to lower his guard – demonstrating courage in dialogue with fear and loneliness – grappling with versions of his own self that pass shameful judgements on his condition. He struggles, however, to respect the platonic affection of Zeenat Karim – who supports his otherwise secretive therapeutic journey – and he makes a move which is not reciprocated.

While anger remains his default response in such moments, there is hope. Group therapy sees him confront his toxic online presence, the tale of Vinny – a young woman who has been abused by men online – sparks a deeper reckoning. Series two ends with a suggestion of romantic interest and support for his proposal to design an app for persons with disability.

We remain hopeful that Mismatched will continue to chart the way for an even more defined non-toxic masculinity and offer some more male role models.

Questions for our male protagonists moving into Mismatched 3

- Seemingly less ambitious than his “future wife,” Dimple Ahuja, Rishi Shekhawat’s journey is a confused one. While his filmy hopes seem to be coming to life, can we expect a change in his relationship with his father, reflection on his unfair treatment of Sanskriti and strengthening of friendship with childhood bestie Namrata Bidasaria?

- A heartbroken musician who finds strength in his capacity for empathy, Harsh Agarwal declares his ambition to be a “forever boi, not a fuck boi,” at the end of Series Two – will this child of the diaspora find the romantic reciprocity he deserves?

- Anmol Malhotra’s therapeutic journey sparks a change in his relationship with himself and his peers – the arrival of acceptance and a shift away from bullying and sexual jealousy. So, what can we expect in Series Three – will he be able to love Vinny?

- Mismatched is yet to portray queer masculinities among Indian GenZ. There is both queerphobia expressed by some men and a sweet intergenerational exchange between Celina Matthews and an old man who notes “pyar bahut achi baat hai, chahiye kisi se bhi ho,” (love is a very good thing, whoever it may be with). Will queer male protagonists appear alongside cis-het men Rishi, Harsh and Anmol in Series 3?

- Will Mismatched Series 3 make more explicit references to and critically engage with the caste privileges of its lead characters?