A source of popular entertainment and a subject of academic interest, cinema is a unique mixture of art and business that profoundly influences culture. No more so than in India – where far more films are released per year than anywhere else. There is a growing presence of Hindi cinema at global film festivals and film songs dominate charts across borders.

Yet, in our present moment of propaganda movies and divisive politics, there is an imperative need to critically explore future trajectories. We can learn to ‘use the future’ to identify new questions and action that can transform our present.

The present state of Hindi cinema

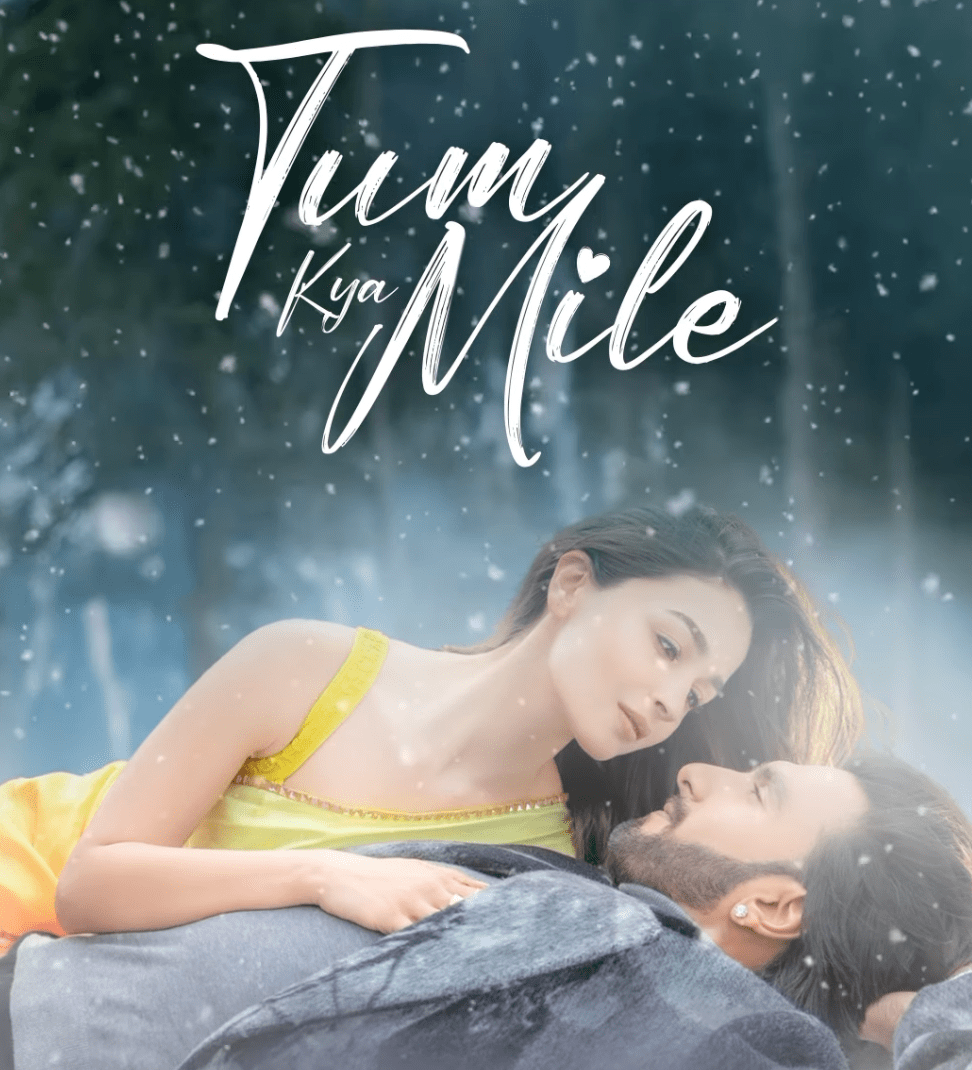

Reflecting on the present, culture and entertainment journalist Takshi Mehta notes that though Hindi cinema has ‘come a long way, it repeatedly shows women and queer people with discrimination, and champions toxic masculinity.‘ The notion of women as ‘docile creatures who are not equal to men‘ is often reinforced. There has long been a patriarchal gendering of fashion in movies too. We need only look at the music video for the song ‘Tum Kya Mile’ from the recent film Rocky aur Rani ki Prem Kahani (2023) to see the continuation of this trend – dancing atop snowy mountains, Alia Bhatt is seen in chiffon sarees, while Ranveer Singh wears multiple layers.

According to Aseem Chhabra – a film journalist, biographer, and director of the New York Indian Film Festival (NYIFF) – while there are ‘some politically and socially aware young filmmakers,‘ cinema simultaneously ‘reflects prejudices and inequalities in society around class, caste, gender, sexuality and religion.’ Furthermore, there is a dissonance between socially conservative films that reflect ‘gender stereotypes‘ as in Raksha Bandhan (2022), and a film like Badhaai Do (2022) that represents ‘queer relationships, as progressive, fun and yet shows the strains in society.‘

Turning to the data, economist and author Shrayana Bhattacharya cites the O Womaniya report which states ‘less than 10% of films are produced by women‘. In her book Desperately Seeking Shah Rukh: India’s Lonely Young Women and the Search for Intimacy and Independence (2021), Bhattacharya reveals that women speak for a mere ‘12% of the time in Hindi cinema’s biggest hits‘. As Chhabra adds, the industry still believes that a ‘male star opens the doors and brings people to the theatres – it is a huge problem.‘

Probable futures of Hindi cinema

Considering factors that could shape a likely future, Mehta refers to Islamophobic propaganda movies – The Kashmir Files (2022) and The Kerala Story (2023) – and suggests rampant Hindu nationalism may translate into more such films. These ‘directly impact gender and sexuality and how we see Muslim women on screen,’ enforcing problematic narratives of ‘saviours and protectors.’ Bhattacharya adds that movies which ‘pander to hate and revise historical facts‘ have an ‘aesthetic‘ and ‘ugliness‘ that is ‘creating a market of their own.‘

Considering factors that could shape a likely future, Mehta refers to Islamophobic propaganda movies – The Kashmir Files (2022) and The Kerala Story (2023) – and suggests rampant Hindu nationalism may translate into more such films. These ‘directly impact gender and sexuality and how we see Muslim women on screen,’

More encouragingly, however, Mehta believes we will see ‘pay parity slowly but surely‘ for leading female actors as well as more women ‘saying no‘ to doing films that treat them as ‘arm candies.’ Bhattacharya concurs, noting ‘the era of female superstars is here and may continue.’ That said, there will still be ‘very different portrayals‘, from expressions of agency to a cheerleader for a male lead: ‘we will see an Alia Bhatt doing a Darlings (2022) and we will also see an Alia Bhatt doing a Brahmastra (2022).‘

Highlighting the impact economic trends may have on cinema, Bhattacharya refers to a K-shaped recovery from the pandemic, noting that while India’s ‘top 10% can engage in some luxury consumption, the giant 90% of the economy is vulnerable and in debt‘. This may lead to a ‘stagnation‘ in regular theatregoers and a greater ‘splintering in types of cinemas we are consuming.’ The emergence of niche markets may also continue given the increase in popularity of ‘regional cinema‘ and ‘OTT platforms.’ As Chhabra notes, this includes more ‘Tamil, Malayalam and Kannada films‘ being dubbed into Hindi for a growing North Indian audience.

Desirable futures of Hindi cinema

Painting images of the future that resonate with our desires, Bhattacharya imagines a world where everyone has the ‘purchasing power to go to the cinema hall more than once a month and watch a movie they want.‘ Not only is this about economic access, but the social function of films too – ‘the magic of being in a giant space with strangers!‘ Bhattacharya hopes for a ‘healthier cinema’ for women, where ‘different bodies are loved on screen.’ Mehta too wants women to ‘stop having to show skin‘ for the purpose of ‘titillating an audience.‘

Furthermore, she wishes for women to lead in the telling of their own stories – ‘why does she need the help of a man as seen in Pink (2016) or Dangal (2016)?‘ In an ideal future, Mehta envisions a turn away from the ‘chest-thumping masculinity of Baahubali (2017), RRR (2022), KGF (2022), and Pushpa (2021)‘, and instead the emergence of a healthier, ‘aspirational‘ masculinity. She hopes for a romantic revival and ‘tenderness in films‘, coupled with an awareness for consent and respect that was often found wanting in the romantic movies of the 1990s and the early 2000s.

Chhabra would like to see Hindi cinema grapple with the complexity of Indian history in a fashion akin to German films after the horrors of Nazism. In a future without ‘censorship, jingoism and political party interference,’ cinema would be able to highlight ‘the reality of stories and challenge society, without the fear of being shut down.’

The reframe

In the field of futures studies, ‘reframes’ are custom-made scenarios. They are designed to invite reflection and challenge the assumptions revealed in our imaginings of probable and desirable futures. So, what might be alternative futures of Hindi cinema and its representations of gender?

The industry has splintered into diverse niches. There is value for equal pay. There is a demand for representation of intersections in identity to be front and centre. Cinema believes it has a responsibility to challenge dominant socio-political narratives as well as hold the power to manipulate or reshape them. Portrayal of romance comes with the interplay of realism and fantasy. Internationally, Hindi cinema is not exoticised. Viewers want cinema that entertains.

Reflecting on this scenario, Mehta notes a need to ‘snap out‘ of the remnants of a ‘colonial hangover‘ – namely efforts to ‘mimic narrative styles and appease the West.‘ She calls for a critical assessment of the politics shaping Indian submissions for ‘Western film festivals and award shows.’ Chhabra highlights assumptions that a ‘star-driven industry‘ will continue and that OTT platforms are only searching for ‘eyeballs.’ This could have consequences for independent films, where more ‘meaningful narratives‘ are found.

Chhabra provides the example of Masaan (2015) – a story that ‘critically engaged with caste, a heart-breaking film that moves without actors needing to break into dance or song.’ There is also Jhini Bini Chadariya (2021), ‘a story about a Muslim weaver and a Hindu woman who is a dancer‘. These are the ‘real stories‘ being produced across India, exploring ‘characters in all their complexity.‘

Engaging with portrayals of romance in Hindi cinema, Mehta calls for ‘believability.’ Directors should do away with ‘monotonous impressions of what love looks like‘ and take inspiration from Cheeni Kum (2007) and The Lunchbox (2013), films which depicted love with ‘real-world complexity.’

Engaging with portrayals of romance in Hindi cinema, Mehta calls for ‘believability.’ Directors should do away with ‘monotonous impressions of what love looks like‘ and take inspiration from Cheeni Kum (2007) and The Lunchbox (2013), films which depicted love with ‘real-world complexity.’ Indeed, ‘life is not a Bollywood film with Shah Rukh Khan spreading his arms as much as you wish it to be.’

There is also a taboo to be addressed around nuanced portrayals of female sexuality and pleasure, as seen in Lust Stories (2018 and 2023) and Lipstick under my Burkha (2016). Mehta highlights the need to deconstruct ideas of the ‘good woman‘ who ‘doesn’t drink, doesn’t smoke, saves herself sexually for her husband‘ and the ‘bad woman who has sex without marriage, drinks and smokes.’ Such a dichotomy ‘is not how real-life works,‘ a ‘responsible‘ cinema would challenge such stereotypes.

Seeing cinema as a forum ‘to entertain, ask questions and tell stories,‘ Bhattacharya calls not only for the audience to sit with ‘discomfort‘ but makes a ‘big pitch for fantasy‘ too. In an unequal society and brutal economy, ‘particularly for women and marginalised communities, fantasy is needed.‘ This is not a lesser genre. In fact, ‘we should be encouraging and indulging in people’s fantasies, making great sci-fi films and big romantic soppy fantasies.‘

Furthermore, Bhattacharya challenges the fundamental assumption that ‘the audience is foolish and wholeheartedly consuming films.’ Her research proves otherwise. Indeed, a person she spoke to regarding the Shah Rukh Khan blockbuster Pathaan (2023) suggested it is ‘even more mythical than Shah Rukh’s love stories because no man would ever be comfortable with Dimple Kapadia as their boss.‘ Reflecting on the reception of Kabir Singh (2019), while some critiqued its ‘glorification of a certain kind of masculine partner‘, there were ‘equally the same numbers who were shocked and yet found the film thrilling too.’ As Bhattacharya shows, this is the ‘complexity of the cinema-going audience.‘ Yet, such perspectives from outside ‘hallowed status halls‘ are rarely listened to, nor are they considered ‘legitimate.’

New questions and next steps in Hindi cinema

Assessing how we can ‘use the future’ to transform representations of gender in Hindi cinema today, Chhabra calls for reflection on the ‘ways we watch and engage with films,’ asking ‘why should men doing the ‘bare minimum’ in households be celebrated in our stories?‘ In a country of ‘hurt sentiments’ and an ‘image conscious government,’ Mehta hopes that cinema can become more critical and challenge prejudices rather than obey the commands of a vocal few – noting ‘is it really cinema’s job to protect and promote the sentiments of the powerful?‘

In a present where dissent is clamped down on and bigoted opinion is ‘actively harming people’s safety,’ Bhattacharya calls on us to ask: ‘what is the judicial and institutional incentive for fearless filmmaking?‘ Furthermore, she draws attention to a historical lack of ‘willingness‘ of film institutes to provide ‘scholarships for women and invest resources in people from historically excluded communities who want to make films.’ This is a vital step to ‘democratise who gets to tell stories’. Indeed, ‘diverse minds‘ in front and behind the camera would be ‘game changers.’

Highlighting a need for ‘robust‘ analysis, Bhattacharya advocates for a ‘data-based conversation‘; this means not only gender but ‘caste breakdowns’ with regards to the ‘production, editing and direction of films and on-screen dialogue time.‘ Through consistent analysis of such data, we can ‘hold a mirror to who and where we really are.’

Imagination has a vital role to play in inspiring hope and action to transform a dangerous present. In exploring different visions of the future and challenging assumptions, we can move towards answering our shared question: ‘can we unite the people of India through stories?’

Imagination has a vital role to play in inspiring hope and action to transform a dangerous present. In exploring different visions of the future and challenging assumptions, we can move towards answering our shared question: ‘can we unite the people of India through stories?’

Insights drawn from ‘Futures of Hindi Cinema: Representations of Gender’ – an online event on Tuesday 06 June 2023. It featured Takshi Mehta, Shrayana Bhattacharya, and Aseem Chhabra. This public conversation was facilitated by Kushal Sohal, a Futures Literacy Designer. Sohal and Mehta co-designed the event. Mehta provided inputs to the writing of this article.

About the author(s)

Kushal Sohal is a futures literacy designer who works with intergovernmental agencies, universities, and collectives on futures of gender and related themes