If Lust Stories 1 was a stroke of pure genius, the emperor of cinematic bravado, then its sequel Lust Stories 2 is most certainly the empress of bland. The storytelling of the quartet in Lust Stories 1 -Dibakar Banerjee, Zoya Akhtar, Anurag Kashyap and Karan Johar was tight and bold and in the limited screen time, they managed to weave a rich tapestry of love and lust, with dollops of wit and sarcasm thrown in. Lust Stories 2 which again is an anthology of 4 stories by Balki, Sujoy Ghosh, Ravindernath Sharma and Konkona Sen Sharma hardly excites the viewer in terms of thematic content, plot constructions or characterisations; with the sole exception of Konkona Sen Sharma.

In a limited celluloid time, Konkona Sen Sharma’s ‘The Mirror‘ manages to address the idea of lust through the lens of class, gender and space.

The storyline is simple. Isheeta (played by the very versatile Tilottoma Shome), is a woman with some social and financial standing as is apparent through the opening shot of her- eyes shod in fancy shades, driving a car, and having a conversation with a friend about financial investments. The conversation is in chaste English -the language of the privileged and as Isheeta gets the car to the parking lot of a Mumbai high-rise, the class credentials are well established.

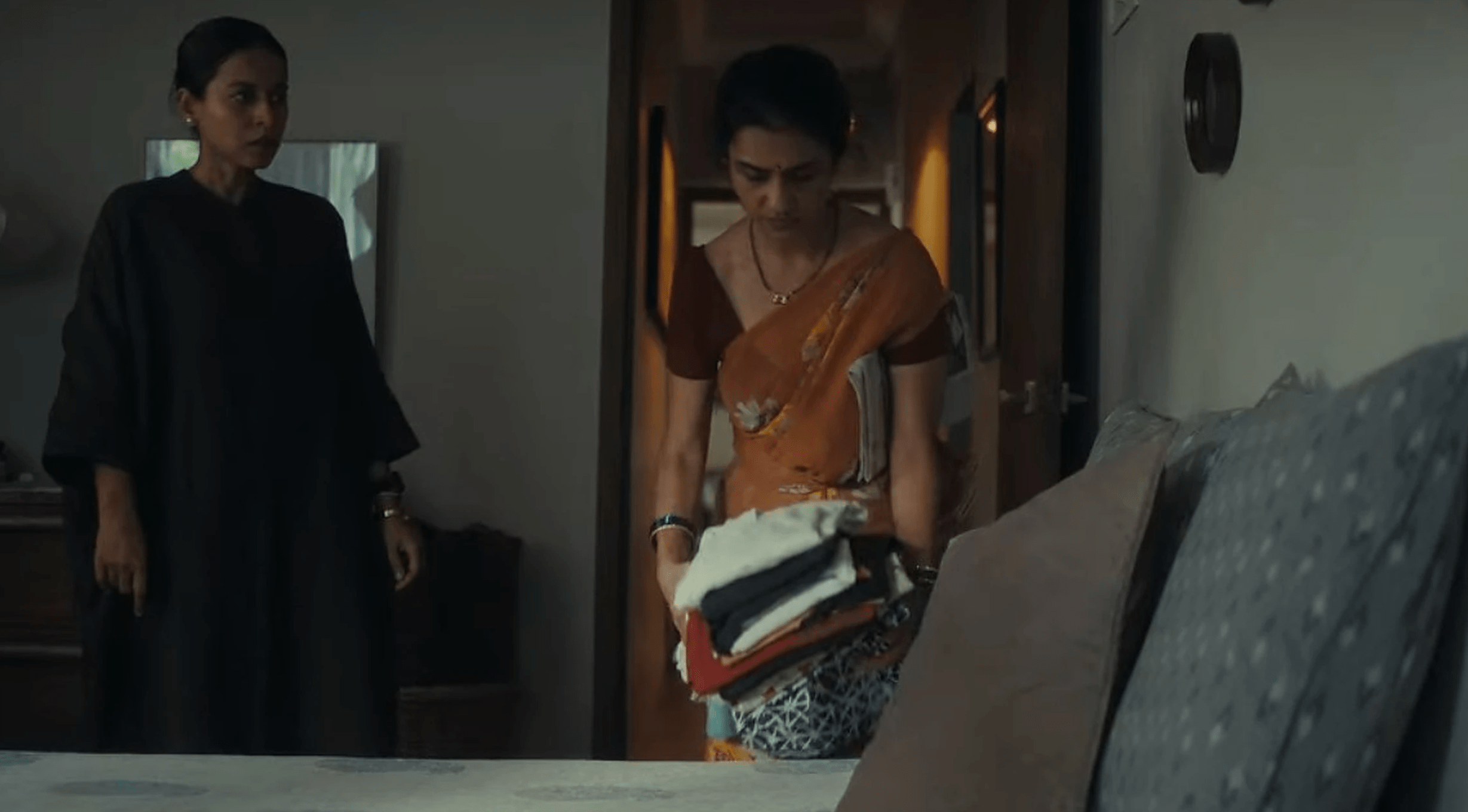

Isheeta lives alone and employs a maid Seema (played by Amruta Subhash) to keep the household chores off her plate. She calls her ‘Didi’. One afternoon Isheeta comes back and is shocked to find ‘Seema Didi’ wildly making out on her bed. Initially, she is alarmed and instinctively calls up her friend who offers her the usual advice in these circumstances – ‘Fire the maid‘.

Konkona uses the prop of a mirror excellently to show the outsider’s gaze in an act of intimacy. Voyeurism, the practice of obtaining sexual gratification from observing others, is meaningless without the outsider’s gaze and the insider’s ignorance of being a subject. The mirror becomes the focal point for Isheeta’s activities as much as it becomes a weapon for Seema later on who recognises the lust and gratification in her employer herself.

Contrary to the advice (and perhaps the expectations of viewers), Isheeta doesn’t do that and instead comes in stealthily at her own home every afternoon to watch Seema and her husband vigorously fornicating in bed. And that is what opens the proverbial Pandora’s Box for viewers. The voyeuristic pleasure that live porn provides keeps Isheeta from doing the obvious – firing the maid. Eventually, the maid too knows that she is being watched.

Konkona uses the prop of a mirror excellently to show the outsider’s gaze in an act of intimacy. Voyeurism, the practice of obtaining sexual gratification from observing others, is meaningless without the outsider’s gaze and the insider’s ignorance of being a subject. The mirror becomes the focal point for Isheeta’s activities as much as it becomes a weapon for Seema later on who recognises the lust and gratification in her employer herself.

However, things sour one day and ultimately the arrangement breaks down, but not before raising pertinent questions. One is of course the issue of female voyeurism and the delights of self-stimulation. The film also provokes a conversation or at least the thought of females as consumers of pornography which dangerously hedges feminine morality.

As an angry Seema ( who knows that the perfect arrangement has ended) blames Isheeta and calls her a “dirty woman”, the moralistic implications of a female consumer of pornography are complete. Isheeta’s friend Sameera, as also her neighbours shun her, and humiliate her. Konkona wants us to reflect on the hypocritical treatment of women as consumers of the porn industry as well as the sanctions held out to women who choose to own their sexuality and indulge in pleasures of this kind.

Statistics of pornography usage show that a whopping majority of users are males. That doesn’t have a shock value at all. Perhaps more telling is that nearly half of young women see porn watching as perfectly acceptable. Yet there are extreme reactions to women consuming the same. Konkona’s segment in the film sparks off the debate which has feminists on one side rooting for it saying that it allows the agency for a woman in deciding how to find her own kind of sexual pleasure.

This is as opposed to those who believe that no matter who watches it, it cannot be made without damaging the actors (male or female or any other ) involved in it. Perhaps that explains the liberating feeling experienced by Seema as she finds out that her employer knows about her daily dalliances in bed. It gave her a sense of agency and legitimised her stealth. Her husband, ironically, feels used and admits it as much when he protests that he was the only one who did not know.

Konkana Sen Sharma’s track also touches upon the lack of space in Mumbai’s slums which often forces couples to look for spaces where they can engage in desires. The film opens up with a shot of the Mumbai landscape in an emblematic way -tall high rises surrounded by dingy slums. Seema comes from one of these slums. A small shanty of a place is shared by the couple, their two teenage children and a parent. There is no space for lust.

Konkona smartly opens up the conversation to one of the most exploitative industries in the world that inevitably works at the cost of the participants.

Konkana Sen Sharma’s track also touches upon the lack of space in Mumbai’s slums which often forces couples to look for spaces where they can engage in desires. The film opens up with a shot of the Mumbai landscape in an emblematic way -tall high rises surrounded by dingy slums. Seema comes from one of these slums. A small shanty of a place is shared by the couple, their two teenage children and a parent. There is no space for lust.

But Isheeta’s large space, her flat that remains mostly empty offers temptation in terms of its vastness and emptiness. The couple succumbs to it and makes the most of it as long as it lasts before finding a small corner in the slum that offers its own possibilities of a hidden dalliance that is free from prying eyes and guilt. That the man in question is Seema’s husband leaves the issue minus any moral lacings that could have confused the plot and storyline.

The use of sounds and motifs (like the mirror or the calendar) to give a sense of temporal and spatial expanse and continuity is laudatory. But far more, it is Konkona’s elegance as a storyteller that stamps in her directorial authority. The empathy that she reserves for the characters she fleshes out makes viewers respond with the same. Seema’s act thus ceases to become an act of vulgarity. There is warm acceptance reserved for Isheeta too. The empathy reaches its climatic point in the end when Seema- the maid and Isheeta- the employer stand on even ground, at a vegetable seller’s stall. Both are buyers at the stall, negotiating against a common source (the vegetable man) and also each other for the prized vegetables.

It is at this moment of cinematic encounter that the women come together in an aura of acceptance, reserving empathy for the other and agreeing to another round of working with each other. Finally, the ‘keys’ change hands. The keys to the house, but also to the heart and its deep desires; keys that symbolise trustful guardianship. Clearly, Konkona Sen Sharma deserves applause for dealing out an ace yet again.

About the author(s)

Saonli Hazra is an educator and runs Words’Worth. She is a government-approved trainer for English and also a freelance writer for Times Publications. She can be reached at saonlihazra@yahoo.com.

Yet again you presented a unique perspective so beautifully ma’am.

Very well-written article!!…enjoy reading your pieces Saonli Hazra…keep writing 👍🏼

Enjoyed the episode as much Saonli. As a woman of south Asian descent , I feel conditioned to think of my own lust 😅. You have captured the essence of the short film very aptly and your article was a joy to read and mull over the angles the KSS has explored; lust, class and gender.

eye opening article and very well written!

very very well written piece and such an eye opener!

Wonderful review Shaonli! Great job! Keep up the incredible work!

What a well written review this is. Frankly after reading this I want to watch the episode again. Thank you Saonli for penning it so beautifully.

Only the keen eye can look beyond the subtle references KSS has tried to blend in. And yet again you did it & made the piece a reflection of the show.

A very comprehensive well written review, tempting one to watch the episode again!

Yet to watch LT2 but loved the layered review. Well done! Will catch up after watching LT2.