The Uniform Civil Code is a subject fraught with controversies and debate. The code proposes to scrap all religious personal laws, which govern matters relating to families such as marriage, divorce, inheritance, adoption, succession, and maintenance, and introduce one common set of civil laws that apply to all citizens in the nation.

The idea of democratic uniformity of law for everyone’s equal treatment and gender justice is a rhetoric usually employed to push its incorporation in the constitution, not only in the capacity of Directive Principles of State Policy but as a codified law.

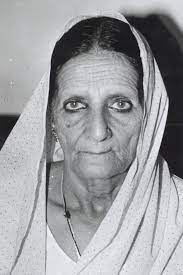

During Shah Bano, we had Hindu patriarchs fighting Muslim patriarchs where the former’s agenda of propagating the Hindutva ideology was conveniently couched as a progressive, feminist move.

Siobhan Mullally highlights this “coaching,” in her essay Feminism and Multicultural Dilemmas in India: Revisiting the Shah Bano Case:

“Bal Thackeray, a Hindu nationalist politician argued that the issue was ‘not of religion but of poisonous seeds of treacherous tendencies . . . Those who do not accept our Constitution and laws, should quit the country and go to Karachi or Lahore . . . There might be many religions in the country, but there must be one constitution and one common law applicable to all.’ The exclusionary impulse underpinning many calls for reform of MPL [Muslim Personal Law] is evident in this statement. The Hindu right was not concerned with gender equality but rather with further fuelling the politics of communalism.”

Muslim men argued for the preservation of their cultural traditions by demanding the continuation of their personal laws (which were codified during the colonial period by the British by the way) at the cost of women. Because obviously, for them, discriminatory personal laws are the only means to ensure the sustenance of a culture. This led to significant speculation regarding if multiculturalism was even compatible with feminism.

If one wants to retain the diversity of personal laws dictated by religions across India, which deal with matters regarding inheritance, marriage, divorce, maintenance, Etc, what does that imply for Indian women? However, one cannot forget that patriarchy is deeply entrenched in every institution; not only religion. Religion becomes a particularly sore topic since, in India, it makes for one of the core identities of an individual.

The rhetoric of far-right organisations and parties, namely Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), Rashtriya Swayansevak Sangh (RSS), Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP) and others, to save Muslim women from Muslim men says nothing about their concern for the autonomy of women.

A fundamentalist mindset indicates an immutable belief in the hierarchical family structure where the woman becomes an important tool to protect honour, reproduce, and enable the authority of religion. Men on both sides speak the same language and either see women as “preservers,” of culture, or their rights are used to veil (albeit, thinly) their own desire to further their set of patriarchal ideas.

However, this does not eliminate the need to scrap discriminatory personal laws. While the idea of the Uniform Civil Code appears desirable for many reasons, the drafting and implementation of the Uniform Civil Code depends on those passing the legislation. One must realise that majority voices in the parliament are Hindu voices and their version of the UCC will be awfully easy to pass.

While the Uniform Civil Code poses as a solution to end the discriminatory personal laws detrimental to women from all religions, it’s important to think about what it implies for women from minority religions. An upper-caste, upper-class Hindu woman is the most privileged woman. Further, she has the Hindu Code Bill to protect her which is a set of Hindu laws unified, codified, and modernised way back in the 1950s.

However, the notion that only the Muslim Personal Laws are discriminatory is highly erroneous. Shalaka Patil’s article demonstrates how the Hindu Succession Act, of 1956, the Hindu Marriage Act of 1955, and the now amended Indian Divorce Act, of 1869 pertaining to Christian women is or had been discriminatory in the past.

Dilip D’Souza’s article is particularly insightful and demonstrates the complexity of the web of rules that govern the civil matters of individuals from different religions and what are some fundamental problems with framing the Uniform Civil Code:

“. . .all kinds of traditions are followed in our country, and we’ve encoded those. The result is the fierce knot of rules and exceptions that we call our personal laws. So, if this knot is ever to be untied, or even sliced through, in pursuit of a Uniform Civil Code, we might ask: what can “uniform,” possibly mean here? What can it mean, when the rules for one religion are diametrically different from the rules for another and both are different from the rules for a third and fourth.”

“Just choose the “best,” rules, you say? Well, take just my second example above. Who will choose between those inheritance rules? Christians and Hindus exclude parents, and Parsis and Muslims don’t. What’s the “best,” course? Or take my first example. Parsis and Christians make no gender distinctions, Hindus and Muslims weigh agnate against cognate, but in different ways. What’s the best?”

During Shah Bano, the Supreme Court handed a decision in favour of Shah Bano by taking into consideration reinterpretations of Muslim religious texts. The traditional, dominant voices (aka patriarchal voices) in the community were provided less legitimacy in favour of the minority, revisionist reinterpretations

Living in a pluralist society, the authority of religious texts and their patriarchal interpreters that have been unanimously discriminatory against women is difficult to contest, since the same women also identify with these religious identities despite all religions’ innate incompatibility with a woman’s autonomy and choice.

Rajeswari Sunder Rajan in his essay Women Between Community and State: Some Implications of the Uniform Civil Code Debates expresses this quite aptly:

“Feminist activists may oppose state and/or community straightforwardly when there is a clear polarisation of positions between women’s interests (gender justice) and religious/state patriarchies, but in India women’s groups also have to respond to and negotiate minority claims for recognition.”

“This means that Indian feminists, because of their liberal, secular credentials (which does not exempt them from “having,” a religious identity), cannot confine their struggles to women’s interests “alone,” (if such a thing were clearly identifiable in the first instance), but are called on to be sensitive to the identity crises and threats experienced by members of minority communities, including women. This double commitment can lead to acute dilemmas for feminist understanding and to the paralysis of feminist praxis.”

In theory, it seems impossible, but in practice, the Supreme Court has demonstrated that women’s rights can be reified within religious discourses. They exemplified pragmatism without compromising on moral grounds.

During Shah Bano, the Supreme Court handed a decision in favour of Shah Bano by taking into consideration reinterpretations of Muslim religious texts. The traditional, dominant voices (aka patriarchal voices) in the community were provided less legitimacy in favour of the minority, revisionist reinterpretations. While the Supreme Court was successful in delivering its judgement, populist politics intended to bag Muslim votes clearly won out.

While the effacement of religious and cultural identities is a consequence, what is being endeavoured by the ruling party is the stripping off of other cultural or religious authorities in favour of one Hindu authority, which is extremely dangerous. The arena of laws is one realm where power is negotiated and hence, consideration of women from all backgrounds in the judicial process is important to make for an inclusive and just legal system. We don’t need a Uniform Civil Code for that.

In the push for the Uniform Civil Code, women’s rights, as usual, are relegated to the back burner. Religious leaders with fundamentalist orientations and their claims continue to hold precedence.

About the author(s)

Shakti (she/her) is an English major and an aspiring tea sommelier. She loves reading poetry and drama and can be found with a Kindle most time. She intends to become a teacher of humanities and is passionate about literature, films, politics, and history. In her free time, she has been caught watching cringe content, however, she fervently denies these claims.