In a major chronicle of emperor Shah Jahan’s reign, the Shahjahannama, Inayat Zaidi refers to a conniving scheme to kill Prince Aurangzeb. Immediately after Aurangzeb’s victory over Dara Shukoh at Samugarh, Shah Jahan planned to lure Aurangzeb into the confines of the harem at Agra Fort where armed Tartar female slaves would slay the mighty prince. In his historical travelogue, Bernier narrates something similar.

In his version, Princess Jahanara Begum, an ardent supporter of Dara, hatched a plot to cajole her brother into the zenana. Several large and robust Tartar women would then fall upon him with arms. However, a sharp-witted Aurangzeb refused to fall for any such ploy. Whether or not this was merely a rumour retold by the above authors, it is nevertheless compelling as it brings into light an important group of women who assumed a physically protective role in the Mughal harem: the Urdubegis.

The guardian presence of Urdubegis can be traced back to the time of Babur and his kinswomen who descended into the Indian plains. Historical sources, unfortunately, do not offer any cohesive account of Urdubegis. The mention of little instances in various chronicles helps us compile a broad narrative about their unique role, which is quite important in multiple ways. One, it brings a new perspective into the otherwise masculinised idea of aggression and defence, relegating women to limited roles.

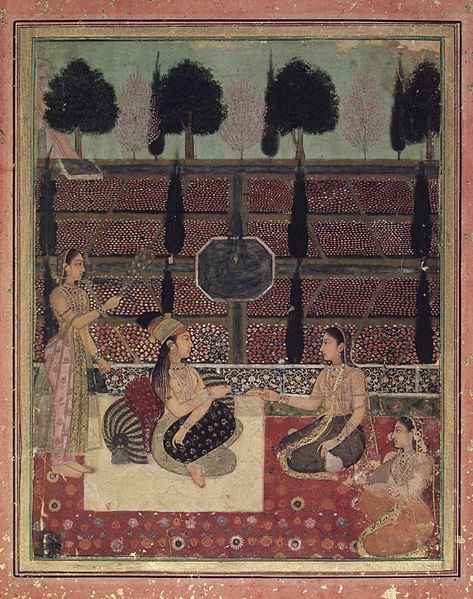

Secondly, Urdubegis complicate our monochromatic imaginations regarding the harem, bearing testimony to the diversity of women in Mughal harems in terms of their functions, influence, race, culture, artistic abilities, Etc. They also attest to how notions of femininity were differently formulated, perceived and employed depending on the historical situation, race and even practical requirements.

Who were the Urdubegis?

In the Mughal literary magnum opus, the Akbarnama, Abul Fazl writes that the “inside of the harem is guarded by sober and active women; the most trustworthy of them are placed about the apartments of the majesty.” While Abul Fazl is reluctant to offer more details on the corps of Mughal female guards, earlier or contemporary works offer a clearer picture.

Nizam al-Din Ahmed who wrote Tabaqat-i-Akbari mentions that Sultan Ghiyath Shah (1469-1500), allegedly possessed sixteen thousand slave girls, and five hundred of them, who were distinguished for their genius were trained in various learnings, including wrestling. He then makes a notable reference to the armed female attendants of Ghiyath Shah:

“He had five hundred Abyssinian slave girls dressed in male attire, and arming them with swords and shields gave them the name of the Habiwash band. He also called five hundred Turki slave girls in the Turki dress as the Mughal band.”

Muhammed Qasim Firishta later writes in Tarikh-i-Firishta about armed female retainers in more detail:

“Five hundred beautiful young Turki females in men’s clothes, and uniformly clad, armed with bows and arrows, stood on his right hand and were called the Turki guard. On his left were five hundred Abyssinian females also dressed uniformly, armed with firearms.”

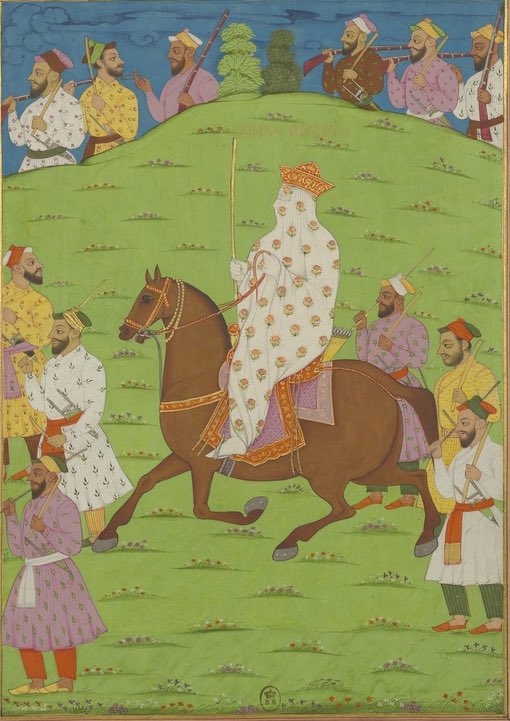

Scholar Gavin R. G. Hambly refers to Urdubegis as ‘a kind of female Mamluks,’ of diverse ethnic backgrounds, indicating they were sufficiently strong to guard the emperor and his household, similar to the characteristic slave warriors of medieval Islamic rule. They were recruited from faraway regions, possibly due to security concerns. They guarded the emperor while in the harem, and protected his women both in the harem and in their peregrinations to hunt, play games, visit shrines and in long-distance campaigns.

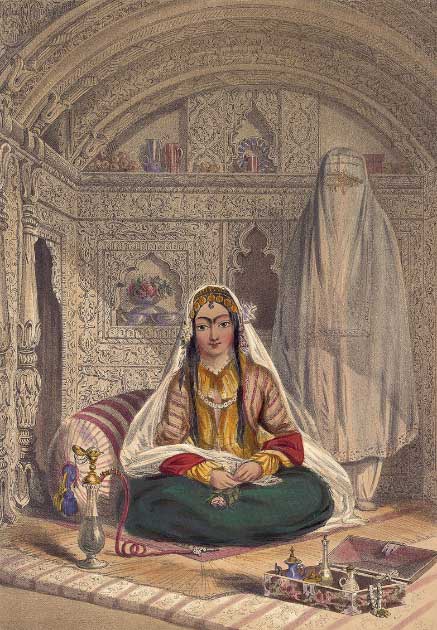

Manucci, the Italian traveller specifically notes their absence of veils. According to him, the doors of the harem were guarded by women who were mostly native to Kashmir and they never veil themselves to anybody. While the shedding of the veil was vital for their defensive responsibilities, such a sartorial difference was also enabled by the ethnic differences of Urdubegis, largely purchased from Habshi, Tartar, Kashmiri and Turki tribes.

Their physical prowess is also essentialised by their role as palanquin bearers for short distances. For entering and leaving the private quarters, female servants replaced men in carrying the travel conveyances. An English account of Awadh from the early 19th century mentions that the King’s mother’s immense chandūl (largest palanquin) was carried by 20 powerful male bearers and surrounded by strong female bearers whose duty is to carry the conveyance into the private apartments.

A similar class of female bearers of Awadh finds mention in William Knighton’s “The Private Life of an Eastern King.” According to him, the female bearers were militarily disciplined and their head was a great “masculine,” woman who was a favourite of the king.

Distinguished with highly skilled management of the bow and arrow and the short dagger, Manucci, the Italian traveller specifically notes their absence of veils. According to him, the doors of the harem were guarded by women who were mostly native to Kashmir and they never veil themselves to anybody. While the shedding of the veil was vital for their defensive responsibilities, such a sartorial difference was also enabled by the ethnic differences of Urdubegis, largely purchased from Habshi, Tartar, Kashmiri and Turki tribes. They mainly wore modified women’s clothing or male attire for convenience.

Female guards in ancient India

An institution of armed women like the Urdubegis to protect the emperor and his kinswomen is not a uniquely medieval phenomenon. For instance, Indica by Megasthenes is considered one of the most extant accounts of female bodyguards of ancient India. Megasthenes notes that the care of the king’s body is committed to women who were purchased from their fathers.

In another instance, he writes that in hunting expeditions, the king is surrounded by a circle of women and outside of them is a circle of male spear bearers. Any person who passes inside the circle of women is killed. While the king hunts from a platform, two or three women stand beside him. The women also hunt, sitting on chariots, horses and elephants.

Reflecting on the same, Kautilya writes in the Arthaśāstra that the king should be surrounded by female guards bearing bows (strīgaṇair dhanvibhiḥ) in his bed chamber at night. In light of this evidence, Walter. D. Penrose Jr argues that South Asian monarchs were guarded by women from at least the Mauryan period until the 19th century.

In ancient Indian and Achaemenid Persian cultures, the women bodyguards also hunted with the king. As Penrose notes, actual and fictional images of women as intimate bodyguards are visible in other sources like Vatsyayana’s Kama Sutra, ancient Buddhist literature and iconography, Kalidasa’s dramatic prose, Banabhatta’s mythological poetry, Chinese, Arab and European travel accounts Etc.

Why are Urdubegis unexplored?

One can argue that the invisibility of this community of women in popular memory, historical literature and the current-day representations of the harem in popular culture is largely due to the failure to comprehend the diversities of the functional roles of women in their quarters and the larger political stage.

According to Gavin. R. G. Hambly, “European writers of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, whether bona fide travellers in the Islamic world or stay-at-homes with imaginations run riot, saw the harem or zenana as a quintessential place of incarceration, a symbol of brutal servitude and unrestrained lust.” The women’s quarters in the Ottoman Sultan’s palace, introduced to English readers by Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, Thomas Allom, Etc became the prototype of a Muslim harem through which harem life was generally looked at.

In contrast to this European imagination, Hambly states that “the zenana was not a confined space inhabited exclusively by wives and concubines, but rather consisted of a diverse community of women of varying ages interacting with each other in many different ways and at many different levels.” This multitude of women was to be managed by a carefully devised system that required the employment of active and intelligent women under various offices. Thus, there were Daroghas (matron), Mahaldar (chief lady officer), Tehwildar (accounts officer and cashier), Mushrifs (superintendents) and of course, the Urdubegis. As scholars have noted, there were female officers in the harem for every male administrative counterpart.

One can argue that the invisibility of this community of women in popular memory, historical literature and the current-day representations of the harem in popular culture is largely due to the failure to comprehend the diversities of the functional roles of women in their quarters and the larger political stage.

A second reason for the forgotten status of Urdubegis is the lack of enough information on female affairs in contemporary chronicles and other literature of the time. Mostly authored by men, these primary sources have a palpable reticence to elaborate upon female royal establishments. Thus, Urdubegis appear only as quickly dissipating images in the larger descriptions of magnificent events or dramatic royal encounters, and never in their own right.

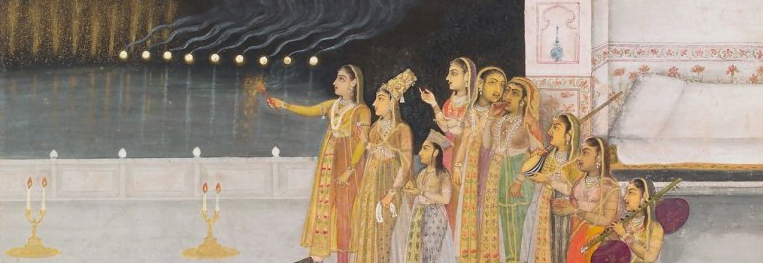

Accordingly, we can see Urdubegis, who were ‘Tartars and Kachmeyres,’ ‘fantastically attired and riding handsome pad horses,’ surrounding princess Raushanara Begum who is sitting atop an elephant in an elaborate procession of 66 elephants leaving Delhi, as recorded by an impressed Francois Bernier in the seventeenth century. Khafi Khan, the Mughal historian notes that in 1719 when Farrukh Siyar took refuge in the Harem and his opponents tried to enter it, “the women, the Abyssinians and the Turks, all prepared to fight.“

Life of Bibi Fatima

The only Urdubegi whose biographical information is available to us is Bibi Fatima, mostly mentioned in Humayun Nama, written by Gulbadan Begum. As Khadija Tauseef opines, “Perhaps Bibi Fatima was mentioned because a woman wrote the biography and found the contributions of the female guard worthy of remembrance.”

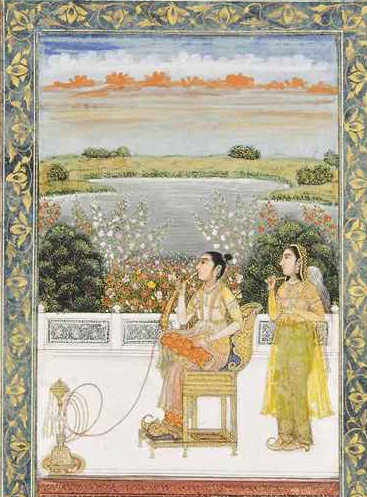

Originally a wet nurse to Emperor Humayun, Bibi Fatima worked for the emperor his whole life and then served under Akbar. She was the chief Urdubegi of the zenana in Humayun’s reign and probably held other roles such as superintendent. Presumably a Chaghtai Turk by origin, Gulbadan refers to Fatima as Sultan, suggesting the honorific position she held during Akbar’s reign when the memoir was written. Bibi Fatima played an inevitable role in taking care of the sick emperor till he became convalescent during the long peripatetic exile of the royal family during Humayun’s reign.

A contemporary observer Bayazid Bayat mentions that during this crisis, “Bibi Fatima, “chief Urdubegi of the palace, left nothing undone so far as attendance on his majesty was needed.” Since the danger of an assassination attempt lurked around the emperor, “Humayun’s safety must-have in part depended upon her vigilance,” according to Bayazid. She was also present in the diplomatic mission despatched to Badakshan by Humayun and was the first to realise and report the secret administrative intentions of the Badakshanis to her fellow men.

Another significant episode that mentions Bibi Fatima is when she sought help from Emperor Akbar to protect her daughter from domestic violence. Her daughter Zuhra was married to Hamida’s (Akbar’s mother) brother. Akbar promised Fatima that he would pay a visit to their house and warn him to mend his ways. However, seeing Akbar’s imperial officers approach him to announce the emperor’s arrival, Zuhra’s husband stabbed her and flung the weapon toward the oncoming servants. He was then taken to the state prison where he died insane. According to Gavin Hambly, one source notes that the news was broken to Bibi Fatima personally by Akbar, who then approved the emperor’s actions.

Mentioned briefly in Humayun nama and with scattered references in other sources, Bibi Fatima’s concise account is a manifestation of the multifaceted roles and experiences of women in royal circles. She took up multiple roles of prominence in the harem, stayed close to the emperor himself, undertook negotiatory roles when required, rose in importance with sheer loyalty and sincerity of work, formed marital relations with the royal family and even received personal assurance and attendance from the emperor during times of distress.

Decline of Urdubegis

The fall of Urdubegis possibly happened with the defeat of the ultimate Mughal emperor, Bahadur Shah Zafar which marked the culmination of the empire. The accompanied end of the harem as a personal and political institution rendered the function of Urdubegis pointless. One of the last references to female guards is Valentine Blacker’s memoir of the British army, which describes a corps of female sepoys who guarded the zenana of the Nizam of Hyderabad in the late 18th century.

Royal histories and their scholarly reconstructions marginalised women’s role in overarching political affairs causing the protective service of Urdubegis to be cloaked in obscurity. Recently, the functions of royal women and the institution of the harem as a politically and culturally happening place are being reclaimed as important avenues of research. This offers us new ways of looking at the nature of medieval states. Such a redefined scenario of scholarship adds much significance and might to the arm-wielding, horse-riding image of vigorous Urdubegis who guarded the emperor and the royal women with valour.

References:

- Armed Women Retainers in the Zenanas of Indo- Muslim Rulers: The Case Of Bibi Fatima (ed.) Women in the Medieval Islamic World by Gavin. R. G. Hambly

- The Mughal Harem by K. S. Lal

- Urdubegis: The Forgotten Female Fighters of the Mughal Empire by Khadija Tauseef

- Post Colonial Amazons: Female Masculinity and Courage in Ancient

- Greek and Sanscrit Literature by Walter Duvall Penrose Jr

- Storia do Mogor or Mogul India: 1653-1708 by Niccolao Manucci, translated by William Irvine

- Travels in the Mogul Empire: A.D. 1656-1668 by Francois Bernier, translated by Archibald Constable