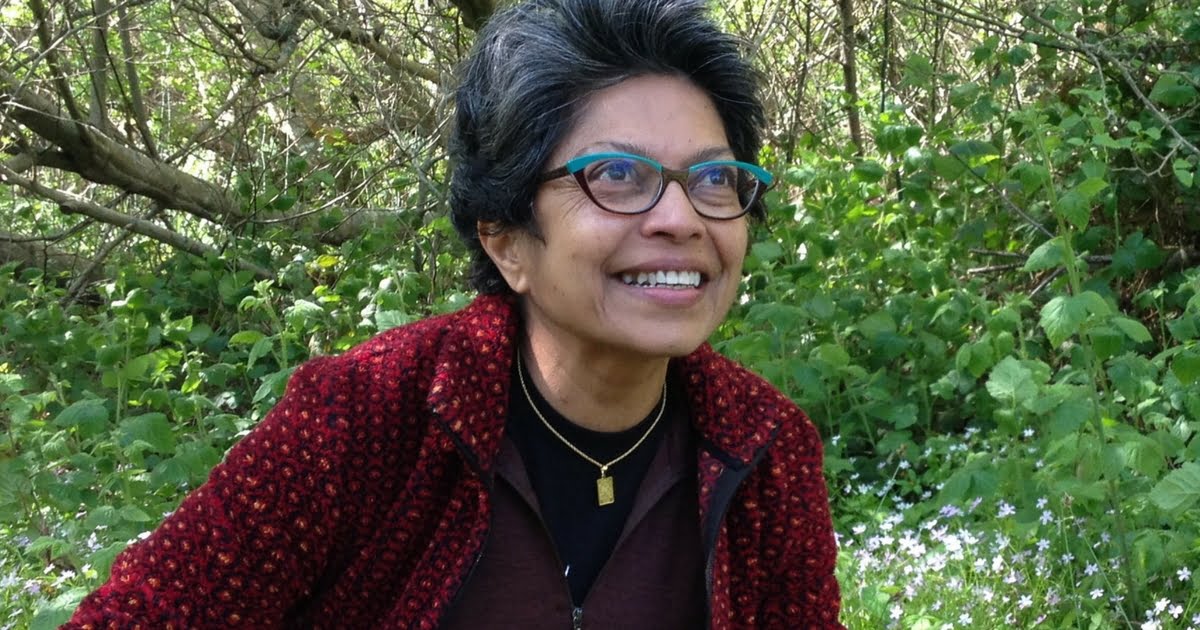

In her short spanning career of 32 years professor and scholar Saba Mahmood was resilient with the politics of category on gender, especially for women, taking a stand for their rights; born in 1962 in Quetta Pakistan, she moved to Seattle to study at the University of Washington.

In 1998 Saba Mahmood received her PhD in anthropology from Stanford University thereafter establishing herself as one of the most influential poststructuralist and post-colonial anthropologists. Her scholarly works on political theory and anthropology focused on women, especially from the Muslim-majority societies of South Asia and the Middle East.

Her work like The Politics of Piety: The Islamic Revival and the Feminist Subject echoed her take on politics of category and displayed her liberal conviction on women’s rights. Politics of Piety is a coalescence of her rich ethnographic observations of women’s share amid the Islamic revival movement in Egypt with correspondence to the global revival taking place in the Muslim world for resurgence and practice and public expression of Islam in a wider spectrum.

Politics of Piety is theoretically encouraged work of Michel Foucault and Talal Asad – an anthropologist. In the book Saba Mahmood takes a deeper dive into the notion of feminist scholars and their effective agencies, the one located within the political and moral autonomy of the subject; and how these agencies have brought to bear upon the study of women in religious traditions like Islam.

Mahmood goes on to challenge this notion and emphasises that the agencies should reflect upon relating the embodied experiences and the means forming the subject for these experiences and asks ‘How do we conceive of individual freedom in a context where the distinction between the subject’s own desires and socially prescribed performances cannot be easily presumed, and where submission to certain forms of (external) authority is a condition for achieving the subject’s potentiality?’

She emphasised that the changes in the Muslim community, in the women majorly were entirely ethical action and moral, guided by the religious texts, rather than arousing out of the liberal notion of freedom of an individual. She illustrated the importance of ethics and morals in the transformation of the state with structures getting dissolved within, which she believed to be promising compared to the rights of the individuals.

In her work, she valiantly talked about how the political and moral autonomy, in an intellectual rather semi-intellectual atmosphere, led by the West and Western liberalism critiques dubbed the clash of civilisation as ‘radical,’ denying the liberal notion of freedom, which also dismissed the complex life- worlds of religion as a subject. She carefully examined the notion of ‘rights‘ on the basis of individual freedom and autonomy, which often reflects in her work.

It was during this time that the ‘mosque movement,’ saw unprecedented participation of women in the male-dominated area like the mosque itself, her theories pointed out that this rise and desire was never informed because of freedom, equality or autonomy but rather were guided by the religious text, which she elaborated in her book through an example of ‘Hajjah Fizah,’ the lady here presents a powerful rooted justification for the presence of women in the mosque, for these were based on the holy scripture’s exegetical tradition and the political position of women in the legal traditions of the religion.

Saba Mahmood, inquired into the key questions back then which are relevant even today, on how the issues of historical and cultural specificity inform both the analytics and politics of any feminist project thereafter resulting in serious attempts at integrating issues of sexual, racial, class and national differences within the feminist theory, leaving the question of religious difference unexplored.

She examined the vexed relationship between feminism and religious traditions, specifically in Islam, where the discussion is most manifested; which she argued was because of the ‘contentious relationship that Islamic societies have had with what has come to be called the West.’

Her theories talked about the contemporary challenges Islamic movements posed to secular and liberal policies of which Feminism has been an integral part, she was of the opinion that ‘inimical to their own interest and agenda where women form an active support to the movement, at a historical moment when more emancipatory possibilities would appear to be available to women, raises a fresh dilemma for the feminists.’

In her essay “Feminist Theory, Embodiment and the Docile Agent: Some Reflections on the Egyptian Islamic Revival,” she explored some of the conceptual challenges that women’s participation in the Islamic movement posed to feminist theorists and gender analysts through an ethnographic point of view. Here she also talked about the urban women’s mosque movement as a part of a larger Islamic revival in Cairo, Egypt, where she gives an account of women coming from vivid socioeconomic backgrounds providing lessons to each other on Islamic studies, its scriptures, social practices, therefore, cultivating ideas of virtuous self.

It is commendable how Saba Mahmood criticised ‘the West,’ notion considering her presence from a prominent and most liberal campuses in America; from a career as a Left Liberal activist in Pakistan during the 1970s, where the ‘Islamisation,’ was propped up and consolidated into neo-imperialist designs as a part of US foreign policy.

Later on, in after years she went on to talk about the limits of political secularism and blasphemy, a collection of essays Is Critique Secular? in collaboration with Talal Asad, Judith Butler, and Wendy Brown. Mahmood argued the normative conceptions of European ideas of liberty privileges and belief in a religion and its consciences on practices and ritual of it.

In her intellectual endeavours, Mahmood has been anthropologically and theoretically honest in her thoughts and words; within her feminist theory, she enlightens her readers that it is not always that a woman is mindlessly obedient or her liberty evokes her action, her distinct hermeneutical approach as well as the religious culture too has a prominent role to play in her redefining her ideas for herself and community.

About the author(s)

Anupama intends to be an artist in neutral, aka a dabbler- cum-learner. Her interests lie in music, nature, stories transcending cultural boundaries, human welfare, etc. When she is not around she can be found strolling along the ghats of Varanasi. To add she has a lab- named Miley.