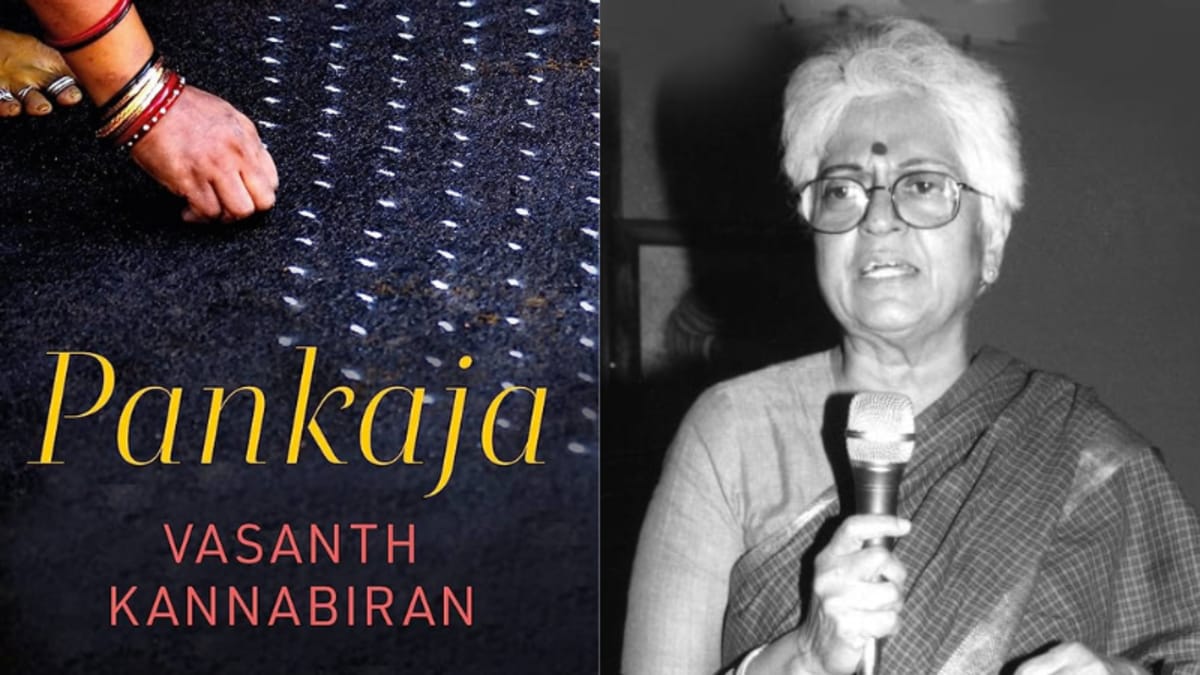

Written by Vasanth Kannabiran, Pankaja brings together stories of many upper-caste women—wives, widows, and whores—in South India in the early 20th century. Kannabiran states in the book that these stories were passed down to her in bits and pieces from her grandmothers and aunts while some of them were witnessed by her.

The novel explores various aspects of being an unfortunate widow and a chaste wife. It shows the ways in which women exercised their sexuality during that time. At the centre of it all, lies one truth: Marriage, contrary to the popular notion, neither provides security nor happiness. Kannabiran has recorded her conversations with women on marriage and widowhood in her previous non-fiction, A Grief to Bury: Memories of Love, Work and Loss. It is no surprise that these themes recur in her 2022 debut fiction.

The titular character Pankaja grows up in a house of respected widows. These widows abandon their jewellery and adorn white sarees without a blouse. However, they exercise a certain amount on independent agency by refusing to disfigure themselves by shaving their hair.

Widows who survived, widows who suffered

In India, it is a known notion that Hindu brides are associated with good luck and Lakshmi. As Kannabiran begins her “old wives’ tale” with the description of widowhood one cannot help but wonder — why does the good luck go away with the death of the husband and is replaced with misfortune? A widow’s presence is seen as an unwanted shadow in the lives of unmarried or married women and pregnant women. If they come too close, they might contaminate the good fortune of these women with their supposed ill-luck.

The widows in Pankaja are not shown as helpless. Pankaja’s mother owns farming land and also has tenants in Madras. Her elder sister, Pattamma, who has been widowed at an early age explores her sexuality at her own will, having lovers that people might frown upon but cannot question. Pattamma builds her personality by making her life choices despite the fate of widowhood. She builds her interest in politics by listening to the radio and entertaining intellectual guests who discuss the national freedom struggle at large. Despite her misfortunes, she neither feels the need to cover her shoulder or her back that remains bare in her saree. Nor does she allow society to decide her lifestyle after getting away from a short-lived mockery of a marriage.

Vis-a-vis Pattamma, there is the character of Bhagya—an educated widow who gets a job but doesn’t earn the respect and security that society avails to married women. She is miserable and longs for marital bliss even if she has to be the second wife of a man. In narrating such experiences, we see Pankaja addressing two sects of widows in the following lines:

“There were the ones who suffered and those who survived. The ones who survived, eloped if they were lucky or stubbornly lived lives of dignity like her sister Pattamma. Inspired by Periyar, she never bowed her head, and lived freely. Then there were the ones like Bhagya. They managed to get an education but lacked the strength or character to live alone or to find a single man who would be glad to marry them.”

The fragility of marital bliss

Having grown up in the shadow of widowhood, all Pankaja ever wished for was a married life. Despite her husband’s occasional debauchery that’s excused with a dismissive ‘men will be men’, she manages to have a happy married life with him, raising two children together. The culture at that time allowed men to have whores outside the house whom they cannot bring inside, keeping the respect and dignity of the wife intact.

Pankaja is baffled by a relative, Kannamma, who leaves a respectable life and family to live with a Mridangam player who happens to be a Pariah. Kannamma lived openly in a hut in the slum. Her relatives were ashamed to see her live so freely.

“Without her music, she [Kannamma] would have been trapped in a loveless marriage permanently. But her music, the fact that she could face the public and earn both money and applause, had set her free from that web. A web of deceit. And she lived with her head held high while her critics cowered in shame. She had openly exposed the fragility of wifely virtue.”

Pankaja by Vasanth Kannabirab

“Without her music, she [Kannamma] would have been trapped in a loveless marriage permanently. But her music, the fact that she could face the public and earn both money and applause, had set her free from that web. A web of deceit. And she lived with her head held high while her critics cowered in shame. She had openly exposed the fragility of wifely virtue.”

Later, when Bhagya enters Pankaja’s life as her husband’s second wife, Pankaja is filled with rage and walks out of her husband’s house with her children. Despite having stepped up for herself, Pankaja remains a victim of patriarchy in such ways that her sons blame her for ruining the family. Though she left in order to preserve her self-respect, she still kept expecting her husband to realise his mistake and come to her doors seeking forgiveness.

The question here arises, what are the criteria for women to feel happy and secure in a marriage? Bhagya might have married Pankaja’s husband, but she lives a miserable life because her husband changes in the absence of Pankaja. He had assumed that Pankaja would merely be upset. The thought that she might dare to leave him had not even occurred to him.

It is only with his death in the end that Pankaja feels truly free, devoid of patriarchal expectations. By then, she had come to understand that irrespective of social circumstances, an individual has the agency to choose how they want to live their lives.

Women and bigamy

Bigamy was outlawed in India in 1955. Before that, it was acceptable for upper-caste Hindu men to have a wife for safekeeping (marked by the mangal sutra). Because they were safe, the men could marry an educated widow to make a status statement. However, younger men hesitated to marry widows fearing that they might contaminate their lives with their misfortune.

Bigamy was outlawed in India in 1955. Before that, it was acceptable for upper-caste Hindu men to have a wife for safekeeping (marked by the mangal sutra). Because they were safe, the men could marry an educated widow to make a status statement. However, younger men hesitated to marry widows fearing that they might contaminate their lives with their misfortune.

The first wives of many men slithered to a corner of the house instead of rebelling in the fear of losing status and property that should ideally be inherited by their children. In fact, Kannabiran narrates the rebellion against outlawing bigamy in the following lines:

“When the law prohibiting bigamy was to be passed, large numbers of married women protested because they were afraid that they would be divorced and left without status or rights, and children disinherited. Women were so badly off that they felt it was far better to slave away in a corner of their husband’s house, swallowing the humiliation and holding poison in their throats for the sake of their children.”

Pankaja is a series of interlinked stories of various characters that might seem cumbersome initially. It tells the stories of generations together, merging the past, present, and future. Death overshadows everyone’s life. Occasionally matters of sexuality are narrated in ways that convey the truth to readers but the characters in the story are left blinded. The focus remains on upper-caste Hindu women and hence, a certain amount of individual agency is shown in ways that might not be available to people from oppressed castes.

These stories invite and engage the reader in contemplation while busting the myths of marital bliss and showcasing the misfortunes of widowhood that upper-caste Hindu women lived with during the early 20th century.

A little known challenging book has been reviewed in a nice manner. The reviewer has discussed all aspects of status of women in south India as portrayed in the book. The status of widows is not different pan India even today. Feminism in India is doing a good job to do impart real justice to the women in the society. Kudos.