To title a book after the alternatively feared and revered Bandit Queen of India is an audacious act. On the one hand, it raises eyebrows, demanding the audience to straighten up and take notice; on the other hand, invoking Phoolan Devi’s name also carries with it the burden of living up to her name, her fame, and her legend. This is a tough balancing act.

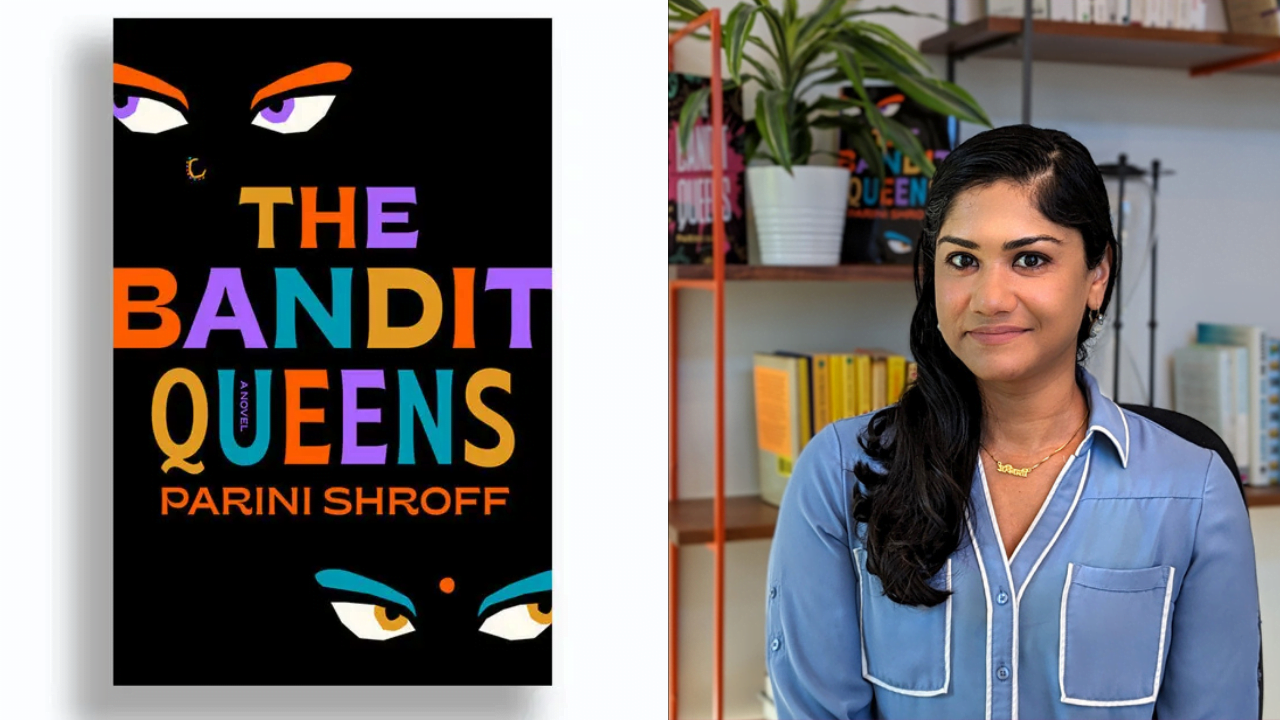

Parini Shroff’s debut novel, The Bandit Queens, already longlisted for the 2023 Women’s Prize In Fiction walks this line somewhat cognisantly though not always unfalteringly.

The Bandit Queens is set in an unnamed village in Gujarat, some distance away from the larger town of Kohra. The story unfolds through the eyes of Geeta, a woman in her mid-thirties who was mysteriously abandoned by her husband a couple of years ago which has made her the social pariah of her village. Not only is she isolated and excluded, she is feared by the town elders and children alike because of the rumours flying around of her hand in her husband’s inexplicable disappearance. She is a scorned woman, a sorceress who can turn sweets into gobar at will, or at least that’s what the children in her village tell.

Geeta runs a small business selling mangalsutras or wedding chains which she finances through a small microfinance group that she is a part of along with four other women — the long-suffering homemaker Farah and childhood friend turned nemesis, Saloni among them. The novel traces their journey from downtrodden housewives to a band of fearless vigilantes, built in the mould of Phoolan Devi herself.

Social commentary through dark humour

Though the material is heavy and rather morose, Shroff infuses her story with levity. All of the characters, barring maybe Geeta herself and her love interest Karem, are made intentionally larger-than-life and melodramatic. They speak loudly, often in a crude tongue and make jokes at inopportune moments. Their energy can be compared to that of the characters seen in Indian soaps. They bring much-needed comic relief to the otherwise quite despondent story.

A character like Bada Bhai, the big bad villain who is involved in illegally selling liquor is in fact laughably inept at his job as a menacingly mad don. In fact, he is revealed to be a less fierce bootlegger, a more small-town wannabe don as the story progresses.

At other times, however, the humour doesn’t land well. Priya, one of the women in the loan group, does not have one original thing to say for most of the book. Like a parrot, she mimics whatever her twin sister suggests with the added injunction of ‘like so,’ (emphasis on so): “like so rewarding,” “like so tasting,” “like so dramatic.”

Priya becomes a caricature of a caricature, a character without much personality or substance whose only trick is a slight play on words. Not to mention, the particular addendum of ‘like so,’ and the cadence and rhythm with which she says the words are distinctly American which detracts from the believability of the dialogue entirely.

Though it makes consistent use of the dark humour spouted by its melodramatic characters, The Bandit Queens also delves into a wide range of societal issues. It tries to address everything from the domestic oppression that women (particularly homemakers) suffer to the corrupt law enforcement system, from the casteism that plagues small-town India to sexual assault.

Some of the social commentary is effective. For example, Geeta’s love-hate relationship with her estranged husband, Ramesh, is entirely believable. This was a man that showed her some small kindness when they first met, a man who she was conditioned to love and respect above anyone else. Her going back to being his wife despite all the horrific mental and physical violence that he inflicted on her is at once disheartening yet understandable.

Geeta has been conditioned to look the other way when he errs, to say ‘You’re right. I’m wrong. I’m sorry,’ even when he is at fault. Even for someone as self-aware as Geeta, these are not ways of thinking that can be dismantled on a whim.

Some other parts of the social commentary however feel a tad forced. Shroff’s only Dalit main character is a woman named Khushi. She weaves in and out of the story, not quite part of the main microloan group. We are told she is from the Dom caste, that she disposes of dead bodies and that she has two sons and an adopted daughter. The narrative reminds us time and again that Khushi has worked her way up to the top, we are told that she has a two-storeyed house bigger than Geeta’s, and we know that she is better off than almost all the other Dalit persons in the village.

Yet it is never made clear how exactly she gets to the top. After all, if working hard was the only requirement surely all the Dalits in the village would be better off. Moreover, her presence in the story seems important only in order to further Geeta’s own arc. Geeta goes to Khushi’s house to convince her to run for the Panchayat. Geeta talks about the importance of giving the marginalised a voice, yet the only reason why she wants Khushi in the council is so she can swing a majority vote when a request for permanent separation from her husband is put forward in front of the council.

The apparent Americanness of The Bandit Queens

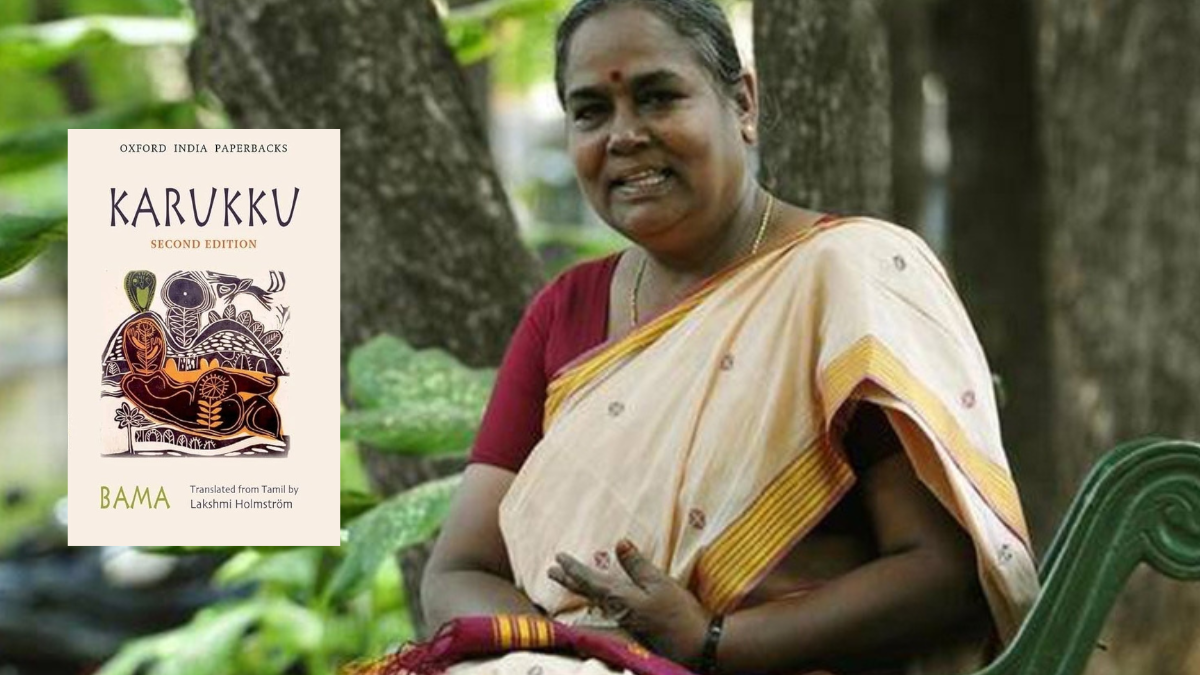

In her book The Perishable Empire, Meenakshi Mukherjee talks about the anxiety of Indianness faced by an Indian writer who writes in English. English feels less Indian and more foreign when compared to native languages such as Hindi, Urdu, Tamil or Bengali. And so, when writing Indian stories in a language that is decidedly un-Indian, writers often try to make their stories appear more overtly Indian. This is sometimes done through a universally acknowledged shorthand that serves to enhance the story’s apparent “Indianness.”

This story is particularly peculiar because not only is it set in rural India and written in English, it is written by an Indian immigrant whose experience of India differs completely from someone born and brought up in this setting. The dialogue between the characters has a distinctly American twang.

In The Bandit Queens, Shroff makes use of recurring Hindi proverbs translated into English in an effort to make the text seem more rooted in the reality of its characters — ‘dal mein kuch kala,’ becomes ‘black in the lentils,’ ‘naam mein mitti milana,’ becomes ‘name mixed with dirt.’

The age-old sayings are strangely stilted when translated into English. Moreover, these sayings are repeated time and again throughout the course of the novel, as if to remind us that the characters are still speaking in Gujarati/Hindi.

This story is particularly peculiar because not only is it set in rural India and written in English, it is written by an Indian immigrant whose experience of India differs completely from someone born and brought up in this setting. The dialogue between the characters has a distinctly American twang. For example, Farah has the following dialogue in the third chapter:

Oh. Right, right.” Farah cleared her throat. “But what I meant was, like, there’s regular hate, right? Which is really just dislike. Kinda like how you don’t like…well, anyone. But that dislike disappears when you’re not looking at them, ’cause you got other things going on. But you and Saloni hate-hate each other.

The way Farah talks resembles what one might hear from a character in a contemporary American television drama. Geeta too exclaims phrases such as ‘Hell yeah,’ that do not have any possible equivalents in her own language of Gujarati. The way of talking that the characters adopt takes away from the small-town setting in that the narrative is supposed to take place.

Phoolan Devi in The Bandit Queens

In The Bandit Queens, Geeta is an ardent admirer of Phoolan Devi. At several points in the novel, her situations remind her of Phoolan’s story which gives her the strength to power through her obstacles against all odds.

However the integration of Phoolan’s story into the narrative is not always smooth; in the middle of a highly charged, tense scene Geeta would go on a mental monologue that summarises a similar event in Phoolan’s life. The way her story is enfolded into the narrative feels forced and at times unnecessary.

Apart from this, Geeta sometimes goes on mental monologues about other popular myths too. When Diwali is at hand, she talks about Sita’s mistreatment in the hands of Ram and at another point in the story she talks about the Indian folklore of the churel.

While the inclusion of Sita’s story weighs down the pacing of the otherwise fast-paced text, the churel has the opposite effect. Geeta has been repeatedly referred to as churel for most of the story, in the end reclaiming the title of churel as one of power rather than shame proves cathartic for both Geeta as well as the reader.

About the author(s)

Keerthana (she/her) is a third-year English Literature student at St. Stephen’s College, Delhi University. She is interested in analysing art and pop culture through feminist and other sociocultural theories. She enjoys literature, music, films and the occasional cricket match.